The Jewish citizens of the Scandinavian nations of Sweden, Norway and Denmark had very different experiences during the Holocaust, as Suzannah Warlick’s documentary, Passage to Sweden, attests.

The film will be screened at this year’s Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 9-26.

As Warlick points out, Sweden enjoyed immunity from the tumult of World War II. Germany respected its neutrality for at least two reasons. The Nazi regime needed Sweden’s steady supply of iron ore, which was essential in the manufacture of weapons. And Germany valued Sweden’s access to the sea, which was important in terms of trade.

Consequently, Sweden’s relatively small Jewish community was protected. “We were spared the horrors of war,” says Chana Sharftstein, whose father was the chief rabbi of Sweden. “We lived in the midst of hell, but our lives were normal.”

Norwegian and Danish Jews were not as fortunate. They faced danger following Germany’s invasion of Norway and Denmark on April 9, 1940.

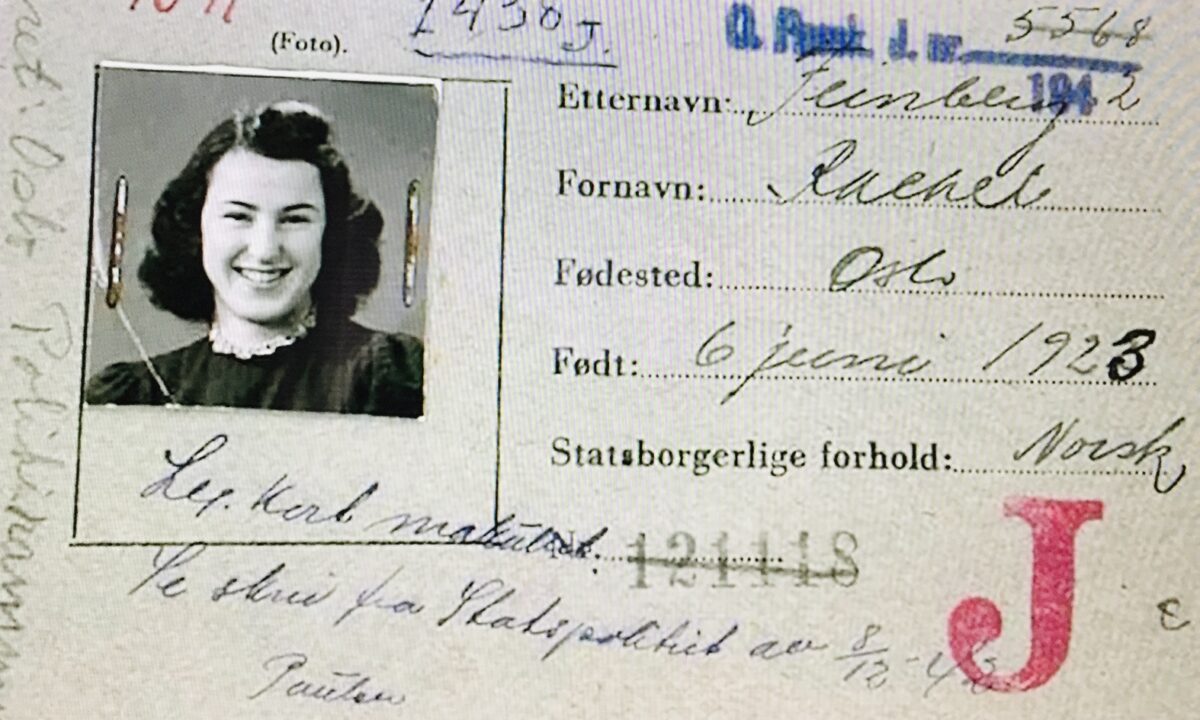

In Norway, the collaborationist Quisling government cooperated with the Germans in demonizing, persecuting and deporting its minuscule Jewish community of 2,000. From almost the outset, the identity documents of Jews were stamped with a bold red J.

On October 25, 1942, Jewish men over 50 were arrested by Norwegian police and sent to special camps. At the end of the following month, every Jewish person, regardless of age, was rounded up. The deportees boarded a ship bound for Poland. From there, they were taken to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

Hundreds of Jews escaped through forests to reach Sweden. Berit Reisel says her aunt and uncle spent four days and four nights making the crossing. Some Jews were sent back by Swedish border guards.

