Prodigious and prolific, Irving Layton was one of Canada’s most accomplished poets when Donald Winkler of the National Film Board of Canada was assigned to direct a documentary about him. Fifty two minutes in length and released in 1986, Poet: Irving Layton Observed will be streamed online by the NFB in May during Canadian Jewish Heritage Month.

This is not a straightforward biopic, but a cinematic rumination in praise of a stellar literary figure who modestly describes himself as a “shy and decent fellow.”

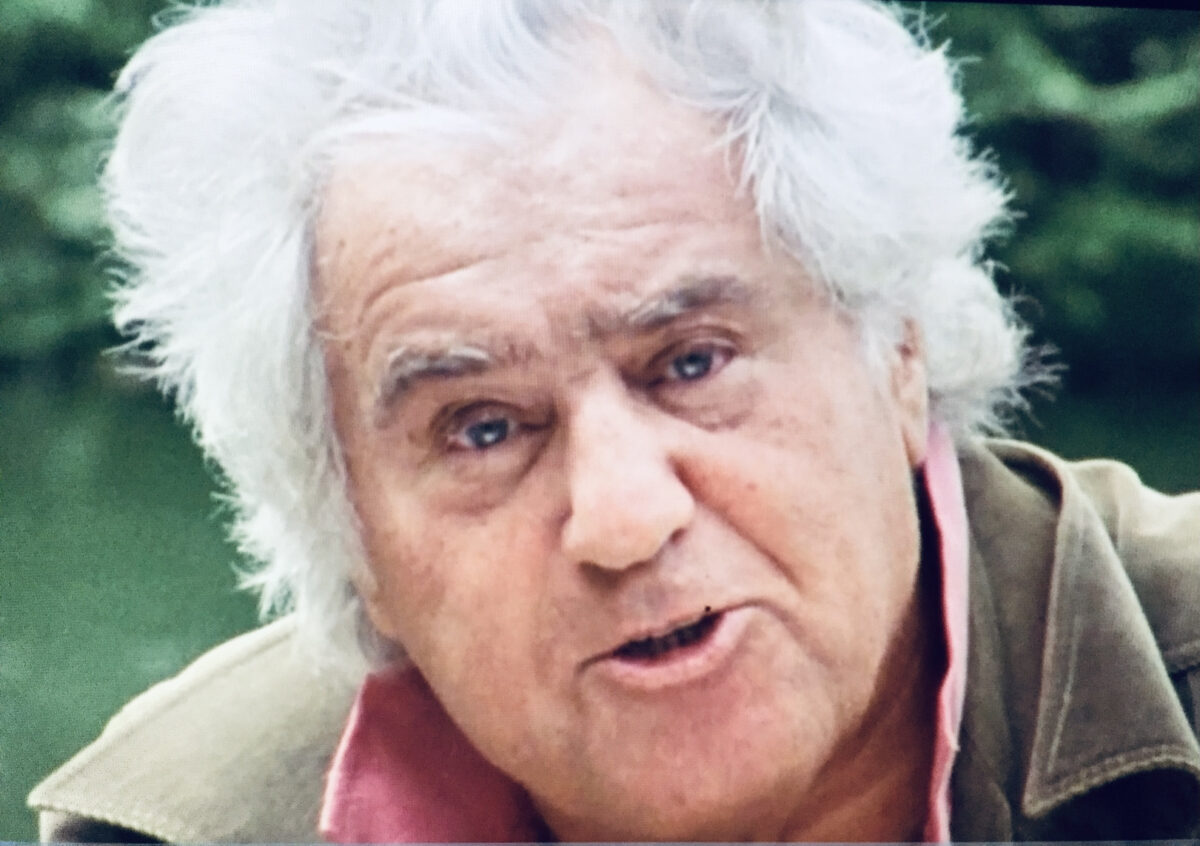

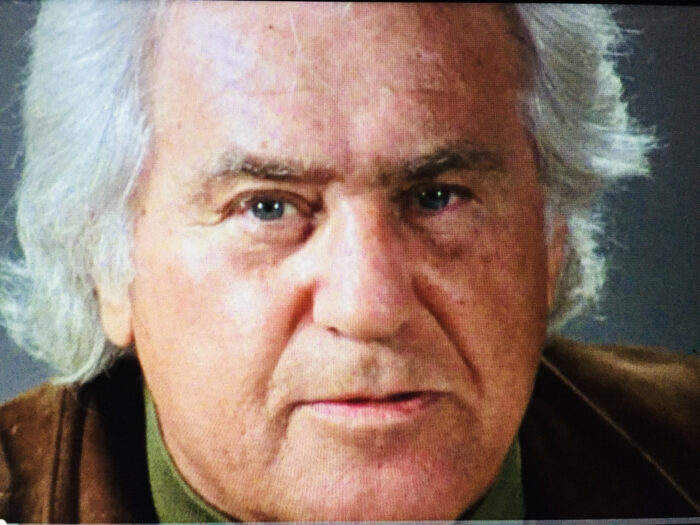

Sporting a mane of white hair, the loquacious Layton waxes eloquently as he discusses the dynamics of poetry and, to a much lesser extent, himself.

