No one should be surprised in the least by Iraq’s recent decision to criminalize normalization attempts with Israel, its longtime enemy.

On May 27, Iraq’s parliament passed a law criminalizing contacts between Iraqi citizens, institutions and organizations and the state of Israel, or “the Zionist entity,” as it is derisively known in Iraq.

The new legislation, which supplants a similar law enacted in 1969, imposes the draconian death penalty on violators. The law was proposed by Muqtada al-Sadar, an influential Shi’a cleric and Iraqi nationalist whose political party won the greatest number of seats in last October’s general election.

Iraq has been one of Israel’s most ardent and vociferous enemies both on and off the battlefield. Regardless of whether Iraq has been a monarchy, dictatorship or democracy, the Iraqi elite has been consistently hostile to Israel, and Iraq has never negotiated with Israel.

On the eve of Israel’s declaration of independence in May 1948, the pro-Palestinian Iraqi government made preparations to dispatch soldiers to Palestine. Iraq was then home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the Arab world. Iraq’s active participation in the Arab-Israeli conflict would have disastrous consequences for Iraqi Jews, compelling most to emigrate.

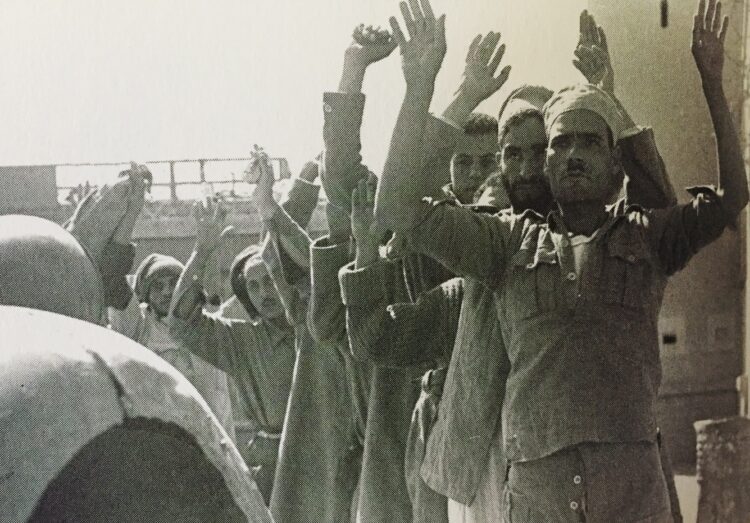

Iraq assembled an expeditionary force of three brigades, consisting of 4,500 troops, to fight in Palestine, according to Benny Morris in 1948, his authoritative account of the first Arab-Israeli war. By his estimation, the Iraqi armed forces were under equipped.

The Iraqis deployed in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan as a junior partner of the Arab Legion, first in the Jordan Valley and then in the hills and foothills of the northern West Bank. A handful of British advisors were attached to the Iraqi army until June 1949.

Iraq’s objectives were two-fold: to destroy the new Jewish state and to seize control of the oil pipeline stretching from Mosul to Haifa.

On May 14, the Iraqis occupied the Naharayim electricity plant in an Israeli enclave just east of the Jordan River. The following day, Iraq pounded Kibbutz Gesher with artillery. This bombardment lasted for a few days. The kibbutzniks fought back ferociously, foiling Iraq’s plan to seize the settlement.

On May 22, Iraq withdrew from the area and redeployed in the West Bank. Once there, Iraq advanced on the coastal plain settlement of Geulim, southeast of Netanya, and seized a pumping station midway between Geulim and Lydda.

By September, the Iraqi force had increased in size to 18,000 soldiers. It was the biggest Arab army fighting Israel.

Iraq’s intervention was a failure. “The (Israeli) nightmare scenario of an Iraqi thrust to the Mediterranean Sea across Israel’s narrow waist (was) averted,” writes Morris.

Iraq’s Arab military partners — Egypt, Trans-Jordan, Syria and Lebanon — signed ceasefire agreements with Israel. Iraq held out, being the only Arab combatant to refuse to abide by an armistice. Since then, Iraq and Israel have been in a continuous state of war.

