With sadness and resignation, I regret to say that the world’s oldest and most durable hatred is burning bright yet again.

Reports released in recent days by Tel Aviv University’s Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry, the Anti-Defamation League in the United States, and B’nai Brith in Canada point in only one disconcerting direction.

On the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day, antisemitic incidents reached record levels, spurred on by classic anti-Jewish tropes and stereotypes, the coronavirus pandemic, and Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians.

Antisemitism was thrown into disrepute in the immediate wake of the Nazi mass murder of European Jews during World War II. Antisemites kept a low profile during this relatively brief period. But as the shock of the Holocaust gradually wore off and as the images of Nazi concentration camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau incrementally faded, the Jew haters were back in business again, like vermin crawling out of the woodwork.

Their reemergence confirmed an old and reliable truth — antisemitism never dies, it merely hibernates until the next vicious wave. Antisemitism is a recurring and pathological phenomenon that confronts every Jewish generation.

It’s a malignant growth that ultimately defies treatment. It occurs primarily in Christian and Muslim societies. And while it’s usually embraced by a vociferous minority, its tentacles often reach beyond that hardbitten core. It affects the working-class, the middle-class, and the elite. It exerts an influence on the educated and the ignorant alike. It seeps into right-wing and left-wing discourses. It insinuates itself into advanced and underdeveloped countries.

In some cases, antisemitism is promoted by relatively mainstream governments. “Notes from Poland,” a blog that tracks Polish developments, published a piece on April 25 claiming that a nationalist media group, Magna Polonia, received funding from the current right-wing Polish government to print an antisemitic book that condemns Jews as a “parasitic tribe.” The volume in question, Meet the Jew, was originally published in 1912 and was written by Teodor Jeske-Choinski.

A report issued by Tel Aviv University on April 27 paints a grim picture of the persistence of antisemitism.

Some snapshots of this malignancy in 2021.

Antisemitic attacks in Germany, the incubator of the Nazi movement and of genocidal antisemitism, reached its highest level in years.

Such assaults almost doubled in Britain, the first country to expel Jews en masse, and more than tripled in France, which spawned the notorious Dreyfus affair and the collaborationist Vichy regime.

The Covid-19 pandemic and Israel’s cross-border war with Hamas were among the catalysts that fired up antisemitism last year.

Antisemites and their fellow travellers claimed that Jews were involved in the spread of the deadly disease and profited by it.

Albert Bourla, the chief executive officer of the Pfizer drug company, was cited as an offender. In Greece, Bourla’s birthplace, a far-right rag published a photograph of him alongside Joseph Mengele, the German physician who selected newly-arrived Jews to be gassed at Auschwitz and who conducted gruesome medical experiments on Jewish inmates.

The fourth war pitting Israel against Hamas aroused rage among Palestinians and their supporters outside the Middle East. Hotheads among them assaulted Jews in the Diaspora, confirming the thesis that anti-Zionism and antisemitism merge into perfect symmetry during a crisis.

There is nothing new here. From the birth of Israel onward, Jews in Arab lands were maligned, marginalized, imprisoned, persecuted and driven out of their homes in countries ranging from Egypt and Syria to Libya and Yemen.

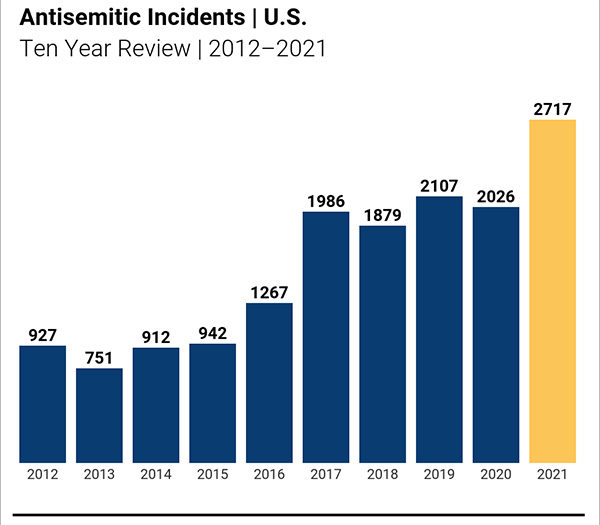

Yet, as the Anti-Defamation League reports, antisemitism rears its head even in the most tolerant of nations. In the United States last year, the number of recorded antisemitic incidents rose to a new height of 2,717, representing a 34 percent increase over the previous year.

There is no single cause for this spike, according to Jonathan Greenblatt, the chief executive officer of the Anti-Defamation League. “But we do know that Jews are experiencing more antisemitic incidents than we have had in this country in at least 40 years,” he said in its annual report.

By his reckoning, political instability and polarization are two of the drivers of antisemitism.

There is a silver lining in the dark clouds. For the second consecutive year, not a single American Jew was killed during an antisemitic incident.

Jews in Canada have not been murdered in antisemitic attacks, but in 2021, B’nai Brith says, there were 2,799 anti-Jewish hate crimes, a seven percent increase from the year before. These crimes encompassed beatings, vandalism of synagogues and swastika daubings in schools. The majority of victims appear to have been Orthodox Jews.

“If you are Jewish, you are more likely to be a victim of a hate crime by far than if you are a member of another minority,” says B’nai Brith’s senior legal counsel, David Matas.

Melissa Lantsman, a Conservative Party member of Parliament who represents the greater Toronto riding of Thornhill, believes that Canada is experiencing a “rising tide” of antisemitism.

Taken together, the upsurge of antisemitism around the globe should be an admission that efforts to minimize it or nip it in the bud have failed miserably, notwithstanding the extensive resources that have been poured into its containment or eradication.

Antisemitism has festered for centuries, rising and falling in cycles, but it has never disappeared. This is the sobering lesson to be learned by optimists who believe it can be reined in or stamped out.