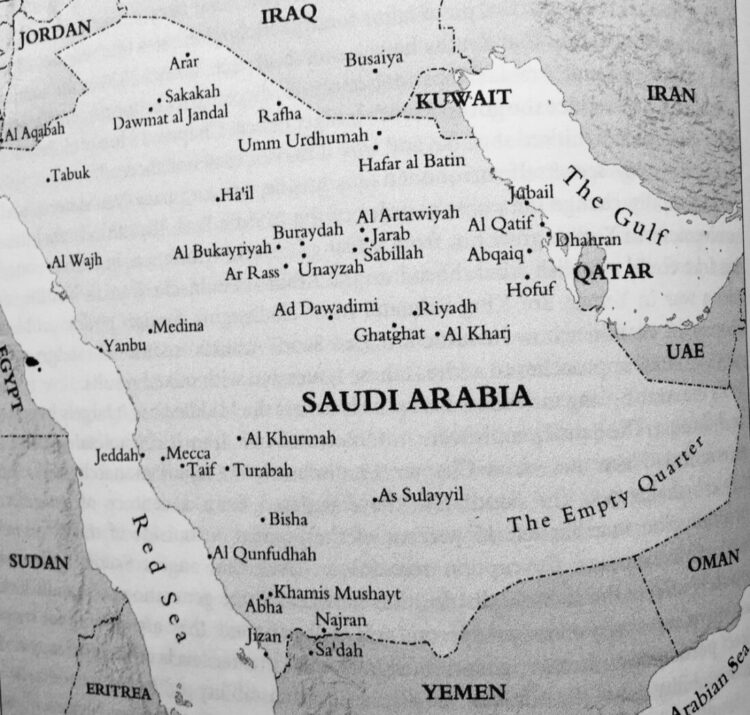

Saudi Arabia, the only country created by and named after a family, the Al Sauds, emerged as a unified state only in 1932, but since then it has established itself as one of the most important nations in the Middle East.

As David Rundell writes in Vision Or Mirage: Saudi Arabia At The Crossroads (I.B. Tauris), much of the global economy relies on stable, predictable Saudi oil production. And without Saudi Arabia, the containment of Iran and a resolution of Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians would be all the more difficult.

In his estimation, Saudi Arabia, the seat of Islam, has entered an unsettled period due to Vision 2030, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s blueprint for its future. It’s a plan that his father, King Salman, supports. Describing it as “the most radical set of economic and social reforms” in half a century, it will affect the balance between tradition and change in the vast theocratic kingdom.

“The king and his son are not trying to make Saudi Arabia more democratic, but they are trying to make it more stable, prosperous, and religiously tolerant,” says Rundell, a retired American diplomat who spent 15 years there. “They have a vision, but will it prove to be a mirage?”

In this first-rate book, he discusses the problems and challenges facing Saudi Arabia, which, until its unification, was as fragmented as Germany or Italy had once been. And in examining these issues, he provides an erudite and sweeping survey of its turbulent history.

