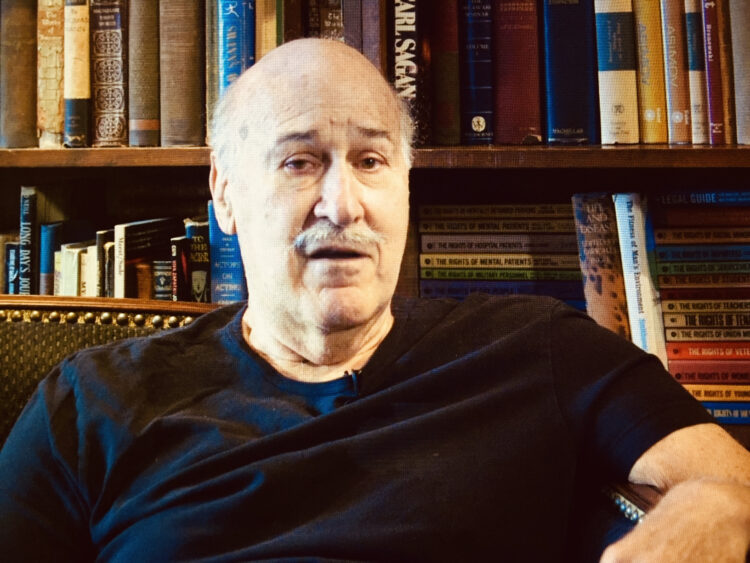

Ira Glasser led the American Civil Liberties Union from 1978 until 2001, transforming what had been a fairly obscure and somnolent group into a high-profile national organization. Mighty Ira, a documentary directed by Nico Perrino, Chris Maltby and Aaron Reese, sheds light on the dedicated and principled man who directed this process.Their engaging movie will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 3-13.

Glasser grew up in Flatbush, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. He was nine years old when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team in 1947 and became the first African American to break the color barrier in major leagues sports. It was a seminal moment, not only for race relations, but for Glasser, a fanatical Dodgers fan.

Having been raised in an entirely white and Jewish urban milieu, Glasser had been totally unaware of the Jim Crow racial injustices that plagued the United States. Indeed, he did not realize that polyglot New York City, a supposed melting pot, was really “a collection of insular segregated tribes.”

Glasser’s hatred of racism moulded him, as did the stifling atmosphere of “political acquiescence and intimidation” that prevailed during the McCarthyist era of the early 1950s.

With the onset of the 1960s, America began to change for the better, and Glasser developed a strong desire to be involved in progressive political activities. He wrote a letter to Senator Robert Kennedy (New York), urging him to run in the next U.S. presidential election. Much to Glasser’s surprise, Kennedy invited him to his office for a chat.

A month later, Glasser was named the associate director of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Glasser regarded the job as a stopgap. “I had no idea it would lead to a lifetime career and the career of my dreams,” he says.

Shortly afterwards, Kennedy announced his bid for the presidency, which was abruptly cut short with his assassination in 1968, the year the African American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered by a white supremacist.

As Glasser settled into his position, he prioritized his top two objectives — racial justice and organizational survival.

He got his chance to make a difference in 1978 when the leader of the American Nazi Party, Frank Collin, made a sensational announcement. He and his followers would stage a march through Skokie, Illinois — a suburb of Chicago where 7,000 Holocaust survivors lived — on the July 4th national holiday.

Collin explained that his stunt was intended to test the limits of free speech under the First Amendment. At Collin’s request, the American Civil Liberties Union accepted his case, much to the consternation of many Skokie residents

Glasser says he was defending the concept of free speech rather than protecting Collin and his ragtag bunch of Nazis. If the American Civil Liberties Union had passed on the case, he adds, the federal government would have been emboldened to restrict free speech across the board, and First Amendment petitions in support of social justice causes would have fallen by the wayside.

With the U.S. Supreme Court having upheld the Nazis’ right to march in Skokie, Collin cancelled the much anticipated event and rescheduled it in a southern Chicago park near his home turf. Collin and his ruffians were met by a hostile crowd, and their moment in the sun was drowned out by the protesters.

To Glasser, Skokie was a “defining chapter” in the annals of the American Civil Liberties Union. Although its purist position upset some Jewish supporters, Skokie solidified the cause of free speech and thrust his organization into the limelight.

Once the dust had settled, two embarrassing revelations forced Collin out of the American Nazi Party. News emerged that he was the half-Jewish son of a Holocaust survivor who had been imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp, and that he had sexually molested boys.

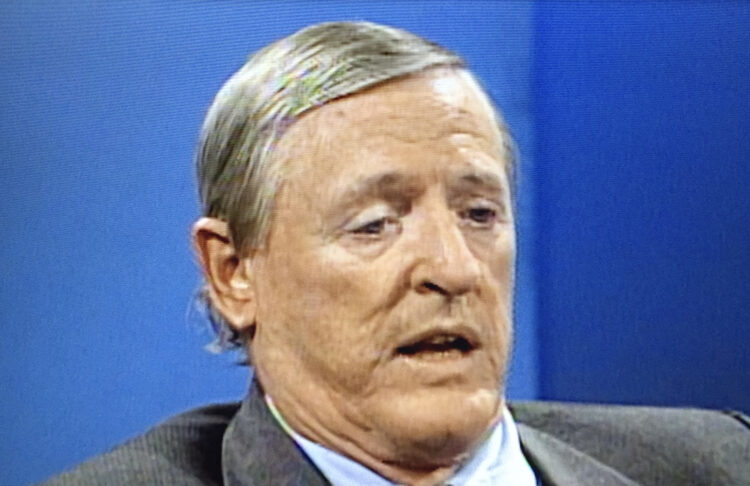

As these events unfolded, Glasser, a liberal, established friendly relationships with the conservative editor of the National Review, William Buckley Jr., and with Ben Stern, a Holocaust survivor from Skokie who had stoutly opposed Glasser’s defence of the American Nazi Party.

Not surprisingly, Glasser supported the right of white supremacists and neo-Nazis to mount the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017.

In closing, the filmmakers praise Glasser as an activist who has worked mightily hard to protect American constitutional principles. “I certainly had my shot at it, and I was pleased to pass the baton on to others,” he says, summarizing his contribution to free speech in the United States.