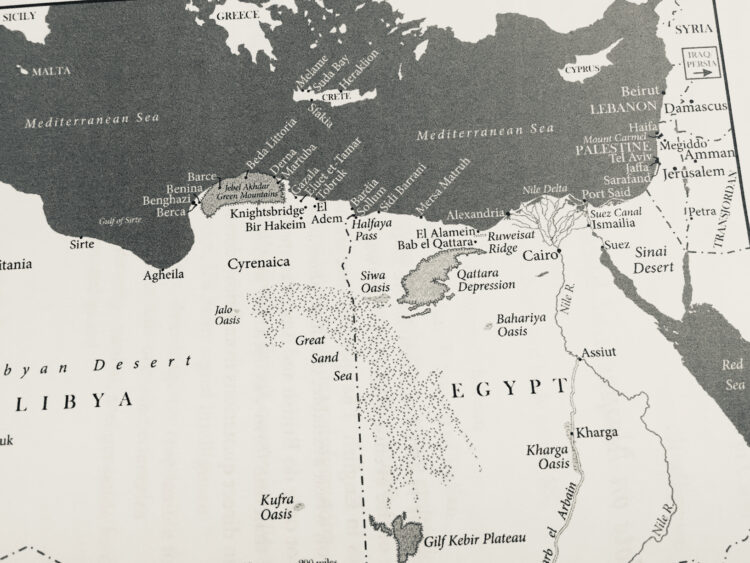

As Germany conquered one Western European country after another in 1940, Britain and Italy fought ferocious battles in Libya and Egypt, while the Italian Air Force bombed Tel Aviv and Haifa. Germany intervened in the desert war in 1941, dispatching General Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps to assist its Italian ally, which had begin losing ground.

Rommel’s troops stormed into Egypt, heading toward Alexandria, Cairo, the Suez Canal, Palestine and beyond. In Iraq — a League of Nations mandate held by Britain — pro-German politicians staged a coup, which spawned a pogrom in Baghdad. Lebanon and Syria had already been wrested from France by the Vichy regime, which was aligned with Germany.

Britain’s colonial empire in the Middle East appeared to be in peril.

Reacting to these catastrophic setbacks, the United States and Britain invaded Morocco and Algeria. Germany, in turn, occupied Tunisia, threatening its venerable Jewish community.

All the while, a corps of dedicated British cryptographers in Bletchley Park worked furiously to decipher highly classified messages from Enigma, the devilishly complex German military code.

Gershom Gorenberg, an Israeli journalist, sizes up this momentous chain of events in his meticulously-researched and wide-ranging book, War of Shadows: Codebreakers, Spies, and the Secret Struggle to Drive the Nazis from the Middle East, published by Public Affairs.

The cast of British, German, Italian, American, Egyptian, Palestinian and Jewish characters in it are staggering. They run the gamut from Claude Auchinleck, the commander of British forces in the Middle East, to Albert Kesserling, his German counterpart.

Also included are Alexander Kirk, the U.S. ambassador to Egypt; Miles Lampson, the British envoy in the Egyptian capital; Alan Turing and Marian Rejewski, British and Polish codebreakers; Mustafa Nahas, the prime minister of Egypt, and Rodolofo Graziani, an Italian general whose army invaded Egypt.

Gorenberg’s narrative starts in the summer of 1942 as the victorious Afrika Korps was poised to attack El Alamein. Defended by Britain’s Eighth Army, it was commanded by General Bernard Montgomery.

With fear setting in that the Germans might conquer Egypt, the British embassy in Cairo began burning top-secret documents. Lampson, in the meantime, reported that Egyptian Jews were in panic mode over the nightmarish prospect that German soldiers might soon be marching through the city.

The British were in awe of Rommel. “We have a very daring and skillful opponent,” Prime Minister Winston Churchill said. German propagandists hammered home the point by glorifying Rommel as the symbol of the blitzkrieg and the epitome of Aryan manhood.

Expecting a German breakthrough, the U.S. ambassador predicted that Rommel would first strike Cairo rather than Alexandria. Moshe Shertok, a senior Jewish Agency official, feared an impending German invasion of Palestine, “It’s possible there will be atrocities here,” he said.

Sensing that danger loomed, the British built anti-tank fortifications on Mount Carmel in Haifa. Under the direction of a British general, the Palmah, a new Jewish fighting force, assembled a special unit to destroy roads and railway lines and ambush German troops in case the Wehrmacht entered Palestine.