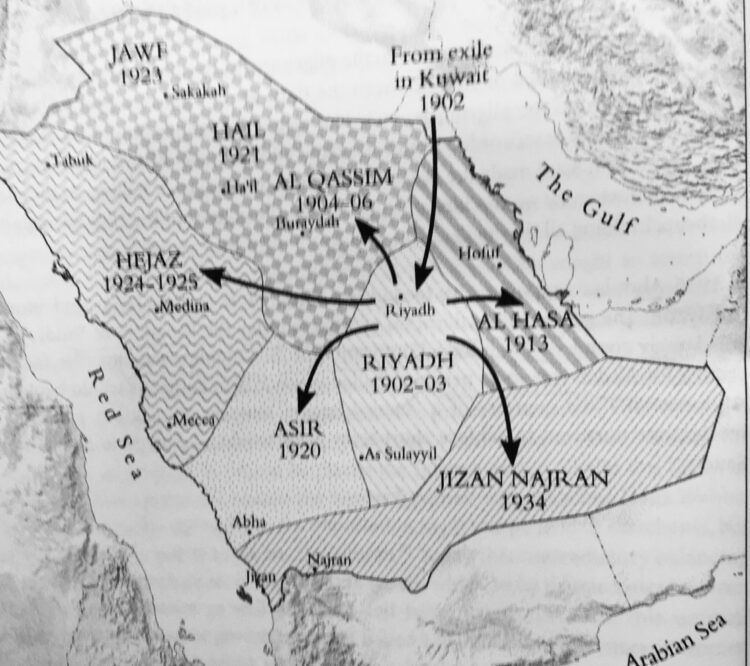

The founder of modern Saudi Arabia, Abdulaziz bin Abd al-Rahman al-Saud (1876-1953), was a descendant of the dynasty’s patriarch, Imam Mohammed al-Saud, who hailed from a village in the Nejd district, whose inhabitants eked out a subsistence living. “They tended date palms, grew grain, dug wells, and prayed for rain,” says Rundell, adding that they also engaged in simple handicraft manufacture and traded with Bedouin tribes for livestock or wool.

Abdulaziz formed an alliance with a zealous religious reformer named Mohammed Abd al-Wahab. It was premised on the understanding that Abdulaziz would provide security, administration and the enforcement of sharia law, while Wahab would be responsible for interpreting his version of an austere and radical Islam. Wahhabism forbids contact with Christians, Jews and even Shi’a Muslims, a minority that has experienced discrimination at the hands of the majority Sunni population.

Intent on expanding the nascent Saudi state, Abdulaziz forged an alliance with the Ikhwan movement, the dominant military force in the Arabian Peninsula. Assisted by Britain, Abdulaziz ousted rivals like Sharif Hussein of Mecca and the Al Rasheed family. Eventually, he would turn against the Ikhwan, which opposed as unIslamic conveniences like cars, radio and telegraph systems. By dint of political savvy, military prowess and British arms, he united the Kingdom of Hejaz and the Sultanate of Nejd to create Saudi Arabia.

Abdulaziz ruled for 51 years, leaving no governing institutions, but transforming a remote, barren and feudal society into a founding member of the United Nations. He was succeeded by one of his sons, Saud, who lived lavishly, fathered 108 children and tolerated graft and corruption.

Though Saud was eventually forced to abdicate, Saudi Arabia has been more successful at managing succession than neighboring states, Rundell observes. “In a region where violent coups and revolutions have been more common than orderly transitions, the Al Saud’s consistent ability to transfer power swiftly and peacefully has contributed to their legitimacy,” he says.

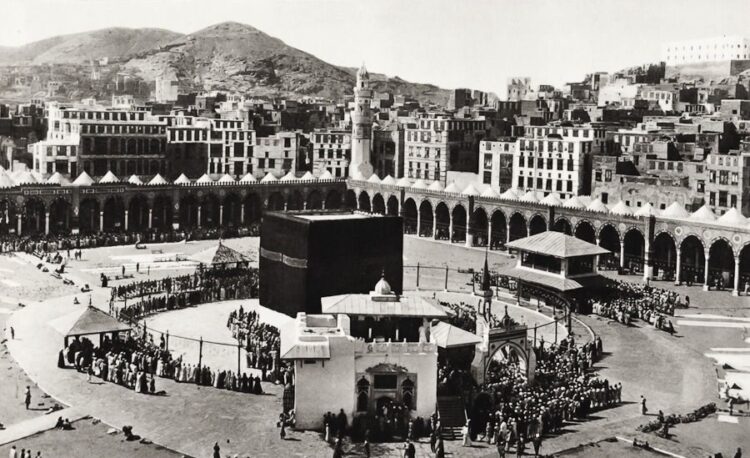

Dissenters have always lurked in the background. In 1979, several hundred Islamic extremists seized the Great Mosque in Mecca, calling for the overthrow of the Saud monarchy and demanding the expulsion of non-Muslims from the country.

The rebels were killed, but the aftershocks of this event were severe. The authorities imposed conservative restrictions on Saudis, closing movie theatres, music stores and mixed-gender swimming pools, cracking down on women’s rights and empowering the religious police to harass women, raid Western compounds and smash photography shops.

During this period, Saudi Arabia began exporting its fundamentalist version of Islam by building mosques and schools across the Muslim world and elsewhere. And a generation of extremists, as exemplified by Osama bin Laden, surfaced, causing untold destruction and chaos in the form of Al Qaeda’s terrorist attack against the United States on September 11, 2001.

With the death of King Abdullah in 2015, Crown Prince Salman assumed the throne, naming his ambitious and impulsive son, Mohammed, as heir apparent. To some, he’s a reformer. To others, he’s an aspiring dictator.

