Once bitten, twice shy.

Mahmoud Abbas, the 85-year-old president of the Palestinian Authority and the leader of the mainstream Fatah party, was taking no chances. On April 29, he postponed the Palestinian parliamentary election, which was due to be held on May 22.

This came as no surprise to observers.

Abbas has been wary of elections since 2006, when his arch rival, Hamas, defeated Fatah, winning 74 of 132 seats in the Legislative Council.

A year later, Hamas seized full control of the Gaza Strip, triggering a brief civil war with Fatah and setting the stage for constant skirmishes as well as three border wars with Israel in 2008-2009, 2012 and 2014.

After the debacle of 2006, Abbas cancelled one election after another, fearing he might lose again.

As expected, Hamas — the still undisputed ruler of the Gaza Strip — blasted Abbas’s latest unilateral move. In a statement, Hamas said, “This represents a coup against the path of partnership and national consensus. Our popular and national consensus cannot be pawned as collateral for the agenda of a faction.”

Abbas, who called the election in January, blamed Israel for his unpopular decision, citing Israel’s refusal to confirm its stamp of approval of voting in East Jerusalem. As reports suggest, the Israeli government neither blocked nor approved of the election, leaving the situation murky.

Under the 1993 Oslo agreement, Israel is obliged to allow Palestinian elections in eastern Jerusalem, which was annexed by Israel in 1967 and which is claimed by the Palestinian Authority as the future capital of an independent Palestinian state.

In the run up to the election, the Israeli police detained a number of Palestinian politicians in East Jerusalem campaigning for office, thereby discouraging Palestinian voters, technically residents of Israel, from exercising their democratic right to vote.

Israel’s position is hardly a mystery.

Israel has done everything possible to disabuse the Palestinians of the notion that they may acquire sovereignty in East Jerusalem one day. To Israel, the worst case scenario would be a victory for Hamas, which has turned Gaza into an impoverished armed camp.

Conversely, the Palestinian Authority regards East Jerusalem as its sovereign territory and Hamas as a dangerous foe which must be contained.

In an important sense, then, the idea of a Palestinian election in East Jerusalem was part of a bigger struggle pitting Israel against the Palestinian national movement.

On a micro level, the postponement of the election was about the bitter political rivalries within the fractured Palestinian community.

Abbas hoped that it would confer greater legitimacy on his leadership, but after rivals in the Fatah movement declared their candidacies in March, he began to have second thoughts.

His most serious challengers were from three Fatah veterans.

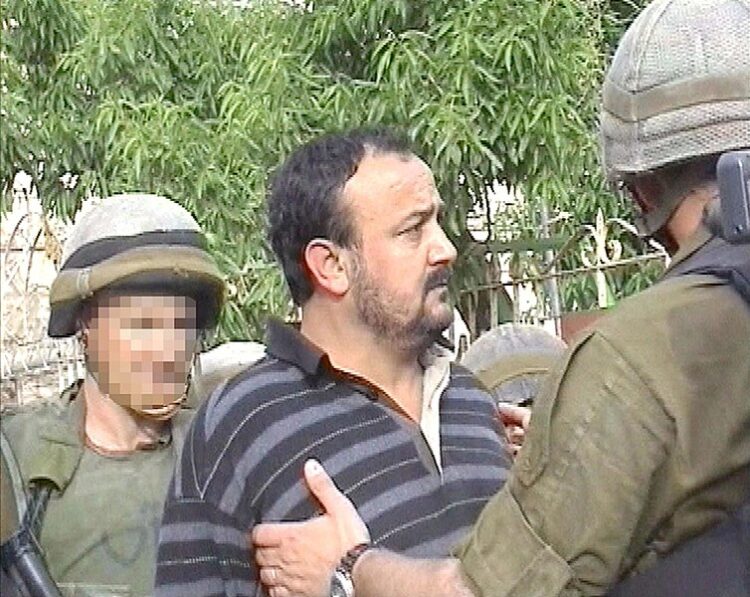

The contender with the greatest appeal, Marwan Barghouti, has been locked up in prison for nearly two decades. A charismatic activist who commands the loyalty of many Palestinians, he was sentenced to five consecutive life terms for his role in the murder of five Israelis during the second Palestinian uprising, which erupted in September 2000. In 2004, he challenged Abbas for the presidency, but withdrew and threw his support behind Abbas, who succeeded Yasser Arafat as president following his death in 2004.

The two other challengers were Nasser Kidwa, Arafat’s nephew and the former Palestinian representative at the United Nations, and Mohammed Dahlan, Fatah’s former head of security in the Gaza Strip and today a resident of the United Arab Emirates.

Given Israel’s unyielding policy of keeping all of Jerusalem under its sovereignty and the Palestinians’ stance that Arab residents of East Jerusalem have a right to vote, it is extremely unlikely that the Palestinian Authority will call new parliamentary election any time soon.

As for Palestinian presidential elections, they have not taken place since 2005, when Abbas won a four year term. In the intervening years, he declined to call fresh elections, prompting wags to quip that he had implicitly declared himself president-for-life, like Vladimir Putin of Russia.

A new presidential election is scheduled for July 31, but whether it goes ahead is debatable.

Since the formation of the Palestinian Authority in 1993, Palestinians have had very few opportunities to vote in elections, compared to the dizzying array of elections in which Israelis have voted during the same period.

While Israelis suffer from a surfeit of elections, a record four in the last two years, Palestinians dream of voting in even one election, which has been postponed yet again.