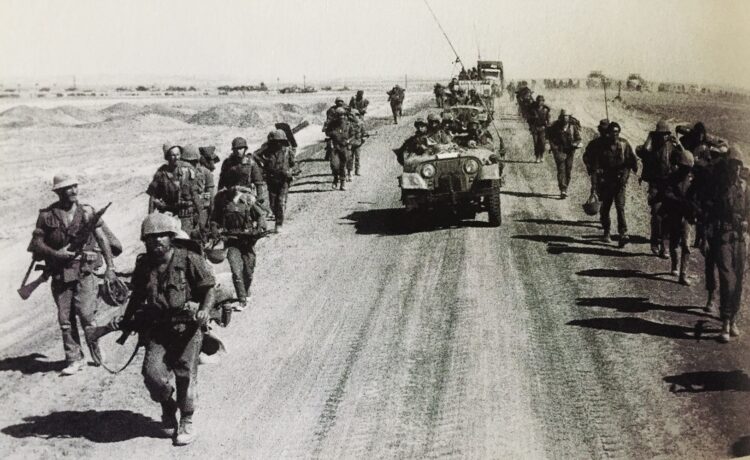

Although not sharing a common border with Israel, Iraq participated in the Six Day War. Iraqi President Abdul Rahman Aref was clear about Iraq’s aim. “Our goal is to wipe Israel off the face of the map,” he declared. “We shall, God willing, meet in Tel Aviv and Haifa.”

Despite Aref’s rhetoric, Iraq’s involvement in the war was limited.

Three Iraqi Hunter aircraft strafed settlements in the Jezreel Valley, including Nahalal, where Israel’s defence minister, Moshe Dayan, was born. An Iraqi Topolov-16 bomber attacked the northern Israeli town of Afula before being shot down. The crash killed 16 Israeli soldiers nearby.

The Israeli Air Force, in turn, attacked the H-3 air base in western Iraq, destroying ten Iraq planes, but also losing 10 of its own aircraft, along with six pilots, to ground fire.

Tellingly enough, Iraq rejected United Nations Resolution 242, which called for a peaceful resolution of Israel’s dispute with the Arabs and Palestinians.

During the Yom Kippur War, Iraq dispatched 30,000 troops, 500 tanks and 700 armored personnel carriers to the Golan Heights to assist its Baathist rival, Syria.

As Abraham Rabinovich writes in The Yom Kippur War, “the Iraqis’ fighting ability did not impress the Israelis.” Yet the Iraqi expeditionary force had an impact on the outcome of the war, he acknowledges. “Unlike the bruised Syrians, the Iraqi forces were fresh and eager to do battle. Confrontation with the Israelis would cool their ardor but their massive presence tied Israel’s forces down” and “neutralized the Israeli threat to Damascus.”

Israel considered Iraq under the rule of Saddam Hussein as a strategic threat.

In 1981, when Iraq was bogged down in what would be a lengthy war with Iran, the Israeli Air Force destroyed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor. Iraq did not respond

A decade later, during the first Gulf War, Iraq fired 39 Scud rockets at Israeli cities, causing relatively minor damage. Saddam hoped that an Israeli armed response would shatter the coalition the United States had assembled to eject Iraq from Kuwait. Under intense U.S. pressure, Israel exercised restraint and did not retaliate.

In 1992, Israel hatched a plan to assassinate Saddam, but it was abruptly cancelled following a training mishap.

During the second Palestinian uprising, Iraq sent funds to Palestinian families in the West Bank and Gaza Strip whose sons and daughters had blown themselves up as suicide bombers.

Through all these years, Israel was the only country that supported the independence of the Kurds in Iraq.

Post-Saddam Iraq has not changed its hostile policy toward Israel. In 2004, Prime Minister Ayad Allawi said Iraq had no intention of reconciling with Israel. And so it has been ever since.

An Iraqi parliamentarian, Mithal al-Alusi, visited Israel in 2004 and 2008, calling for diplomatic relations between Iraq and Israel. But he was a lone voice in the wildernesss, an outlier whose views do not correspond to mainstream opinion in Iraq.