European Jews on a fairly considerable scale drifted into the visual arts world as collectors and dealers in the 19th century and became, against all odds, arbiters of taste. Once regarded as outsiders on the margins of high culture, they were suddenly thrust into positions of prestige and influence.

Charles Dellheim, a professor of history at Boston University, charts their entry into this field in his masterful and magisterial book, Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made The Art World Modern, published by Brandeis University Press.

As he points out, the patronage of the arts was traditionally the preserve of the aristocracy, while the collection and the display of fine paintings were reserved for exalted and wealthy persons. “The ability to discuss pictures intelligently was an essential quality of a true gentleman,” he notes.

But as the old order crumbled, forcing landed aristocrats to sell off old master paintings, sculptures and objets d’art, Jews pivoted toward the art business. It was, as he observes, a “good fit” because Jews were a “classic middlemen minority who mediated between producers and consumers in different settings.”

Jews largely gravitated toward art because, for among other reasons, it required a modest capital investment and offered geographical mobility. “Art dealing and collecting furnished a means of acculturation, a source of wealth and a mark of status,” he writes.

Yet the growing prominence of Jews in this milieu unleashed antisemitic hatred and a toxic response from Nazi Germany. “Fine art, therefore, became a bloody crossroads where culture and money, aesthetics and avarice collided with disastrous consequences,” he adds.

According to Dellheim, the first forays of Jews into the art market took place in 17th century Amsterdam, a fairly tolerant city by the standards of the day. “But it was in the German-speaking world of Mitteleuropa that Jews began to have a strong impact on buying and selling art,” he says.

Nathan Wildenstein, a horse dealer and a textile merchant from France, was one of the first 19th century Jews to transition into art. He established an art gallery that regularly exhibited old masters, which he sold to commoners as well as nobles. One of his descendants, Georges, opened galleries in New York City, London and Buenos Aires in the first half of the 20th century.

Henry Duveen, a Dutch immigrant, penetrated the American and British art markets and was close to the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.

Ernest Gimpel helped the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to acquire major masters. His son, Rene, sold paintings to “Our Crowd” German Jews like the Schiffs and the Warburgs.

Rudolph Kann and his brother, Maurice, assembled the finest private art collection in Paris.

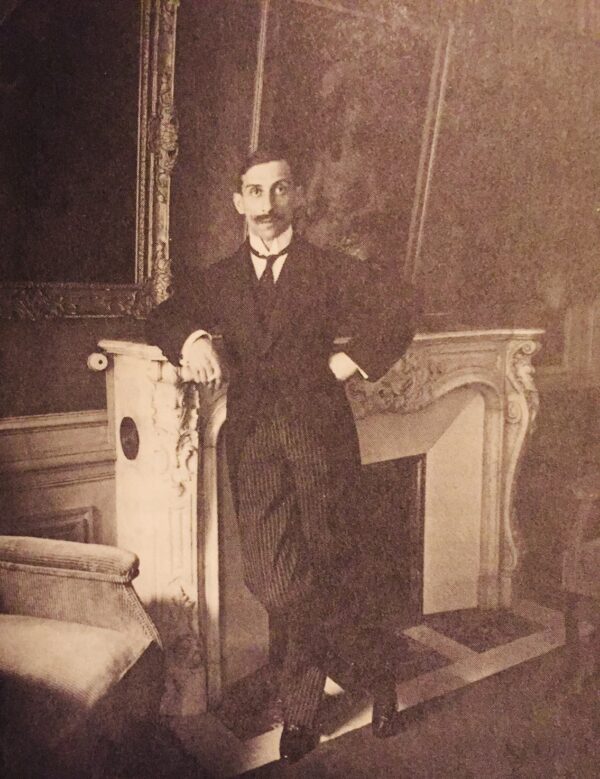

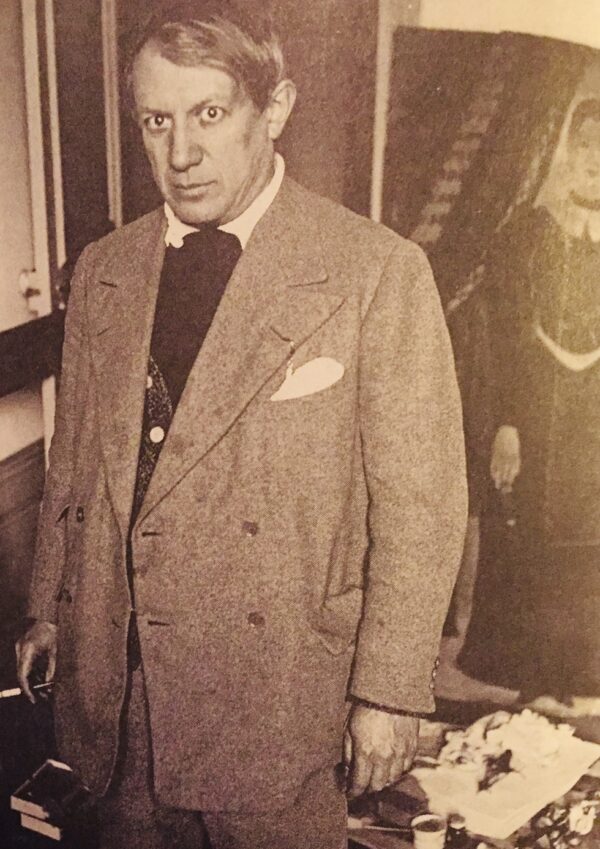

Alexandre Rosenberg, originally from Slovakia, began by selling mainly antiques before branching into fine art. His two sons, Leonce and Paul, took over the business. Paul formed an excellent relationship with Pablo Picasso, as did Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. In New York, Paul opened a gallery specializing in 19th and 20th century French paintings.

