Winnipeg, in my imagination, is virtually terra incognita, a Canadian city on the prairies known for its bitterly cold winters and sweltering summers.

What I actually know about Winnipeg is factual.

Three decades ago, I found myself in Winnipeg in January, the coldest month of the year. What I mostly remember now is the extreme sub-zero weather that kept me off the streets.

During the 1980s, my boss was Maurice Lucow, a newspaperman born and bred in Winnipeg. Occasionally, he would reminisce, recalling his birthplace with a certain fondness.

Bill Davies, the writer and director of The Jews of Winnipeg, a 27-minute National Film Board of Canada documentary, offers a different perspective of one of Canada’s largest metropolitan centers. Released in 1973, it is being streamed online, free of charge, during Canadian Jewish Heritage Month (nfb.ca) in May.

With a few broad brushstrokes, Davies glides over the history of Jewish settlement in Winnipeg. It’s an interesting snapshot of a close-knit community at a particular moment in time.

As the film begins, he mentions two people, Sol Kanee and Samuel Freedman, who are synonymous with the city’s growth and development.

Kanee, a member of the board of governors of the Bank of Canada and of the University of Manitoba, was the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress from 1971 to 1974. Freedman was the Chief Justice of the Manitoba Court of Appeal.

Their ancestors were Jewish refugees who arrived in Winnipeg from the Russian empire in two waves.

Jewish artisans, workers and shopkeepers settled in Winnipeg following the Russian pogroms of 1882. Some worked as laborers for the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Still others took up farming before branching into itinerant peddling. And as Davies observes, Jews shared in the prosperity of the 1890s.

The failed 1905 revolution in Russia brought a fresh group of Jewish immigrants to Winnipeg, some of whom were Marxists raised in the tradition of Jewish radicalism.

Davies interviews Joseph Zuken, a descendant of one of these newcomers. From 1961 to 1983, he was the only communist municipal councilman in North America. According to Zuken, his ancestors were driven by a passion for education and social justice. They participated in the 1919 Winnipeg general strike, which was broken up by the RCMP and claimed the life of one protester.

The working-class Jews of that bygone era are a thing of the past, Davies says. Yet 7,000 out of 20,000 Jews in Winnipeg still speak Yiddish, he adds.

Davies goes on to say that the hardcore antisemitism that afflicted Jews in Canada before World War II is virtually gone, enabling Jewish Canadians to contribute freely and creatively to the arts and sciences.

No longer do Jews face quotas in, say, medical schools or law firms. And restrictive covenants, which once prevented Jews from buying homes in choice Winnipeg neighborhoods like Tuxedo, have vanished.

Davies gives us a brief tour of Winnipeg’s north end district, where the majority of Jews used to live. The camera pans on Oscar’s Delicatessen, a favorite gathering place, and Gunn’s, a bakery renowned for its breads, bagels and pastries.

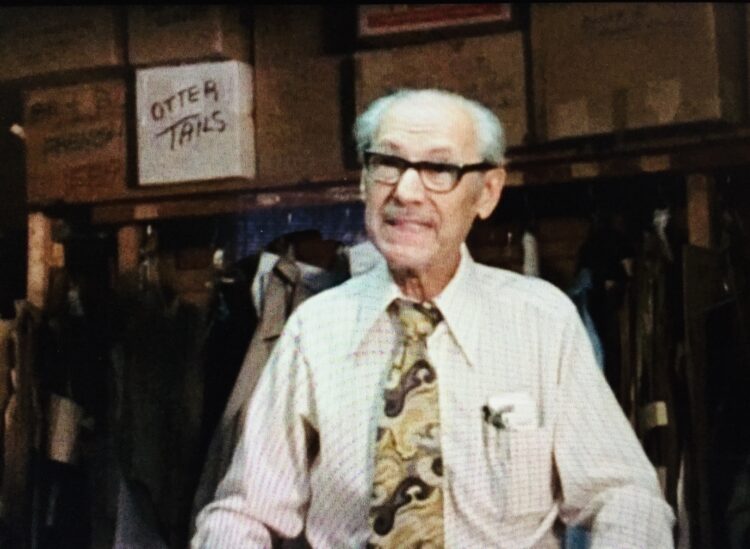

Sid Gitterman, the owner of a fur shop, expresses regret that the father/son partnership in Winnipeg’s needle trade has disappeared.

David Steinberg, a graduate of Winnipeg’s Talmud Torah, speaks briefly about his boyhood. Since leaving the city, he has made a name for himself in the American entertainment industry as a comedian and as a director of Curb Your Enthusiasm, an immensely popular television show.

Davies ends the film on an upbeat note. He quotes an elderly Jewish resident of Winnipeg as saying that he feels fortunate to be a citizen of a country where freedom, liberty and tolerance are valued.