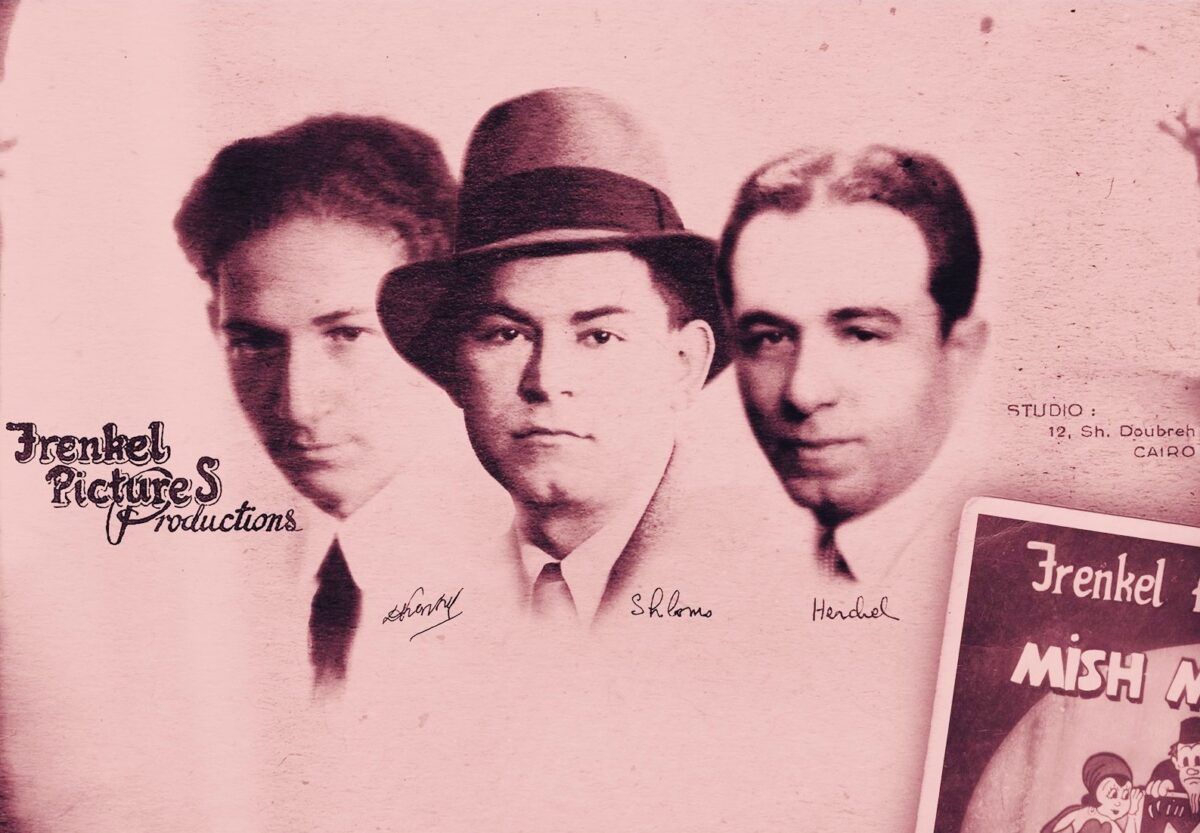

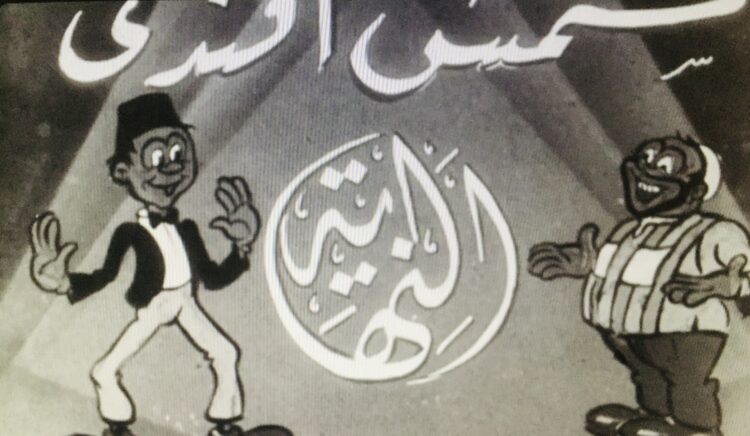

David, Herschel and Salamon (Shlomo) Frenkel were pioneers in the truest sense of the word. They were the first filmmakers to bring the art of the animated cartoon movie to Egypt. Active in their adopted homeland from the mid-1930s until the early 1950s, the Frenkels created Misha-Mish Effendi, the Egyptian equivalent of Mickey Mouse.

