Edward Ball’s great-great-grandfather, Polycarp Constant Lecorgne, was a racist who sought to restore white dominance in Louisiana during and after Reconstruction in the wake of the U.S. Civil War. A Creole from New Orleans whose ancestors hailed from Brittany in western France, Lecorgne was a “hero” of his times because he fought for “whiteness” in the service of the white supremacist cause.

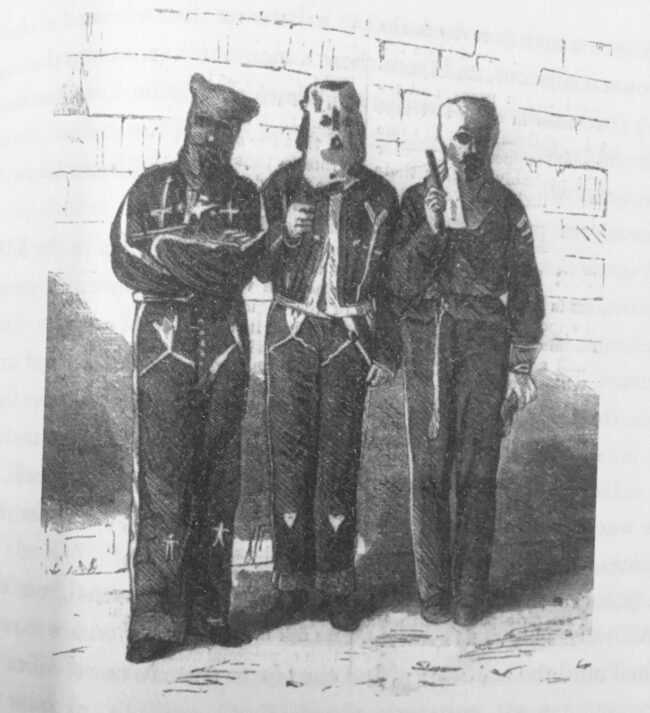

Lecorgne, a carpenter, was a foot soldier in the White League, a spinoff of the Ku Klux Klan. Its overriding objective was to roll back the achievements African Americans had attained during Reconstruction. During that historic interregnum, Northern troops occupied the defeated Southern states in the former Confederacy, and the U.S. Congress outlawed slavery, conferred citizenship on black slaves, and empowered them with the right to vote in local, state and national elections.

Calling themselves Redeemers, resentful white southerners like Lecorgne fought to end Reconstruction and place Louisiana — a former Spanish and French colony purchased by the United States in 1803 — back into white hands.

In his fascinating book, Life Of A Klansman: A Family History In White Supremacy (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Ball skillfully reconstructs these tumultuous events.

In his view, half of all American whites can claim a family link to the Ku Klux Klan, which was formed in Tennessee shortly after the Civil War. As he explains:

“In 1925, the Ku Klux Klan could claim five million members, white and Christian. It is likely that leaders in the movement exaggerated their numbers for publicity reasons. Let us assume that actual Klan membership stood at four million. Take four million Klansmen … and estimate the number of their descendants. Count forward one hundred years to their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. By a good formula in demography, the four million of 1925 have as their direct descendants in 2025 about one hundred thirty-seven million living white Americans. One hundred and thirty-seven million people comprise one-half of the white population of the United States.”

In other words, 50 percent of whites possess a family link to the Ku Klux Klan. “Perhaps the gentle reader of these words is one,” he writes. “If not, someone near you.”

Ball goes one step further by explaining the deeper meaning of his thesis. “White supremacy is not a marginal ideology,” he says. “It is the early build of the country. It is a foundation on which the social edifice rises, bedrock of institutions.”

As he points out in the first few pages of this volume, a work of reality based on court records and of imagination rooted in received knowledge, the tale he tells of Lecorgne transcends his family. “It is particular, but it carries with it a genealogy of race identity, of whiteness. It is a story of whiteness that is born into one life and grows, branching out into a tree that shelters others.”

Lecorgne and his wife, Gabrielle Duchemin, had six children. French was their mother tongue, which was spoken by white and black Creoles, the natives of Louisiana who comprised about 25 percent of New Orleans’ inhabitants prior to the Civil War. The language of commerce and politics was English, and its speakers were known as “les Americains.”