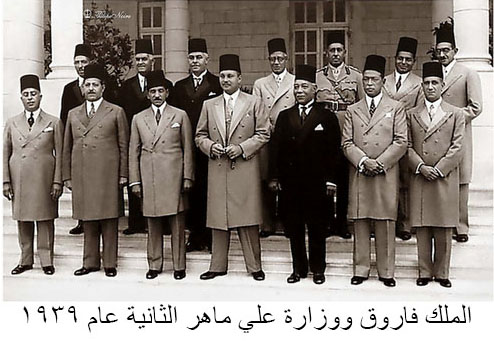

In Cairo, British diplomats wondered whether Egypt could be a reliable ally in the struggle against Germany and Italy. “There is already a genuine background of popular discomfort and resentment” that could make Egyptians receptive to Axis propaganda, Lampson warned. One such Egyptian, Anwar Sadat, was a signals officer in an artillery brigade. He would become president in 1970 after the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Britain believed that King Farouk was creating an “increasingly anti-British atmosphere” in the country, and that the chief of staff of the Egyptian army, Aziz el-Masry, was playing a similar role.

Given these suspicions, Britain was prepared to use force to ensure that Egypt remained in the Allied camp. Britain had no compunctions about throwing its weight around in the region. In August 1941, two months after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Britain and its new ally, the Soviet Union, invaded neutral Iran to secure Iranian oil fields, curtail German influence in the country, ensure the safety of Allied supply lines to Moscow, and preempt a possible move by Germany through Iran toward the Baku oil fields.

Unlike in Egypt, the British harbored no fear that the Jewish community in Palestine would turn pro-German. Although Jewish leaders opposed Britain’s policy in Palestine, particularly its White Paper on Palestine’s future, they urged young men to enlist in the British army. As David Ben-Gurion, a leading Jewish politician, said in 1939, “We must assist the British in the war as if there were no White Paper and we must resist the White Paper as if there were no war.”

The Palestinian leadership conveyed a diametrically different message. One of its leading figures, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, met with Adolf Hitler in 1941 to solicit his support for the independence of Palestine, Syria and Iraq. Hitler told him that Germany was against a Jewish national home in Palestine, and that once the Wehrmacht pushed through the Caucasus mountains into the Middle East, Germany’s objective would then be “solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere under the protection of British power.”

Hitler meant what he said. An army officer named Hans-Joachim Weise was instructed to create a mobile killing squad, an Einsatzgruppen, that would be attached to Rommel’s Afrika Korps. This task was subsequently assigned to Walther Rauff, whose order was to murder the Jews of Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq.

In Iraq, in April 1941, four pro-German Iraqi colonels staged a coup that temporarily restored the premiership of Rashid Ali al-Gailani. Shortly afterwards, Iraqi troops surrounded a British air base west of Baghdad and threatened to shoot down any plane that took off. The British proceeded to oust Gailani, who fled to Germany by way of Turkey. Blaming Iraqi Jews for his fall, his enraged supporters launched a pogrom in Baghdad in June of that fateful year.

The Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, vented his rage against Libyan Jews. In 1942, he issued a decree calling for their expulsion to Giado, a concentration camp southeast of Tripoli. The 700 or so Jews sent there endured harsh conditions.

With the war in North Africa still favoring Germany, Hitler assured Mussolini that Rommel’s conquest of Egypt was imminent. Hitler held Rommel in high regard, promoting him to field marshal after the Afrika Korps captured the strategic Libyan town of Tobruk. Rommel himself thought that victory was on the horizon. “There’ll be a few more battles to fight before we reach our goal,” he wrote his wife.

German and Italian field commanders were so confident that the British would be defeated that the Afrika Korps’ chief medical officer told his subordinates that they needed to take precautions against smallpox and to prevent soldiers from drinking unboiled water and buying ice cream from street vendors in Cairo.

In the meantime, British cryptographers had broken Germany’s military code and knew exactly what was going on behind its lines. Rommel needed reinforcements and was short of trucks, fuel and ammunition.

As a result of logistical problems, Rommel’s campaign to capture El Alamein stalled. “With the failure of this offensive, our last chance of gaining the Suez Canal has gone,” he wrote.

With Rommel’s retreat from Egypt, the danger of a German invasion of Palestine vanished. In short order, the United States and Britain launched Operation Torch in Morocco and Algeria. In response, 70,000 German and Italian troops marched into Tunisia, which would be the last Axis foothold in Africa.

Tunisian Jews were rounded up and dispatched to labor camps. Hefty fines were imposed on the Jewish community. Several Jewish leaders were deported to Nazi extermination camps in Europe.

The Axis occupation of Tunisia was of short duration. “Africa was liberated,” writes Gorenberg.