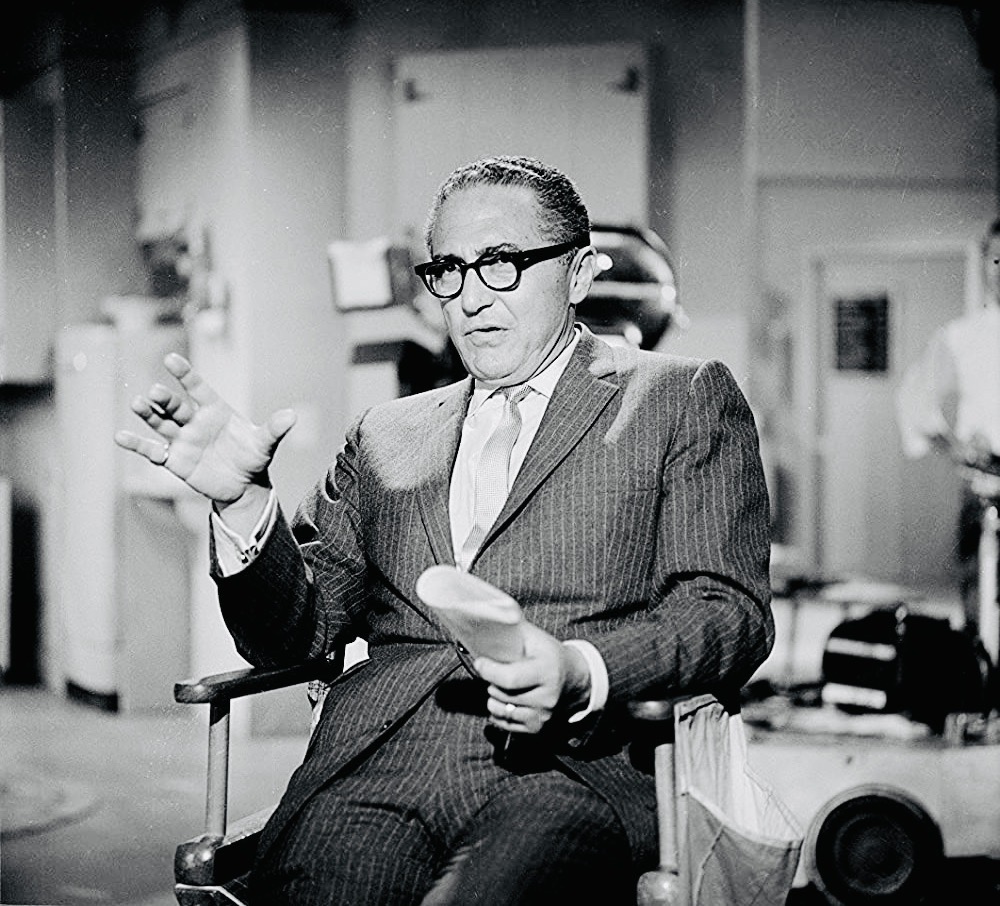

Sheldon Leonard was a Renaissance Man in the highly competitive business of show business, moving seamlessly between theater, radio, film and television. He appeared in Broadway plays, starred in Hollywood movies, churned out radio scripts, and produced TV sitcoms.

Leonard’s contributions to middlebrow American culture are highlighted in Allan Holzman’s breezy documentary, Sheldon Leonard’s Wonderful Life, which is currently being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation.

Holzman’s 52-minute film glosses over the surface, never pausing to examine any facet of his life in depth. Virtually ignoring Leonard’s stint as a theater actor, he merely dances around his career in radio. He spends more time delving into his involvement in the film industry.

Born in New York City’s Lower East Side in 1907, he anglicized his birth name, Shalom Lieb Bershad, to Sheldon Leonard when he was a young man, realizing that his ambition to be an entertainer in the first half of the 20th century required him to jettison part of his Jewish identity.

From the late 1930s onward, Leonard — a graduate of Syracuse University — was cast in minor roles in scores of mostly now-forgotten movies, some of which can be viewed on the Turner Movie channel. He usually portrayed gangsters, shysters and ne’er-do-wells in pictures such as The Thin Man and To Have And To Have Not. But in the 1946 classic, It’s A Wonderful Life, he played a barman offering sage advice to a character played by Jimmy Stewart.

Starting in the early 1950s, Leonard sold scripts to the new television medium, which was desperately short of material. His scripts were mangled, prompting him to become a producer.

Blessed with a sharp eye for a compelling story line, and ready to pay big bucks for the finest actors and writers, he was successful in this new endeavor, turning out memorable sitcoms like The Andy Griffith Show and The Dick Van Dyke Show.

It was Leonard’s idea to cast Griffith as a sheriff and mayor in small-town America. In truth, Griffith was not keen on playing a hayseed, but his faith in Leonard’s judgment was a such that he overcame his reservations.

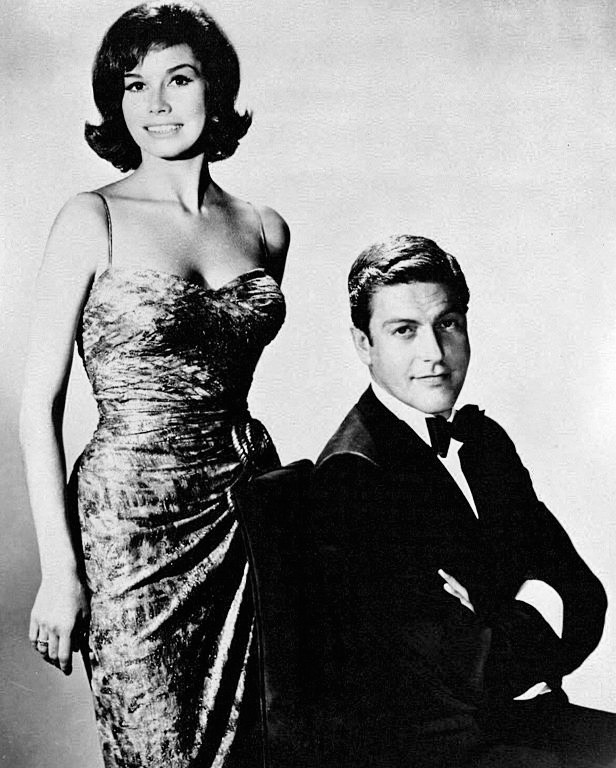

Leonard struck gold when he cast the fetching Mary Tyler Moore in The Dick Van Dyke Show. She was a versatile performer who could act and dance and exude a combination of sex appeal and warmth.

Leonard’s next venture, I Spy, broke a long-established barrier when he hired Bill Cosby, an African American, as one of the co-stars alongside Robert Culp. The TV networks were “very apprehensive” about hiring Cosby, fearing that a Southern audience would be antagonized. Leonard persevered, convincing the president of one network to cast Cosby.

“The whole history of television changed at that moment,” says Leonard, looking back with satisfaction.

I Spy was unique for another reason. It was the first major television show to be shot in foreign locales. Its exoticism was definitely a plus, burnishing Leonard’s reputation as an innovator.