Mohammed and his father benefit from massive oil revenues and Wahhabi doctrines that make political obedience a religious duty. But at the end of the day, the House of Saud must appease key stakeholders — tribes, clerics, merchants, technocrats and members of the royal family itself. “Saudi kings have traditionally consulted these leadership elites to build public consensus before setting policy,” says Rundell.

Saudi kings have traditionally relied on the support of 25 tribes, a few hundred prominent urban families, the religious establishment, the merchant class, the technocrats who administer government ministries and oil fields, and the royals.

Although the House of Saud created the kingdom by force, it has maintained its legitimacy largely through “the principles of consultation and consensus building,” Rundell notes.

Abdulaziz and his successors have recognized that, if they do not lead social change, they will be overtaken by it. Consequently, they have supported gradual social evolution that will satisfy demands for liberalization from an increasingly urban, young and well-educated population, while avoiding a backlash from religious conservatives, who remain potentially violent.

King Salman, however, has abandoned this gradualist approach and has rolled back the religious restrictions imposed after the seizure of the Mecca mosque. Rundell cites the reopening of cinemas, the abolishment of gender segregation in many venues, and the introduction of greater opportunities in the workplace for women.

Still and all, women face significant discrimination. To this day, they need their guardian’s permission to study abroad or marry.

After the maintenance of security, the service that most Saudis expect from their rulers is the improvement of economic conditions. As late as 1960, Saudi life expectancy was only 39, safe drinking water was unavailable, malnutrition was widespread, and fatal diseases were common.

Since then, the health, the education, the housing, and the general welfare of the population has improved markedly. As Rundell writes, “Most Saudis believe that the Al Saud have made their lives better by producing oil efficiently, building high-quality infrastructure, and providing public services at a fraction of their real cost.”

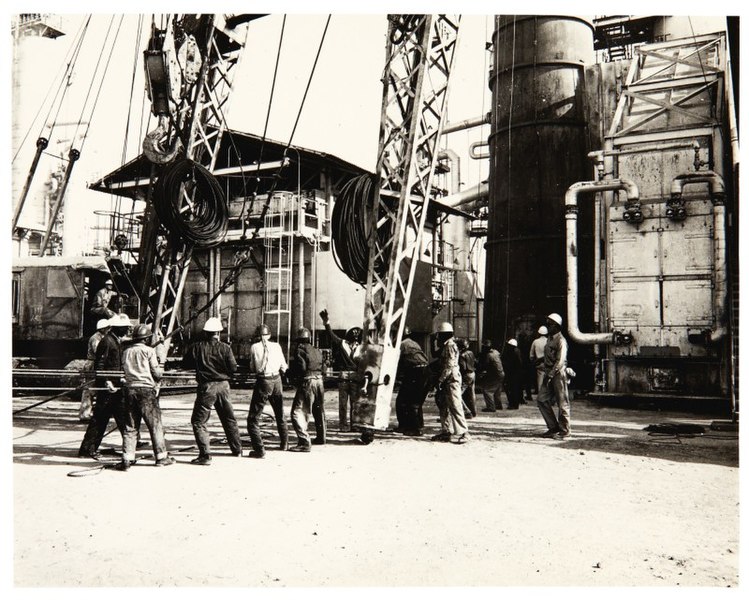

The discovery of oil made all the difference. In 1933, King Abdulaziz invited foreign oil companies, particularly American ones, to bid for concessions. Today, Saudi Arabia is the world’s largest oil exporter, producing 11 percent of the world supplies.

“Oil has allowed a militarily weak state to maintain a global network of dependent customers and appreciative clients,” Rundell says. “Although cooperation with powerful nations underpins Saudi defence policy, it is Riyadh’s ability to influence oil prices and finance its allies that make it worth defending.”

The Saudis have used oil as a foreign policy tool since at least the 1956 Sinai War, during which Israel invaded the Sinai Peninsula. Saudi Arabia also stopped oil shipments during the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

