Of all the books I’ve read about the ongoing civil war in Syria, Syrian Requiem: The Civil War And Its Aftermath is the best of the lot. Written by the Israeli scholars Itamar Rabinovich and Carmit Valensi and published by Princeton University Press, it is concise yet comprehensive, scholarly yet accessible.

The authors are distinguished scholars.

Rabinovich, the president emeritus of Tel Aviv University, has churned out books and monographs about the Arab world and was Israel’s chief negotiator at peace talks with Syria in the early 1990s. He was also the Israeli ambassador to the United States.

Valensi is the director of the Syria research program at the Institute for National Security Studies in Israel.

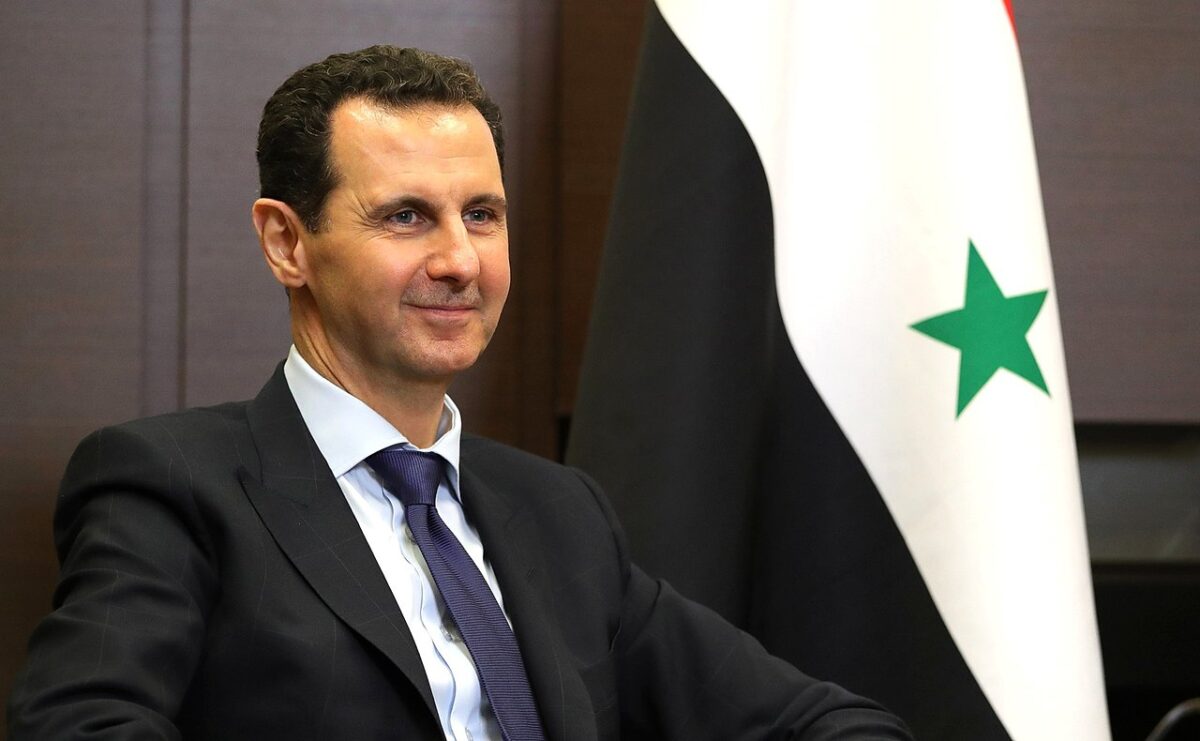

As they argue in the preface, Syria as it existed prior to this cataclysmic upheaval is “unlikely to be restored any time soon.” The regime of President Bashar al-Assad has practically defeated its adversaries and now controls about 60 percent of Syria’s land mass. But his sway over large parts of it is limited, and many Syrian Sunni Muslims, comprising the majority of the population, do not and will not accept his legitimacy.

Twelve million Syrians are internally displaced and six million, including the bulk of Syria’s Christian community, have fled and are unlikely to return.