With the birth of Israel, the upsurge of Arab nationalism and the emergence of the Arab-Israeli conflict, Jews in Egypt felt increasingly uncomfortable and came under intense local pressure to emigrate. Affected by these developments, the Frenkels immigrated to France, leaving behind a unique cinematic legacy, which was repressed by the Egyptian government and all but forgotten by Egyptians.

Tal Michael’s intriguing documentary, Mish-Mish, lovingly resurrects this lost era. It will be screened at the forthcoming Hannukah Film Festival, which will be presented online by Menemsha Films from November 28 to December 5.

The Frenkels, Ashkenazic Jews from Russia, arrived in Egypt — the first Arab country to establish a national film industry — during World War I. Having fled pogroms in Russia, they settled in Jaffa, a mainly Palestinian Arab town in Ottoman Palestine.

Accused by the Turkish authorities of being Russian spies, the Frenkel family immigrated to Egypt, then a British colonial protectorate. They set down roots in the coastal city of Alexandria, a cosmopolitan center of Egyptian and European culture immortalized by Lawrence Durrell in his four novels, The Alexandria Quartet.

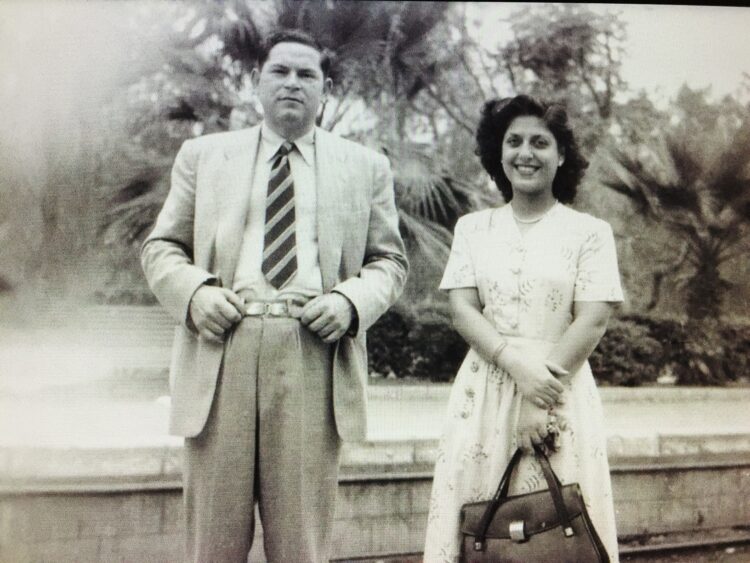

Herschel (1902-1972), Salamon (1912-2001) and David (1914-1994), being cinephiles, formed Frenkel Pictures in Cairo. In a division of labor, David was the idea man and artist, Salamon was the technician, and Herschel was the distributor. They worked in harmony, like “fingers joined by the palm of the hand.”

Michael’s film begins in a what appears to be a suburb of or a town near Paris. Didier, Salamon’s son, is busy rummaging through dusty film canisters his father and two uncles brought from Egypt. Salamon wanted to throw them out, but Didier kept them in his basement.

To Didier, their films are priceless treasures, celluloid relics from a past his mother, Marcelle, equates with deprivation and suffering. Intent on preserving the reels, Didier called the National Institute of Cinema, whose experts agreed to restore them to their original clarity and beauty.