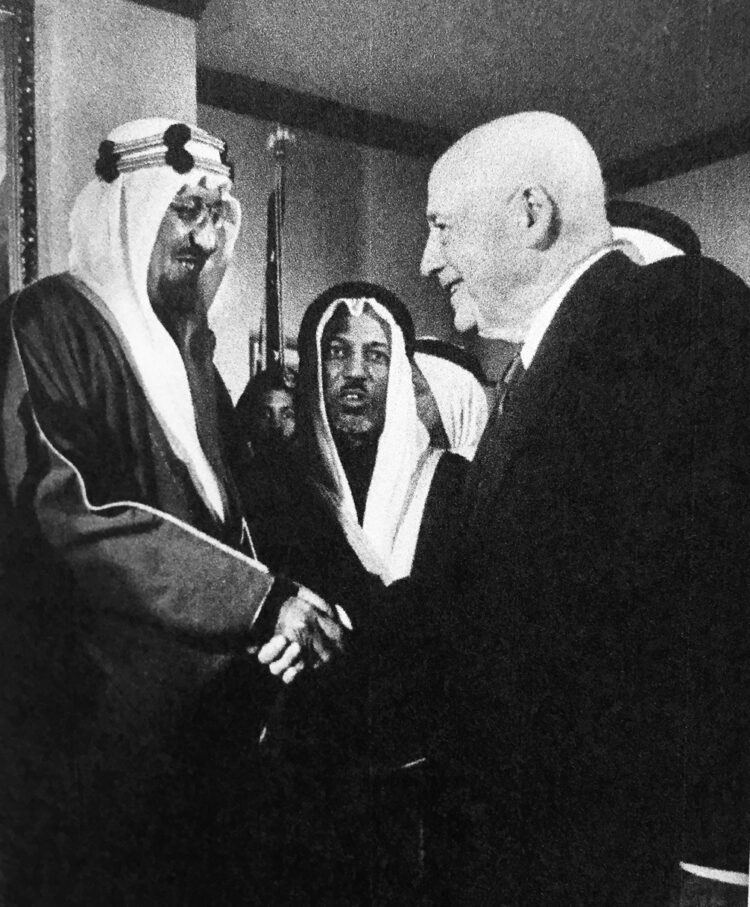

Saudi Arabia has involved itself in the Arab-Israeli conflict since 1945, when King Abdulaziz told President Franklin Roosevelt aboard the USS Quincy that he opposed Jewish statehood in Palestine and that Jews should establish a state in Germany.

Yet, as Rundell points out, Saudi Arabia has never played a significant military role in Arab-Israeli wars. It contributed two companies to the Egyptian army in 1948, a brigade in 1967 that arrived in Jordan only after hostilities had ended, and a brigade that was instructed to stay clear of the fighting in the 1973 war.

“King Abdulaziz was always much more worried about his Hashemite rivals in Jordan and Iraq than about Israel,” he says. “King Faisal often made it clear to American officials that he regarded (Gamal Abdel) Nasser’s Egypt, not the Jewish state, as the greatest threat to his kingdom. In 2020, Saudis are more concerned with Iran than with Israel.”

Saudi Arabia’s obsession with regional stability is such that “anything that disrupts the political and economic status quo — be it Nasser’s brand of Arab nationalism, Bin Laden’s brand of Islam, or an unresolved Arab-Israeli conflict — is a threat to (its) security and prosperity.”

Nevertheless, “nothing has strained the Saudi-American relationship more severely or more consistently than the Arab-Israeli conflict,” he adds.

A keen supporter of the status quo, the House of Saud has always opposed Iran’s efforts to export the Islamic revolution. To the Saudis, Iran’s ultimate objectives are to acquire nuclear weapons, become the region’s dominant military power, challenge their position in oil markets and their role in the Muslim world, and topple the House of Saud.

These are “not unfounded fears,” Rundell warns.

Vision 2030, a plan to convert the Saudi economy into the world’s 15th largest, lays out dozens of initiatives and is intended to lessen reliance on oil extraction. But as Rundell says, Vision 2030 is a paradox, having phased in disruptive economic and social reform to preserve a traditional monarchy.

Rundell believes that, under King Salman and his son, Saudi Arabia has become more autocratic. For example, nascent participatory institutions, such as elected municipal councils, have been marginalized. “Civil liberties, which were never prominent, have become even more restricted,” he notes.

Meanwhile, opponents of Crown Prince Mohammed have been intimidated or killed. “There is clearly a tension between (his) modernizing agenda and his authoritarian means of achieving it. In the short run, that may be unavoidable. In the long run, it is likely to be unsustainable.”

Rundell acknowledges that, while reform may well foster Saudi stability, it could destabilize the country. “Across Saudi society, the reshaping of social and economic norms has weakened elite cohesion as well as the patronage networks that the Al Saud relied on to monitor and alleviate dissent,” he says.

Saudis may be in for a rough ride.