Testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on March 20, 1981, U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig said the Reagan administration was trying to build a “strategic consensus” to counter the influence of the Soviet Union, its chief global adversary, in a region encompassing countries from Pakistan to Egypt.

Claiming that the Soviet Union was a serious threat to their national interests and that it would be to their advantage to cooperate with the United States, Haig urged regional rivals like Israel and Saudi Arabia to set aside their differences so that this objective could be achieved.

“We feel it is fundamentally important to begin to develop a consensus of strategic concerns throughout the region among Arab and Jew, ” he said.

Israel endorsed Haig’s call for unity in the face of Soviet encroachments in the Middle East, but the Arab world rejected it. Not a single Arab or Muslim state embraced his idea, notwithstanding the fact that Egypt had signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979 and that Jordan would follow suit in 1994.

Nearly four decades on, Haig’s visionary concept is winning new recruits and gaining ground.

Last year, thanks to the intervention of the Trump administration, four Arab states — the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco — agreed to normalize relations with Israel under the umbrella of the Abraham accords.

Today, the enemy is not the Soviet Union, which collapsed and gave way to Russia, but Iran, the preeminent Shi’a power in the Middle East.

Iran’s hegemonic ambitions and its quest for a nuclear arsenal have rattled Sunni Arab states from the Persian Gulf to the Atlantic Ocean and driven them to accept Israel’s existence, if not its legitimacy.

Trump’s successor, Joe Biden, has promised to extend the Abraham accords, though he knows that some Arab states will not cooperate until the Palestinian question is resolved by means of a two-state solution.

In the meantime, two of the Arab countries that have have begun to normalize their relations with Israel — Morocco and the United Arab Emirates — have broaden them even further of late.

Several days ago, Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz visited Rabat, the capital of Morocco, and signed a memorandum of understanding with his Moroccan counterpart, Abdellatif Loudiyi.

“We have signed an agreement for military cooperation — with all that that implies — with Morocco,” said Gantz, who also met the chief of staff of the Moroccan armed forces, Abdelfattah Louarak. “This is a highly significant event that will allow us to enter into joint projects and allow Israeli (defence) exports.”

Regarded as the first Israeli agreement of its kind with an Arab state, it is expected to facilitate intelligence cooperation, joint military exercises, and the sale of Israeli weapons to Morocco. According to observers, Morocco requires unmanned aerial vehicles and air defence systems.

“This agreement will allow us to cooperate, with exercises and with information, and allow us to assist them with whatever they need from us, in accordance, of course, with our own interests,” said Zohar Palti, a senior Israeli official who accompanied Gantz to Rabat.

Morocco severed diplomatic relations with Iran in 2018 after accusing Tehran of backing the Polisario movement, whose goal is to achieve independence in the disputed Western Sahara.

“We are in the midst of … one of the high points of the Abraham accords,” added Palti, the director of the Ministry of Defence’s Political-Military Bureau. “A plane carrying an (Israeli) military delegation, including soldiers in uniform and a defence minister who lands in Rabat openly and meets with the military and diplomatic leadership of Morocco — the foreign minister, the defence minister, the head of the intelligence service, the chief of staff. This is an event we have never seen before.”

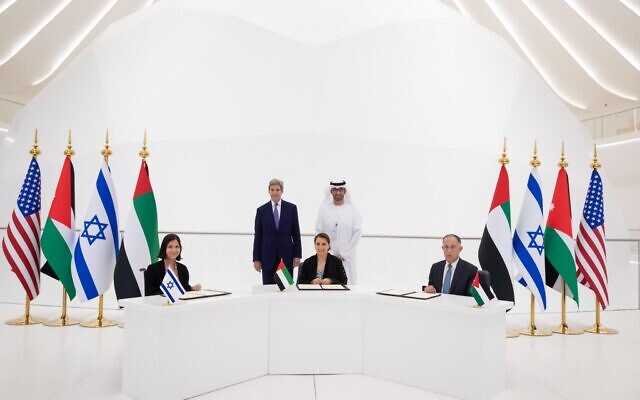

Two days before Gantz’s visit unfolded, Israel and Jordan signed the largest cooperation agreement in the history of their bilateral relations. It was brokered by the United Arab Emirates and supported by the United States.

Under the deal, Israel will send 200 million cubic meters of water to Jordan from a desalination plant on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea, while Jordan will supply solar power to Israel from a facility to be built by the United Arab Emirates.

The idea was hatched two months ago during a meeting between Israeli Energy Minister Karine Elharrar and the United Arab Emirates’ ambassador to Israel, Mohammed al-Khaja.

“The benefit of this agreement is not only in the form of green electricity or desalinated water,” said Elharrar, “but also in the strengthening of relations with a neighbor that has the longest border with Israel.”

The agreement comes in the wake of Israel’s recent decision to sell 50 million cubic meters of water a year to Jordan, twice as much as it already supplies, and to permit Jordan to increase its exports to the West Bank.

These accords are bound to improve Israel’s sometimes rocky relationship with Jordan, which floundered in the waning years of Benjamin Netanyahu’s premiership, though it will not soften the attitude of Jordanians who look askance at Israel.

That the United Arab Emirates will play a key role in Israel’s agreement with Jordan is hardly surprising. In the past two months, the United Arab Emirates has significantly enhanced its burgeoning ties with Israel.

On November 16, Israeli and Emirati defence companies signed two agreements to jointly develop remote-controlled and autonomous vehicles and to sell advanced cameras for commercial and military purposes.

On November 11, the navies of the United States, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain launched an exercise in the Red Sea.

On October 25, the commander of the United Arab Emirates’ air force, General Ibrahim Nasser Mohammed al-Alawi, visited Israel as guest of General Amikam Norkin, the commander of the Israeli Air Force.

Currently, Israel and the United Arab Emirates are working on a free trade agreement. Since 2020, their volume of trade has reached $600.

Amid these developments, Israel’s relationship with Egypt has improved markedly in the past few years. This policy is being pursued by Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who seized power in a coup in 2013 after deposing his predecessor, Mohammed Morsi, a member of now-banned Muslim Brotherhood.

Recently, Sisi hosted Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett at what appears to have been a successful summit in Sharm el-Sheikh in the Sinai Peninsula.

Shortly after their meeting, senior Israeli and Egyptian army officers conferred there to discuss a request by Egypt to bolster its military garrison in Sinai, from which Israel withdrew in 1982.

Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt, signed by Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, limits the number of Egyptian troops who may be deployed in Sinai. But since the outbreak of an Islamic State rebellion there, Israel has allowed Egypt to more than double its armed presence in the peninsula.

Two years ago, Sisi admitted that Egypt’s security cooperation with Israel is “tighter” than it has ever been.

The two countries share a common enemy in Islamic State and Hamas, a branch of the Muslim Brotherhood that has ruled the Gaza Strip since 2006. Like Israel, Egypt has imposed a blockade on Gaza.

In most other respects, though, Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt is decidedly cold. There are no cultural, educational or scientific exchanges. Very few Egyptian tourists visit Israel. And on the grassroots level, anti-Israel feeling runs deep.

Yet strategically speaking, Israel and Egypt are on the same page, at least for now, in line with Haig’s concept of “strategic consensus.”