Assad’s chief allies, Russia and Iran, intend to deepen and expand their influence in Syria, where about 450,000 soldiers and civilians have been killed in a decade of internecine warfare. Two of Syria’s immediate neighbors, Turkey and Israel, have important interests in Syria and will pursue them come what may.

The authors examine the civil war against the backdrop of Syria’s history following its independence in 1946. Governed by a traditional Arab nationalist elite of mostly urban notables and landlords, Syria was torn by instability. Riven by internal divisions and conflicts and convulsed by successive military coup d’etats, Syria was a weak and fragile state.

While 60 percent of its citizens were Sunnis, 10 percent were Alawis, 10 percent were Arab Christians, 10 percent were Kurds, and the rest were Druze, Ismailis and Christian Armenians. Syrian Jews were gradually driven out after the birth of Israel in 1948.

In the spirit of pan-Arab nationalism, Syria and Egypt amalgamated in 1958 to form the United Arab Republic, which broke apart in 1961. Two years later, a group of army officers identified with the Ba’ath Party staged a coup. The Ba’ath has been in power ever since, though it has undergone several transformations. Offering a secular version of Arab nationalism, combined with a social democratic ideology, the Ba’ath appealed to minority communities and younger men critical of the ruling elite and seeking change.

The Alawis, traditionally a downtrodden community manipulated by colonial France and exploited by Sunnis and tribal chiefs, formed a disproportionate percentage of the Ba’ath’s membership and were overrepresented in the new regime in terms of the senior positions they held in the government and the armed forces.

Two generals, Hafez al-Assad and Salah Jadid, jockeyed for dominance. Assad, the commander of the air force and the minister of defence, prevailed in a coup in 1970. He proceeded to transform Syria into a stable autocracy.

Assad’s regime was built around his family and his Alawi clan, but he was clever enough to place Sunnis in key positions and to ensure that the Sunni bourgeoisie in major cities enjoyed prosperity. As a result, some Sunnis had a vital stake in the regime’s durability and survival.

Political opposition was not tolerated and Syria under Assad was little more than a dictatorship. When open rebellion loomed, Assad was merciless. In 1982, he crushed an Islamic fundamentalist uprising in Hama, killing more than 20,000 civilians and levelling a quarter of the city.

Assad maintained Syria’s alliance with the Soviet Union and established close ties with Iran after the 1979 Islamic revolution. In 1976, he sent his army into Lebanon, which was mired in a civil war. Assad’s move was tacitly endorsed by the United States and Israel.

Although Syria was staunchly anti-Israel and supported Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shi’a militia, Assad was something of a pragmatist. Insistent on reclaiming the Golan Heights from Israel, he entered into peace negotiations with several Israeli prime ministers from Yitzhak Rabin to Ehud Barak.

Assad died in 2000 and was succeeded by one of his sons, Bashar, who had been training as an ophthalmologist in London. Initially, he seemed like a breath of fresh air. He pardoned political prisoners, granted political parties the right to publish newspapers, and tolerated discussion forums. Within a year, he showed his true colors and squelched dissent. As Rabinovich and Valensi observe, he regarded Syria as a family business. “He was less a forward-looking liberal modernizer than a quintessential product of the system he inherited,” they write.

Nonetheless, Assad had to contend with internal dissension. It was spearheaded by the Sunni vice-president, Abd al-Halim Khaddam, the former defence minister, Mustafa Tlas, and a bevy of activists who called for “peaceful, gradual” reform.

According to the International Crisis Group, Syria was in dire need of an overhaul. In a 2004 study, the ICG noted that Syria’s economy “is plagued by corruption, ageing state industries, a volatile and under-preforming agricultural sector, rapidly depleting oil resources, an anachronistic educational system, capital flight and a lack of foreign investment.” Cognizant of the regime’s resistance to real reform, the ICG said that “the elites … are wary of change and are attached to a formula that so far has served them well.”

The U.S. embassy in Damascus, in a cable in 2006, reported that Syria “continues to be dominated by a ‘corrupt class’ who use their personal ties to … the Assad family and the security services to gain monopolistic control over most sectors of the economy while enriching themselves and the regime beneficiaries.”