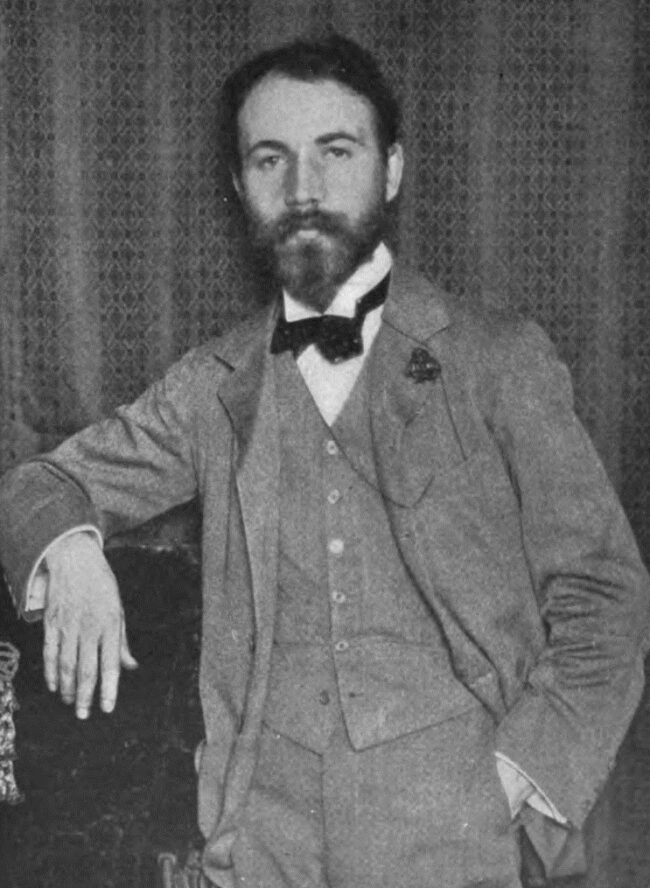

Alexandre Bernheim was one of a handful of dealers who recognized the importance of impressionism. His sons, Josse and Gaston, mounted major exhibitions on heretofore neglected painters such as Van Gogh and Cezanne.

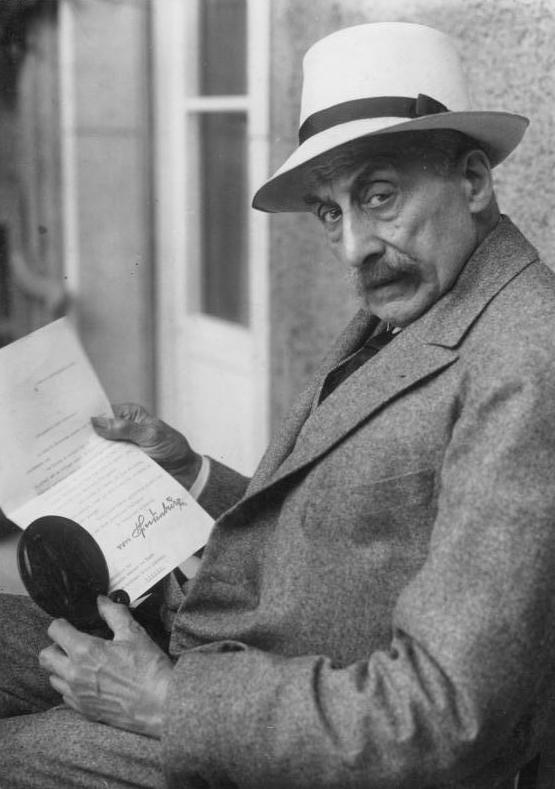

Bernard Berenson, the great art scholar, was born in a Lithuanian shtetl near Vilna. He and his family immigrated to the United States in 1875 when he was 10 years old. A brilliant student, he studied art history at Harvard University. In 1891, he converted to Christianity, assuming his new religion would be his admission ticket to academia. Around 1907, he started providing letters of certification for the Duveens. He spent his final years in Italy, a fixture in Italian high culture even after the ascent of the fascists.

By Dellheim’s reckoning, the 1920s and 1930s were the high-water mark of the prominence of Jews in art as artists, dealers, collectors, critics and historians. There was a downside, of course. As he puts it, “Visibility exacerbated vulnerability: the belief that artful Jews had amassed untold stores of fine art by dubious or dishonest means became fodder in the antisemitic arsenal.”

For example: In a series of articles in the Parisian daily Le Figaro, the right-wing art critic Camille Mauclair denounced Jews, blaming them for France’s ills.

And in Nazi-era Germany, Jewish painters such as Marc Chagall and Max Liebermann, the president of the Prussian Academy of Art, were equated with the pitfalls of modernity.

The Nazis were completely contemptuous of Jewish artists and critics, claiming that they were materialists who lacked an aesthetic sense. Describing the Nazi attitude, Dellheim writes, “Beauty was beyond them. All they could do was acquire and possess works of art they could never begin to appreciate and certainly did not deserve.”

Jewish painters, naturally, were among the practitioners of “degenerate” art the Nazi regime regularly denounced.

During the Nazi occupation of France, Germany stripped Jewish-owned galleries of their fabulous treasures. This grand theft was entrusted to the German ambassador in Paris, Otto Abetz. As the Allies stormed into France, the Germans loaded their ill-gotten gains on trains bound for Germany.

With skyrocketing prices for certain paintings, Jewish survivors and their heirs pressed for the return of their looted works of art. It was not until the 1990s that Nazi-stolen art morphed into a public issue, and this is where it remains today.

Dellheim has written a highly readable, substantive and engaging account of the entry of Jews into art. It may well be the definitive work on this topic.