Jews in Eastern Europe once inhabited remote villages known as shtetls. There they lived in splendid isolation for hundreds of years, observing the customs and folkways of their ancestors and speaking Yiddish and the languages of the local region.

The Nazis all but destroyed this vibrant and unique culture in just a few short years. Yet after the Holocaust, its remnants tenuously clung to life in parts of the former Soviet Union, particularly in Ukraine.

Katya Ustinova’s sad and nostalgic documentary, Shtetler, takes a sentimental backward glance at these places and introduces viewers to former residents and a handful of Jews who remained behind. It will be screened at this year’s Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 9-26.

Shtetler begins in Shargorod, a village in central Ukraine that seems far from the beaten track. Volodya, a Ukrainian hat maker who learned the trade from Jews, walks around this woebegone village, pointing to crumbling buildings where his Jewish acquaintances and friends resided before emigrating.

“Kolotinsky lived here, the sausage maker,” he says. “And here stood Hanna Grabert’s house. She sold sparkling water by the glass.” As he looks back, he muses, “All this was a Jewish shtetl. Yeah, this place was full of life once. Everything is gone, and now this place is empty and dismal.” He pauses. “Dear God, where are these people now?”

They have been scattered by the winds of time.

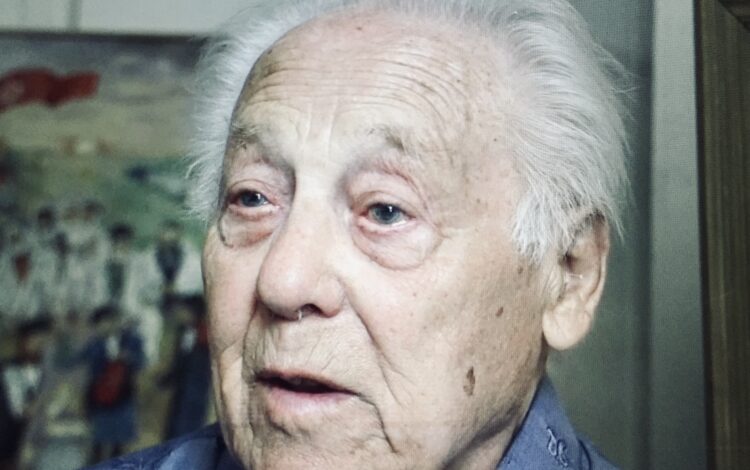

Sofia, in Philadelphia, prepares gefilte fish in her kitchen. Emilia, in New York City, plays a mandolin as she sings Yiddish songs at small concerts. Isaac, a resident of Brighton Beach in New York and a Red Army officer during World War II, paints canvases of shtetl Jews. Vladimir, a Ukrainian convert to Judaism, lives in Immanuel, a settlement in the West Bank.

Emilia, a Holocaust survivor, complains that Ukrainians betrayed Jews during the Nazi occupation. Yet she acknowledges she was saved by a Ukrainian.

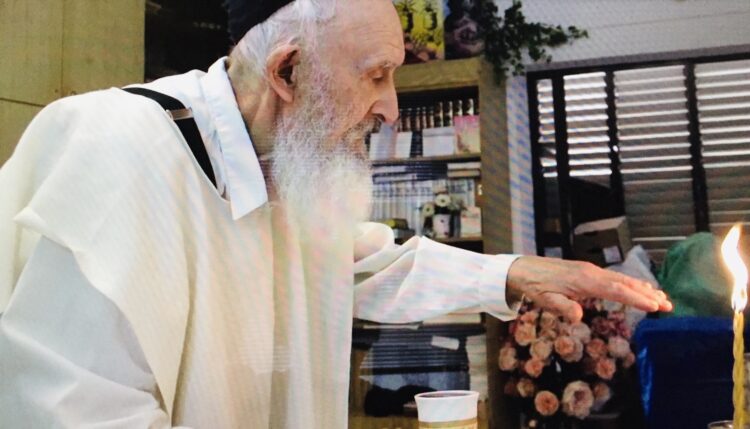

Vladimir’s mother was one of the noble Ukrainians who risked life and limb to help Jews. He grew up with Jews and adopted their ways and habits. In the film, he lights Sabbath candles and prays like a pious Jew.

In the western Ukrainian village of Kolamyia, the camera pans on Shmilo, an observant Jew who was unable to observe Jewish holidays and rituals during the Soviet era. He speaks Yiddish, but has no one to speak to because he’s the only Yiddish speaker here.

Ustinova travels to Chernivtsi, in western Ukraine, and finds Noikh, an Orthodox Jew, at one of the 14 synagogues in the former Soviet Union that always remained open to worshippers. Nowadays, Ukrainian Christians visit the synagogue for free meals and advice from Noikh.

Back in Shargorod, Volodya clears away brush in a Jewish cemetery. He’s not paid for this work. It’s a labor of love.

Slava, a visitor, arrives in Tirgul-Virtiujeni, a forlorn village in Moldova. Inspecting his former home, an abandoned shell of a building, he finds his father’s cap and an oven filled with ash. He chants a heartbreaking song in Yiddish.

“The whole shtetl culture is gone,” he says, lamenting the passing of an era.

His cri de coeur speaks volumes.