Itamar Ben-Gvir is a disgrace to himself and Israel.

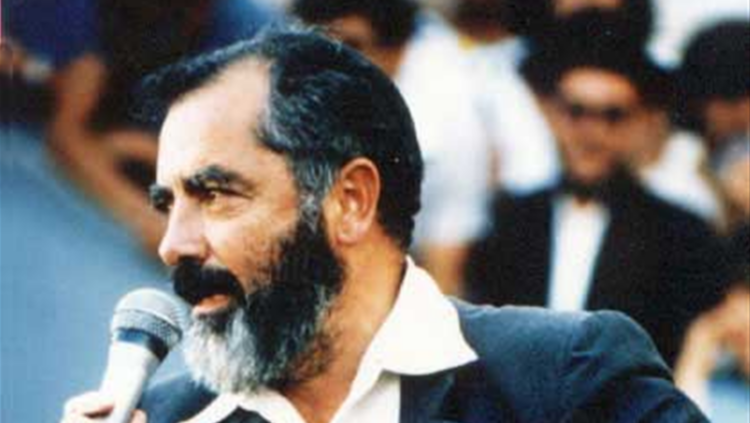

This extreme right-wing member of the Knesset is a malignant agitator who has been fanning the flames of the most serious outbreak of civil unrest in Israel since its establishment as an independent state.

As Jews and Arabs clash in inter-communal violence of the sort that convulsed Palestine during the British Mandate period, Ben-Gvir, an admirer of arch rabble-rouser Rabbi Meir Kahane, goes around the country stirring up passions.

In the days since the flareup of fighting between Israel and Hamas, the rioting has ebbed and flowed. Most recently, a theater in Acre, a symbol of Jewish-Arab coexistence, was burned by arsonists. And in Jaffa’s Ajami district, the home of an Arab family was firebombed, injuring two children. In Lod, which is under both a state of emergency and a curfew, police shot and wounded a person trying to throw a Molotov cocktail at a municipal building. In Ramle, two shops were torched.

Israel’s police commissioner, Kobi Shabtai, has reportedly told Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that Ben-Gvir is responsible for the riots. This is doubtless an exaggeration and an oversimplification, since the root causes of the violence are deep seated and complex and cannot be attributed to a single person.

But in Shabtai’s view, Ben-Gvir bears a great deal of responsibility for upending decades of coexistence between Jews and Arabs, who account for 20 percent of Israel’s population of nine million. On May 15, he admitted that the police were caught off guard by the violence. “There were a number of events we weren’t prepared to respond to simultaneously,” he said. “Today we are prepared with greater intensity, with a concentration of forces.”

According to Shabtai, Ben-Gvir and his unruly followers undermined police efforts to keep the rioting in check in cities such as Jerusalem, Lod and Ramle, where Arabs form a significant proportion of the population.

In particular, they acted provocatively at the Damascus Gate, which leads to Jerusalem’s Old City, and in Sheikh Jarrah, a neighborhood in eastern Jerusalem where Palestinian Arab families faced evictions from their homes, Shabtai says.

At these places, Ben-Gvir’s acolytes joined forces with a racist and reactionary outfit known as Lehava, which rails against Jewish-Arab mixed marriages, calls for the expulsion of Arabs from Israel and opposes gay and lesbian rights. To no one’s surprise, these hooligans shouted “Death to Arabs” as they staged their noisy marches in Jerusalem.

A lawyer who lives in a Jewish enclave in the West Bank town of Hebron, Ben-Gvir is a founder of the far-right Otzma Yehudit Party, or Jewish Power Party. Prior to Israel’s last general election, Netanyahu convinced him to merge his party with Bezalel Smotrich’s Religious Zionist Party, which won six parliamentary seats and catapulted Ben-Gvir into the Knesset.

Netanyahu calculated that the Religious Zionist Party, a vehement opponent of a two-state solution, could help him win a majority in parliament so that he could retain his position as prime minister, but Smotrich bitterly disappointed him.

He declined to join Netanyahu’s budding coalition because its survival would have been dependent on the support of an Arab politician, Mansour Abbas of the Islamist Ra’am Party, which picked up four seats.

Observers of Israel’s political scene were hardly surprised by this turn of events. Politicians like Smotrich and Ben-Gvir are not partial to cooperating with Arabs to achieve common goals. Indeed, they regard the Arab minority as a fifth column.

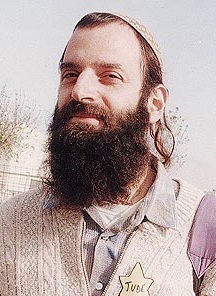

In this sense, their ideas are strikingly similar to that of Meir Kahane, the founder of the Jewish Defence League. A one-term member of the Knesset for the Kach Party in the mid-1980s, he was officially banned from running for office again in 1988. Two years later, he was assassinated in New York City by an American of Egyptian descent.

Yet his noxious ideas never died. One of his most ardent followers, Baruch Goldstein, an American-born physician who lived in a West Bank settlement, killed 29 Palestinians in a Hebron mosque in 1994. The ripple effects of this murderous rampage had a consequential impact. It provided Hamas with a pretext to launch an unprecedented campaign of suicide bombings throughout Israel, a tactic that Hamas would return to after the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000.

The Shin Bet, Israel’s internal intelligence agency, has described the unrest as “terror for all intents and purposes,” and sent agents to monitor the situation and arrest perpetrators. “We won’t allow violent rioters to impose terror on the streets of Israel, either by Arabs or Jews,” said its director, Nadav Argaman, on May 14.

Tellingly enough, Netanyahu has not publicly condemned Ben-Gvir, even though the police commissioner has already done so. One can only assume that his deafening silence is motivated by political expediency. Netanyahu may well need the backing of the Religious Zionist Party to survive politically.

In the meantime, Ben-Gvir seems free to pour oil on the fire.