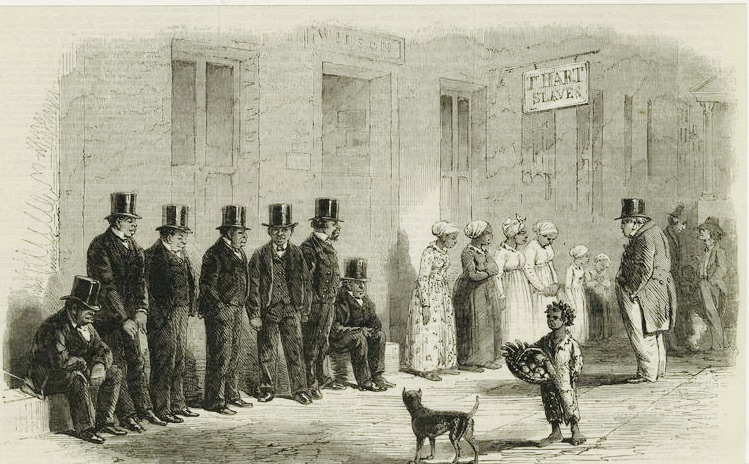

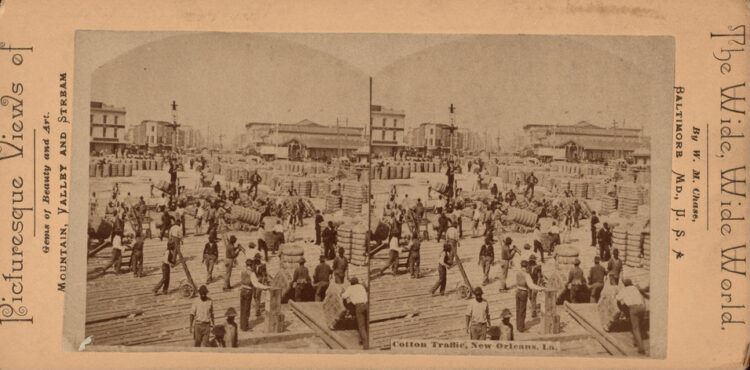

New Orleans was a racially mixed city, with its population more or less evenly divided between whites and blacks. In the decades leading to the Civil War, one-quarter of its whites were slaveholders and half of its black residents were enslaved. The rest, of mixed race descent, were free.

Louisiana seceded from the union shortly after South Carolina became the first southern state to join the Confederacy. One of its leading citizens, a Jewish lawyer and slaveholder named Judah Benjamin, would be the Confederacy’s secretary of state.

Like Lecorgne, Benjamin was a Democrat. The Democrats backed the status quo in the south, while the newly established Republicans, the party of Abraham Lincoln, regarded slavery as untenable. But as Ball notes, the majority of white Americans either supported slavery or were indifferent to it.

During the “war between the states,” as Southerners preferred to call the Civil War, Lecorgne was a junior infantry officer. At the end of that war, black politicians in Louisiana, aided and abetted by northern Republican reformers, amassed political power for the first time. Of 101 members of Louisiana’s legislature, 56 were Republicans, of whom nearly half were black.

In 1870, Mississippi sent Hiram Revels, a black cleric, to the U.S. Senate. At the end of that year, Joseph Rainey, a black barber from South Carolina who had been born into slavery, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Throughout the rest of the south, this pattern manifested itself.

The vast majority of white southerners, including Lecorgne, were appalled by these unprecedented developments. Charles Gayarre, a historian from Louisiana who witnessed the upheavals during Reconstruction, wrote, “We are completely under the rule of ignorant and filthy negroes scarcely superior to the orang-outing.”