The government’s decision to drastically reduce subsidies, along with a corresponding increase in inflation, contributed to a sharp drop in the standard of living of most Syrians. A drought in eastern Syria between 2008 and 2011 forced tens of thousands of farmers to migrate to the cities and live in miserable shanty towns.

“The explosive potential of these developments was magnified by a trend that the regime either failed to notice or greatly underestimated: the proliferation of radical Islamic currents,” the authors say.

Assad’s liberalization and privatization of the economy added to Syria’s ills. He created a new economic elite beholden to him and his family, and while it grew richer and engaged in ostentatious consumption, the lower middle class and the working class suffered, buffeted by dramatic declines in salaries and income and the reduction of subsidies on food and oil.

As Arab Spring revolutions tore through Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, Syria seemed to be an island of calm. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal in January 2011, Assad insisted that Syria was immune to revolutionary turmoil.

These were famous last words.

The first anti-regime protests took place in March 2011 in Dara — a city near the Jordanian border — and then spread to Latakia and Deir ez-Zor. The two largest cities, Damascus and Aleppo, remained quiet, at least for a while. Christians and Druzes played a minor role in these protests, preferring Alawi predominance to the prospect of an Islamist Syria.

The regime’s response was two-fold. It cracked down hard with arrests, torture and murder. And it unveiled a series of limited reforms and symbolic concessions. “Such measures proved to be futile and, in fact, exacerbated the public’s frustration,” the authors point out.

In a turning point, Assad ordered the army to quell the demonstrations. Tanks and artillery, as well as fighter jets and helicopters, were used against unarmed civilians. Eventually, Assad deployed chemical weapons. Justifying his cruel and unusual methods, Assad claimed he was facing a foreign conspiracy rather than a genuine grassroots revolt.

Rabinovich and Valensi believe Assad provided his supporters with “single-minded, cool-headed and ruthless leadership.” To Assad, brutal suppression guarantees survival and compromise is a slippery slope to be avoided. This philosophy has been his guiding rationale for the massive use of force against his enemies.

The uprising morphed into a full-fledged civil war between July and December 2011. During this pivotal period, the Free Syrian Army was the main military arm of the rebels, radical Islamic militias joined the fighting, and several high-ranking government leaders, including the minister of defence, were killed.

Both sides played the sectarian card. The regime consolidated support from both the Alawi community and non-Sunni groups. The opposition relied on Sunnis.

As the civil war unfolded, Russia, China, Iran and Hezbollah provided military aid and political support. The United States, its European allies, Turkey and most Arab states denounced the regime.

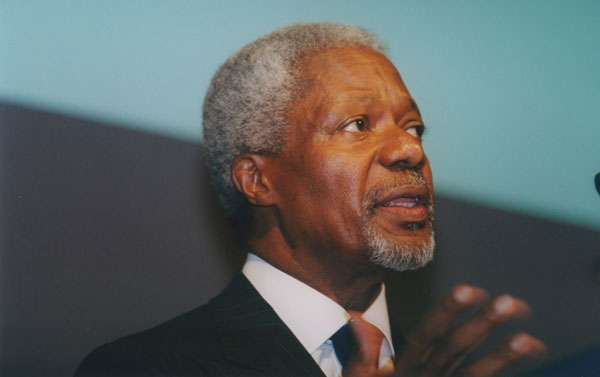

The former secretary general of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, was appointed as a mediator, but he resigned. He was replaced by a succession of new mediators who achieved nothing of substance. In the absence of a settlement, civilian casualties rose and more Syrians fled into adjacent countries, creating a humanitarian crisis.

The authors are critical of U.S. President Barack Obama. He warned Assad he would face consequences if he crossed a “red line” by using chemical weapons against civilians. When Assad called his bluff in 2013, Obama scrambled to reach an agreement with Russia to dismantle Syria’s arsenal of chemical weapons. “Obama’s decision to avoid military action despite the crossing of his red line had a devastating effect on the Syrian opposition,” write Rabinovich and Valensi.