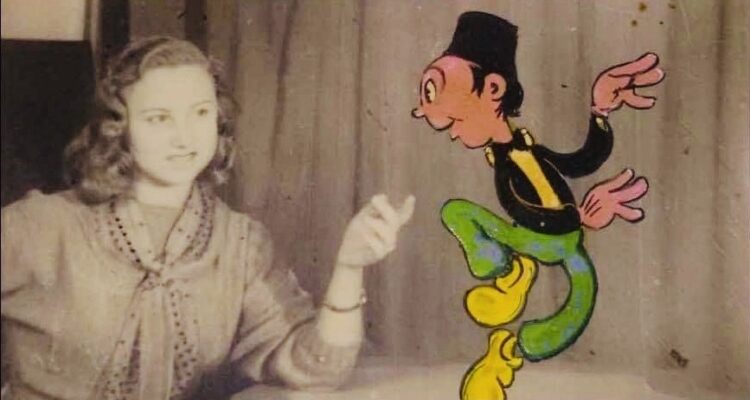

Influenced by Walt Disney and financed by well-to-do backers, the Frenkels created their first black-and-white animated movie, It’s Useless, in 1936. Eventually, they churned out live action films in which famous actresses of the day appeared, as well as commercials and propaganda movies for the Egyptian government.

The brothers were perfectionists. If something was amiss, they would not hesitate to scrap the footage and start again.

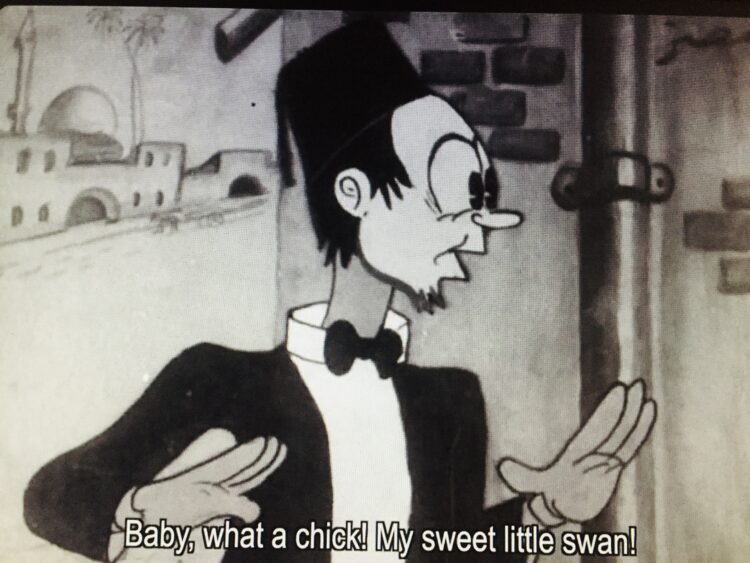

Their greatest achievement, Mish-Mish Effendi, was a happy-go-lucky character beloved by audiences. Since Michael does not delve deeply into the Frenkel’s operation, a viewer never learns whether their films were profitable or exported to neighboring Arab countries. Nor do we know whether the Frenkels were Egyptian citizens. They may have been stateless, like some Jews in Egypt. These are among the yawning gaps in Michael’s otherwise interesting narrative.

We are told, however, that the Frenkels were on the cusp of fame and fortune when fate intervened and cruelly dashed their dreams. This is a reference, of course, to the untenable position Egyptian Jews found themselves after Israel declared statehood and Egypt joined the pan-Arab military effort to wipe it out.

Marcelle, a Sephardi Jew, alludes to these tensions and difficulties, but offers no elaboration. Regrettably, Michael merely glosses over them, too, refraining from fleshing out important or telling details.

The long and short of it is that the Frenkels decided they could no longer live in a hostile environment in Egypt. Like the vast majority of Jews, they left the country they loved. Marcelle hoped to join her brothers in Israel, but the Frenkels balked, assuming that Israel would not suit their purposes.

From a professional perspective, France turned out to be a disappointment for the Frenkels. Mimiche, the French version of Mish-Mish, did not catch on. And their animated movies, particularly The Beautiful Blue Danube, flopped.

In Egypt, meanwhile, the Frenkels were consigned to the dustbin of history, while their native son Egyptian competitors got all the credit for the establishment of a local animated cartoon industry.

Of late, the Frenkel brothers and their body of work have been rediscovered by a new generation of Egyptian movie fans. It would appear that Mish-Mish has arisen from the ashes and been reborn.

For further information on the festival: https://www.menemshafilms.com/hanukkahff2021