“I want to make this clear,” he says in the opening frame. “The poet is a different kind of animal. He has bacon and eggs in the morning, like everyone else, and he will even brush his teeth, I’m quite sure, and polish his shoes.”

“But there is something about him that is not ordinary,” he adds. “A poet is an abnormal rather than extraordinary … So let’s agree. There’s something abnormal about the poet.”

Layton, whose books of poetry ranged from A Red Carpet for the Sun to Dance With Desire, was certainly unconventional, but he was not abnormal.

Israel Pincu Lazarovitch was born in a small town in Romania. He and his family immigrated to Canada when he was an infant. He grew up in Montreal, whose qualities he savors. “To me, Montreal will always be the city of churches, brothels and writers,” he says. “For me, Montreal is like Paris must have been to writers of the 1920s.”

Layton graduated from a local college and taught at a Jewish parochial school in Montreal before landing a teaching gig at York University in Toronto. Somewhere along the line, in keeping with the temper of the times, he anglicized his name.

He was married five times. His last wife, Anna Pottier, was 48 years younger and originally his housekeeper.

In his estimation, the function of a poet is to warn readers of the “dangerous pollutants” and “demons” in the human soul and in society at large. He mentions antisemitism, racism, injustice and social and economic inequalities.

He regrets that poets have not been able to provide “enlightenment” on the Holocaust, “the most terrible event in human history.”

Calling himself a “visual poet” who’s drawn to strong and striking images, Layton says he rejoices in the power of poetry because it keeps him fully alive and removes chaos from his life. Claiming he translated his father’s piety into poetry, he says, “I’m my father’s child.”

The locale of the film shifts from Toronto to Athens as he travels to Greece to deliver a round of lectures on Canadian poetry. Layton contends that “extremely sophisticated” poetry has been produced in Canada and that it is distinctly Canadian. Is he referring to himself? To his prodigy, Leonard Cohen? Or to someone else out there? We will never know because he mentions no names.

As he sits amid the ruins of a Greek temple, he composes a poem. “Very good, very good,” he muses. “Believe it or not, we have something.”

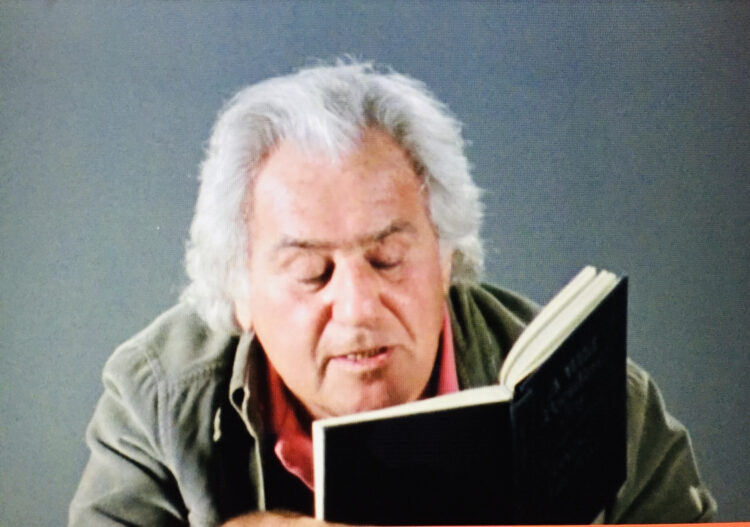

A poem brings satisfaction to Layton when its words are like music, when it dances off the page and when it delights and startles a reader. Yet a good poem doesn’t “gush out” of his pen effortlessly. It needs to be rewritten until it is just right.

During the course of his visit, he spends some of his time with a woman who will translate one of his books into Greek. At a taverna, he and his wife take to the floor to dance to the beat of Greek music.

As he readily admits, his three most favorite activities are writing, making love and teaching.

Toward the close of the film, he discloses he is writing his memoirs. It will be published under the title of Waiting for the Messiah. Layton is a busy man, but time is running out on him.