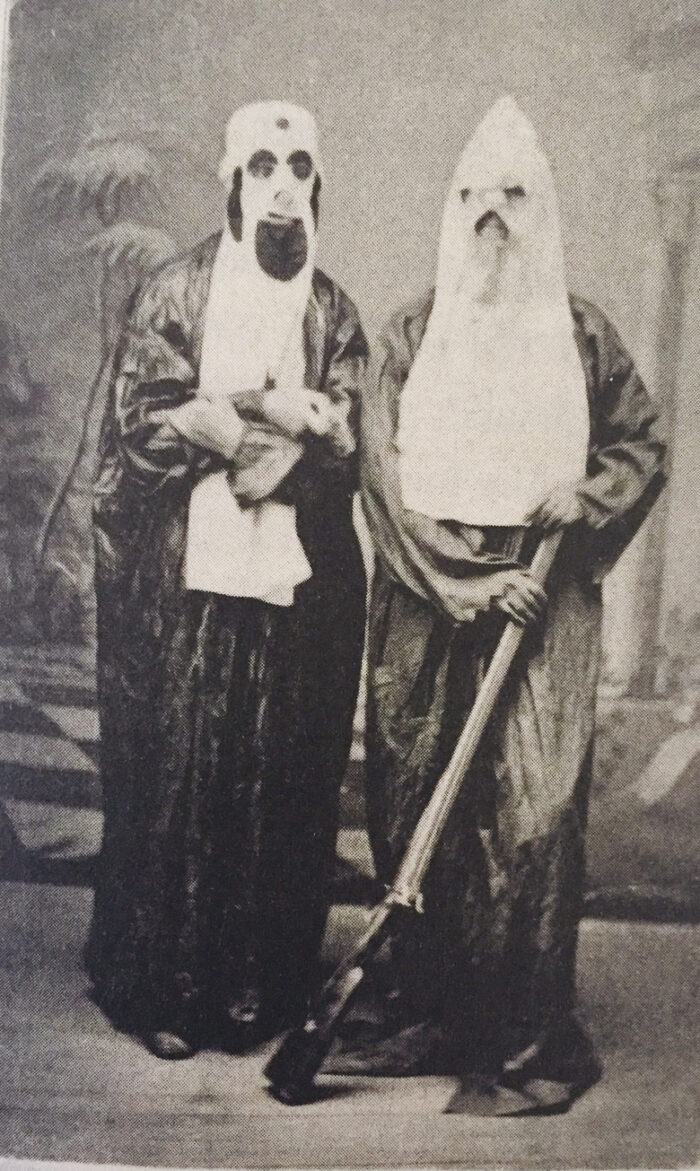

In this baneful spirit, Lecorgne was drawn to a convention of the Knights of the White Camellia in New Orleans. It issued a white supremacist manifesto that, Ball believes, was the first statement of its kind in the United States. Its leader, Alcibiade DeBlanc, said, “We know that the government of our republic was established by white men, for white men alone, and that it never was in the contemplation of its founders that it should fall into the hands of an inferior and degraded race.”

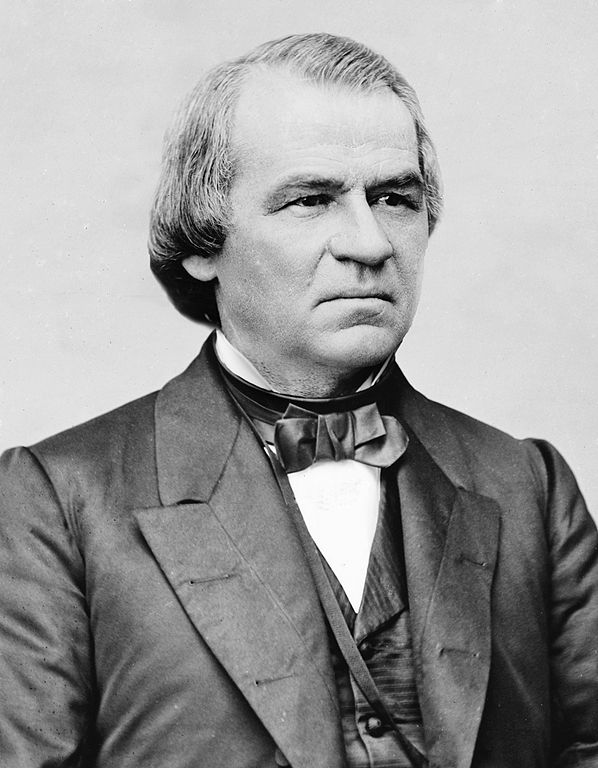

Andrew Johnson, the U.S. president following Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, was critical of Reconstruction. “The subjugation of the states to negro domination will be worse than military despotism,” he wrote in a message to Congress. “The great difference between the two races in physical, mental and moral characteristics is obvious … Of all the dangers our nation has yet encountered, none are equal to the effort now to Africanize the half of our country,” he said in a reference to the southern states.