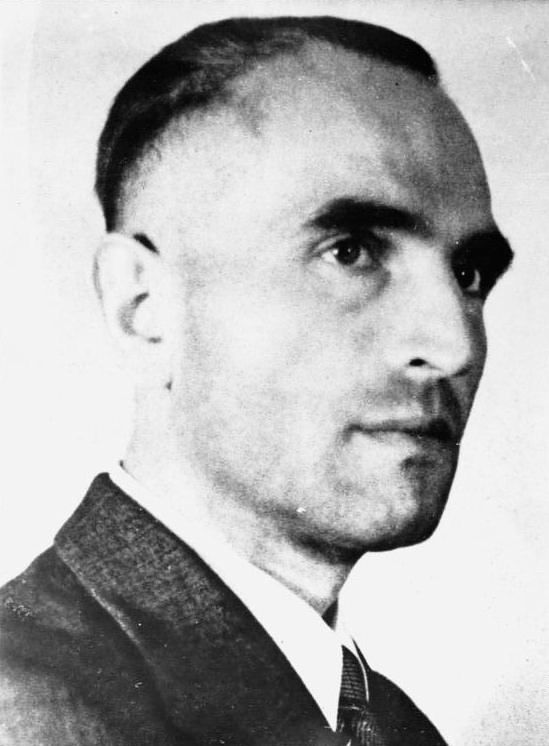

For Danish Jews, the situation grew dire in September of 1943, when SS general Werner Best was given the order to deport Denmark’s Jewish population. He leaked the news to a German diplomat in Copenhagen, and he, in turn, warned the resistance movement, which assisted Jews.

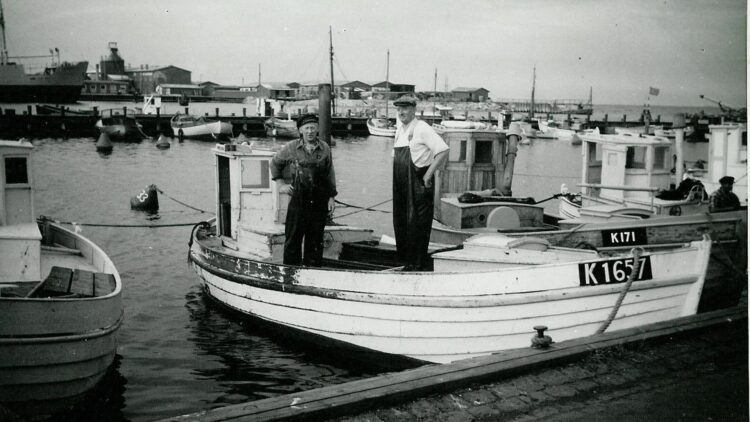

From the northern port of Gillelje, Danish fishermen ferried Jews across a narrow strait to the Swedish town of Hoganas. Dan Edelstein, a Danish Jew, recalls the nerve-wracking tension during the voyage to Sweden, which accepted every Jew reaching its territory.

Jews who returned to their homes after the war were pleased to discover their Christian neighbors had respected their properties.

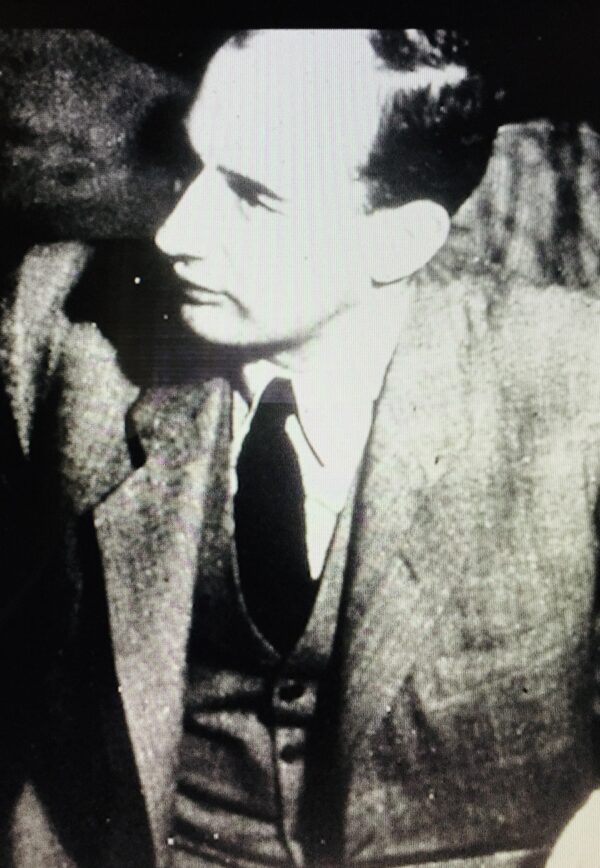

During the war, Sweden offered the Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Hungary a lifeline in the form of Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish national who was posted to Budapest to help Jews. Working in close coordination with the War Refugee Board, a U.S. agency established by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1944, Wallenberg offered Jews special protective passes and a haven in 32 apartment buildings assigned to them.

The pro-German Arrow Cross government sought to demolish these safe houses, but Wallenberg prevailed upon a senior German army officer to squelch their plan.

All told, Wallenberg saved about 100,000 Hungarian Jews. Sadly enough, he disappeared after the war, never to be seen again. By all accounts, he was arrested by the Soviet occupation force, accused of being an American spy.

As the war wound down, the Swedish government launched the White Bus operation to bring 17,000 Scandinavian prisoners of war in Germany to Sweden. Among them were a number of Jews. In the wake of the war, Sweden accepted 10,000 European refugees.

“I was treated very, very well,” recalls Lenke Rothman, one of the Jewish refugees who landed in Sweden. “I felt very safe and protected.”

Warlick tells this story of persecution, rescue and redemption succinctly and competently.