This episode paved the way for Russia’s military intervention in 2015 in partnership with Iran. Moscow was influenced by three considerations. Assad’s regime had to be saved from collapse. Thousands of Muslim jihadis from the Caucasus and Central Asia had joined Islamist militias opposed to Assad, and they had to be eliminated. Russia sought to resurrect its greatness by restoring its clout in the Middle East.

With the regime losing territory by the day, Russian President Vladimir Putin sent fighter jets and air defence batteries to the Khmeimim air base and dispatched officers and technical experts to be integrated into the Syrian army. “Once Russia joined the fray, its air force made a catastrophic difference with massive, and often indiscriminate, bombing,” they say.

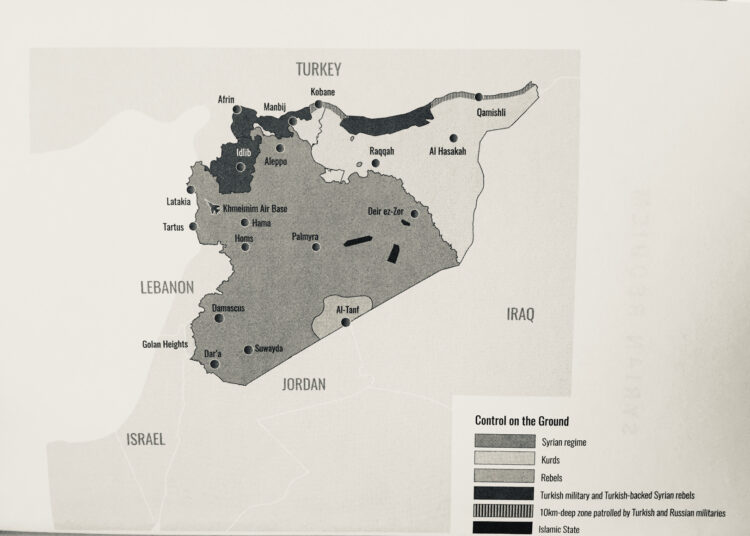

By 2018, Assad had recaptured some lost land. Today, Idlib province remains the rebels’ last stronghold.

U.S. policy under Donald Trump’s administration, they note, was characterized by “fluctuations and lack of order.” Trump announced the withdrawal of 2,000 U.S. troops from eastern and northeastern Syria, only to scale back his directive. Trump, however, gave Israel carte blanche to degrade Iran’s military infrastructure in Syria.

The United States’ most effective ally in Syria, the Kurds, remained neutral in the early phase of the civil war. The People’s Protection Units, the military wing of the Democratic Union Party — the Syrian branch of a Kurdish party in Turkey — would control a sizeable segment of northern Syria near the Turkish border. Kurdish fighters, backed by U.S. air power, battled the Islamic State, which emerged in Iraq during the American occupation and expanded into Syria.

Three regional powers — Iran, Israel and Turkey — have played major roles throughout the civil war.

Iran’s policy went through different stages, evolving from straightforward support of a valued ally to a quest to further its hegemonic ambitions in the region. Iran’s alliance with Syria was based on shared interests: common enmity to the United States and Israel, Syria’s willingness to provide Iran with access to its Shi’a constituency in Lebanon, and Tehran’s willingness to offer Syria’s minority Alawi rulers Islamic legitimacy.

After 2015, Iran abandoned its policy of indirect military intervention in Syria and sent elements of the Iranian army and the Quds Force to assist the Syrians. From Iran’s perspective, Syria was its most important Arab ally and a crucial link to its most successful foreign policy investment — Lebanon and Hezbollah.

Around 2017, Iran expanded the scope of its presence in Syria. Tehran recruited Shi’a militias from the Muslim world to fight alongside the Syrians. In addition, Iran built missile bases and factories for the production of precision-guided missiles in Syria. Iran also started to construct a land bridge to transport military supplies from Iraq to the Mediterranean Sea.

Iran’s overarching strategy was to entrench itself militarily in Syria so as to create a new front against Israel on the Syrian side of the Golan. “The motivation of undertaking such a massive investment — and the risks it entailed — was driven at its core by a deep, powerful antagonism toward Israel and Zionism,” Rabinovich and Valensi contend.