Johnson’s successor, Ulysses Grant, consolidated Reconstruction, but Rutherford Hayes, the U.S. president from 1977 to 1881, dismantled it. He ordered the withdrawal of federal troops from the south. And in Congress, Democrats passed a bill forbidding soldiers to enforce the laws of the land. The net effect was catastrophic for African Americans.

In 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional, making discrimination in public places legal and opening the way for more Jim Crow laws, which institutionalized racial segregation and disenfranchised blacks.

As Ball writes, “Race segregation (was) made stiff as concrete in ‘places of public accommodation — transport, entertainment, food service, public spaces and parks, shopkeeping and hotels.’

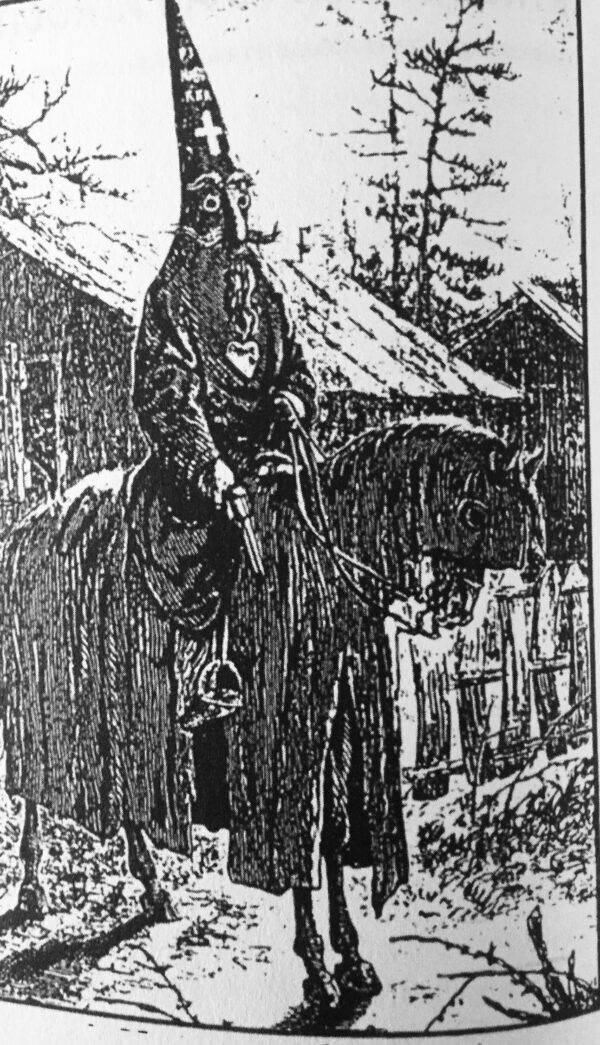

White militias dedicated to suppressing, oppressing and terrorizing African Americans surfaced. Ball theorizes that Lecorgne joined one of these vigilante groups, whose members wore robes and masks or painted their faces with grease or burned cork so as to remain anonymous. “Lecorgne, on a ride into a black village, (was) not a man who (wanted) to be identified by witnesses,” says Ball. But after the passage of the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, which permitted group arrests of vigilantes, he was caught in its web.

As Reconstruction crumbled, some very light-skinned African Americans from the Creole community in Louisiana crossed over into whiteness to survive. “Within each family, people disappeared from one race and joined the other,” says Ball. “No one has counted the number of Louisiana Creoles who passed out of blackness into whiteness, but there were many thousand, and perhaps hundreds of thousands.”

Lecorgne died of malarial fever on October 24, 1886. He was 54. And because he left his wife no assets, she could not afford to buy a proper headstone for him, and he was buried in an unmarked grave.

After his death, the lynching of African Americans became the preferred form of white mob violence, particularly in Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia. And in 1896, the Supreme Court, in Plessy v. Ferguson, sanctified segregation and white supremacy.

From roughly that point forward, the Ku Klux Klan reared its ugly head again, growing into a national movement that waxed and waned according to circumstances.

As Ball suggests, the ideas, notions, tropes and stereotypes promoted by Lecorgne and his ilk run deep in the American psyche.