Menachem Begin, Israel’s sixth prime minister, was a man of peace and war. In his six years and three months in office, from 1977 to 1983, he signed a peace treaty with Egypt, for which he won a Nobel Prize, and ordered the invasion of Lebanon, for which he was widely condemned.

Levi Zini’s absorbing documentary, Menachem Begin: Peace And War, portrays him as a politician who was driven by ideological fervor as well as by an abiding sense of realism and pragmatism.

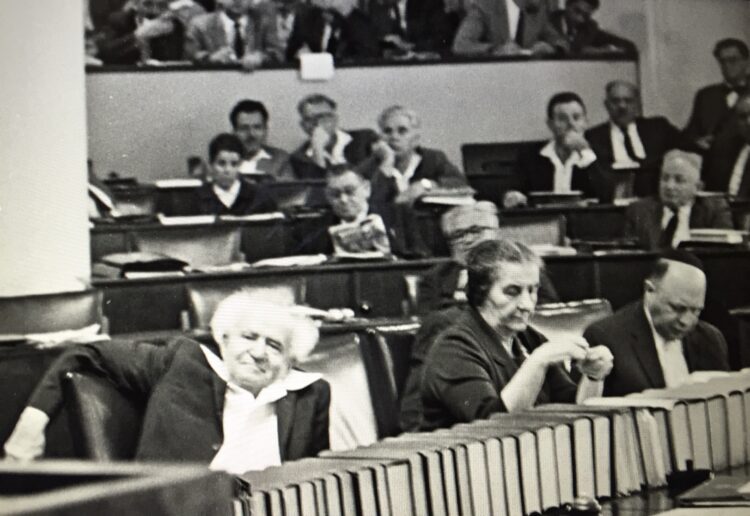

Available for viewing on the ChaiFlicks streaming network from June 15, it is being presented in its new series, The Prime Ministers, which also profiles the careers of David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, Ariel Sharon and Yitzhak Rabin.

Zini’s film, a blend of graphic file footage and interviews with Begin’s associates, begins on the eve of the 1981 election, when Begin, the leader of the right-wing Likud Party, sought to win a second term. He and his Labor Party opponent, Shimon Peres, were running neck-and-neck when Begin pulled a proverbial rabbit out of his hat.

On the eve of the election, Begin, seared by the Holocaust, issued an order to destroy Iraq’s newly-built nuclear reactor, which, he feared, would pose an existential threat to Israel. Israeli fighter jets obliterated the facility in a daring, expertly-executed raid, which reverberated across the Middle East.

Zini leaves the impression that the operation contributed to Begin’s victory at the polls, but in fact it had been planned for months.

Begin, a formal and courtly individual, was first elected in 1977 at the age of 64. Until then, he had been in the opposition for no less than 29 years, during a period when the left-of-center Labor Party completely dominated Israeli politics. Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, regarded Begin as an enemy of democracy and even likened him to Adolf Hitler.

Until this seminal moment, Begin had run in a succession of elections as the leader of the Herut Party, which represented the Revisionist branch of the Zionist movement.

Three days after he defeated Peres, Begin drove to the West Bank to celebrate his triumph with his settler friends and supporters. In a major speech, he promised to build many more settlements.

He was true to his word.

In 1977, only 1,900 Jews lived in the West Bank. Within a decade, the number had jumped to 50,000. By 2019, the West Bank was home to 450,000 Jewish settlers in more than 100 settlements and outposts.

Despite his fervent belief that the West Bank belonged to Israel and could never be relinquished to the Palestinians, Begin attempted to strike a balance between his hardline views and his desire to reach accommodation with Israel’s Arab neighbors. In this respect, his decision to appoint Moshe Dayan as foreign minister was in keeping with this idea.

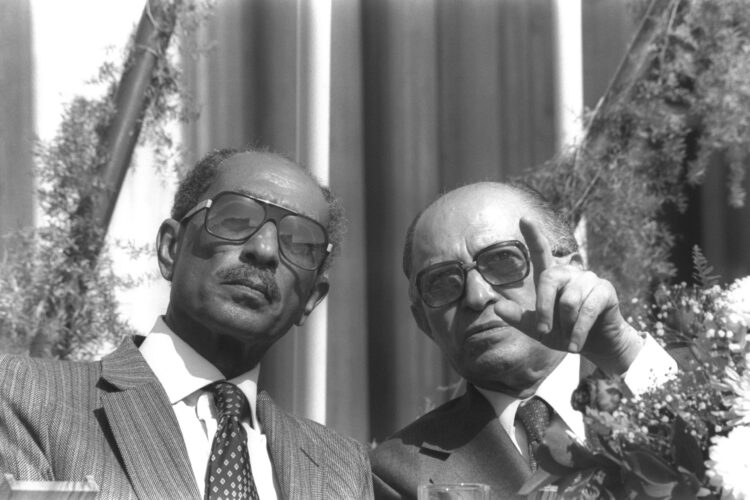

In August 1977, Begin flew to Bucharest on a special mission to inquire whether Romanian President Nicolae Ceausescu, a trusted mediator, could arrange a meeting with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Shortly afterward, Sadat was invited to Bucharest. Ceausescu informed him that Begin would be a reliable partner in peace.

Sadat then announced he was prepared to visit Jerusalem. Begin issued an invitation. In November, Sadat and his encourage arrived in Israel. Only four years had elapsed since the Yom Kippur War. “No more wars, no more bloodshed,” Begin declared in the Knesset.

Sadat expected Begin to embrace his vision of a comprehensive peace accord that included relief for the Palestinians in the form of a two-state solution, but Begin balked. Instead, he offered Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip autonomy, or limited self-rule, a concept that disappointed Sadat.

Nonetheless, at the 1978 Camp David summit hosted by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, Begin and Sadat reached an understanding on the essentials regarding Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula and the elements of normalization.

Begin described Israel’s 1979 peace agreement with Egypt as his third happiest day after Israel’s proclamation of independence in 1948 and the Israeli army’s capture of East Jerusalem during the Six Day War. Peace with Egypt came at a price. Israel had to vacate every inch of the Sinai and demolish settlements there, including Yamit.

In 1981, Israel annexed the Golan Heights. And in the following year, Israel invaded Lebanon. Begin bought Defence Minister Ariel Sharon’s story that Israel would advance no further than 40 kilometres into Lebanon, but this is not the way the war panned out. Israel reached Beirut in a campaign that entangled Syria in the fighting. Begin insists he was not deceived by Sharon.

Much to Begin’s profound disappointment, Israel’s Maronite Christian ally in Lebanon, Bashir Gemayel, told him he could not sign a peace treaty with Israel as long as he remained prime minister.

By this point, the Israeli public had soured on the war. It became all the more unpopular after Lebanese Christian militiamen allied with Israel slaughtered some 800 Palestinians civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps near Beirut.

A year later, Begin resigned. “I cannot go on any longer,” he confessed.

Crushed by the subsequent death of his wife, Aliza, Begin retreated into himself. He died in 1992.

Begin was a politician who kept faith with his philosophy. He was determined to retain the West Bank, the ancestral land of the Jewish people, yet he was flexible enough to cede the Sinai to Egypt and thereby change the regional balance of power.

Zini, in this film, clearly recognizes the range of Begin’s strengths and weaknesses.