Israel’s policy toward Syria shifted as circumstances changed. During its earliest phase, Israel tried to keep aloof from the conflict. The Israeli government, however, offered medical care and food to mainstream Syrian rebels and civilians near its border. Israel retaliated when its territory was struck by errant Syrian shells. Israel interdicted the flow of sophisticated Iranian weapons to Hezbollah en route from Syria to Lebanon.

Fearing that Iran and Hezbollah were trying to establish a terrorist base in the Syrian Golan, Israel began cooperating with local militias in Syria. Subsequently, the Israeli Air Force carried out hundreds of raids against Iranian sites in Syria and bombed Syrian anti-aircraft batteries when necessary.

Russia’s bold intervention threatened Israel’s freedom of action in the skies of Syria and Lebanon and raised concerns about the possibility of an Israeli clash with Russian aircraft. These considerations led Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to reach an understanding with Putin regarding the disposition of Israeli and Russian forces in Syria.

“Although it was Iran’s ally and partner in Syria, Russia was also committed to maintaining a good working relationship with Israel, and possibly limiting Iran’s influence in Syria,” Rabinovich and Valensi say.

Following an incident in 2018 during which a Russian reconnaissance plane was accidentally shot down by Syrian missile batteries, Russia imposed limits on Israeli air raids. This interregnum lasted for only a few months. To this day, Israel continues to attack Iranian targets in Syria without Russian interference.

Before the civil war, Turkey enjoyed cordial relations with Syria. With the eruption of the uprising, Turkey tried to persuade Assad to offer genuine concessions to his critics. Assad paid no heed to these suggestions, prompting his former Turkish friend and mentor, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, to call for his resignation and to compare him to Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

With the passage of time, Turkey morphed into an enemy, providing the Syrian rebels with arms and a direct land corridor into Syria. Turkey became a gateway for jihadists heading to the battlefields of Syria. Islamic State fighters received medical treatment in Turkish hospitals and businessmen in Turkey bought oil from Islamic State.

More concerned by the buildup of Kurdish forces south of its border with Syria than with Islamic State territorial gains, the Turkish army launched a series of raids into Syria and occupied territory there. Tensions with Russia temporarily skyrocketed when the Turkish Air Force downed a Russian jet.

In Rabinovich’s and Valensi’s view, the outcome of the civil war was essentially settled in December 2016 when the Syrians, in a combined assault with Russia and Iran, recaptured Aleppo. “The conflict has been waning ever since,” they add.

Idlib, though, is still in the hands of rebels. The Kurds occupy swaths of northern and southeastern Syria. Turkey has established an enclave in Syria along its southern frontier.

The Islamic State’s caliphate in Iraq and Syria has been eradicated, but it conducts guerrilla attacks in eastern Syria and is likely to exploit Sunni resentment of Alawi control and Shi’a influence to challenge the regime. Another challenge facing Assad are Russia’s and Iran’s “enhanced ambitions” in Syria.

The five million Syrian refugees in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon pose a major obstacle to reconstruction and economic recovery, they write.

And Assad still believes that significant reform is not necessary to establish legitimacy and stability.

The survival of his regime is due to several factors. He has displayed resilience and ruthlessness. The opposition is weak and divided and does not offer Syrians a credible alternative. Sunnis and Christians fear a jihadi takeover of Syria and thus prefer Assad, the devil they know. Russia and Iran have been unwavering in their support. The United States has been very reluctant to be sucked into the civil war.

In closing, Rabinovich and Valensi express gloom over Syria’s future.

“The road to full normalization for the Syrian state seems insurmountable, considering the daunting list of obstacles (it) faces. These include the continuing refusal of significant parts of Syrian society to accept (Assad) as a legitimate ruler, the challenge of overcoming the trauma of the disastrous civil war, the enormous difficulties to be faced in reconstruction, and the lingering issue of the refugees. The sharp divisions that tore Syrian society apart on the eve of the civil war have only been exacerbated, and Assad is not … a healer.”

Syrians will have to wait a lot longer to see the light at the end of a very long tunnel.