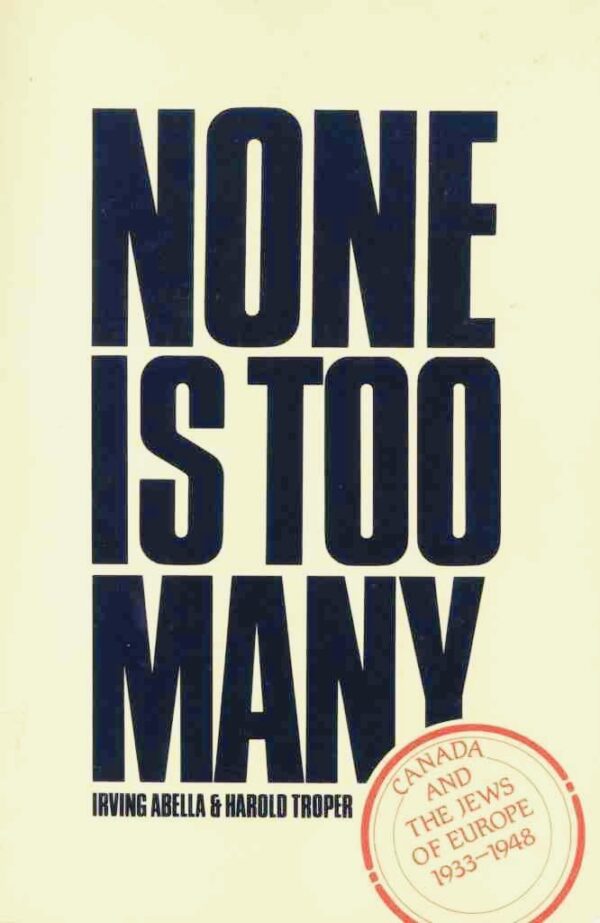

Irving Abella left an indelible mark as a scholar, particularly after the publication of his landmark book, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948, in 1982. From that point onward, he and his co-author, Harold Troper, were recognized as two of the most preeminent Canadian historians of their generation.

A stinging critique and expose of Canada’s restrictive immigration policy before and during the Holocaust, it struck a chord with readers. In fluid prose, they demonstrated beyond a doubt that Canada’s selection of new immigrants was guided by a preference for northern and central European Christians and was impregnated with antisemitism.

At a fraught moment when fascist regimes in countries like Germany, Italy, France, Hungary, Slovakia and Romania were persecuting and murdering Jews on an industrial scale, the Canadian government drastically limited the number of Jewish refugees allowed into Canada.

Abella, a York University professor who launched his academic career as a labor movement historian, went on to write several more books, but they did not attain the acclaim or popularity of his masterpiece, None Is Too Many, which was doubtless the most important book in Canadian historiography in decades.

Abella, who held the J. Richard Shiff Chair for the Study of Canadian Jewry, died in Toronto on July 2 after a long illness. He was 82.

I met him once. As a journalist, I interviewed him following the release of Coat of Many Colours: Two Centuries of Jewish Life in Canada. I found him to be quiet and self-effacing, the polar opposite of a publicity hound. As they say in Yiddish, he was not a schwitzer.

By then, to be sure, he was something of an elder statesman in academia.

During the 1970s, at Glendon College, he created the first course in Canadian Jewish studies at the university level. Today, close to a dozen universities in Canada offer such courses.

And along with Troper and colleagues like Gerald Tulchinsky and Richard Menkis, he was instrumental in establishing a nation-wide archives geared to the interests of historians specializing in this field.

David Koffman, the current occupant of the J. Richard Shiff Chair for the Study of Canadian Jewry, was one of Abella’s colleagues. On Abella’s 80th birthday, Koffman wrote, “Irving Abella’s importance as a historian stands in its wide public reach, in its impeccable and incisive scholarship, and in the fact of his fellow historians’ steady citations of his work from a wide range of Canadian and modern Jewish historical subject areas. He produced a prodigious body of scholarly writings in books, journal articles, print essays in public intellectual magazines, encyclopedias, newspaper editorials, interviews, and innumerable public and academic lectures around the world.”

From a reputational point of view, Abella is best known for None Is Too Many, which took four years to research and write.

Less than a year before it was published by Lester & Orpen Dennys, I got a glimpse of it when I interviewed Troper, a professor of history at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. As he discussed it, I realized it was going to be a blockbuster in terms of its scholarly importance and its impact on the public.

In their preface, Abella and Troper placed their topic in historical perspective. In early 1945, an anonymous senior Canadian government official was asked by a reporter how many Jews would be accepted into Canada after World War II. “None is too many,” he replied blandly, echoing the opinion of a substantial proportion of Canadians.

“The reply and the policy it reflected stand in sharp contrast to the current image of Canada as a country of immigrants, a country with a long and enviable history of welcoming the world’s refugees and dissidents,” the two authors wrote in the preface. “Why, then, during the thirties and forties could Canada find no room for the tormented Jews of Europe?”

Canada’s record in this respect was abysmal.

During the 15-year period surveyed by Abella and Troper, the United States, Britain, Argentina and Brazil respectively admitted 200,000, 70,000, 50,000 and 27,000 Jewish refugees. Bolivia and Chile each let in 14,000 Jews. Palestine, a British colony, permitted the entry of 125,000 Jewish refugees.

Canada found room for only about 5,000 Jewish immigrants, thereby compiling “the worst record for providing sanctuary to European Jewry,” they state starkly.

“Canada’s door was shut most tightly to Jews,” they add in a stinging indictment.

As they point out, Canadian immigration policy had always been ethnically selective, with preference given to northern and then central Christian Europeans. At the bottom of the rung were Jews, Asians and Africans.

From 1935 onward, the powerful civil servant entrusted with the task of ensuring that restrictions on immigration were upheld was Frederick Charles Blair, the director of the Immigration Branch of the Department of Mines and Resources. Described by Abella and Troper as an antisemite, Blair feared that Canada would be “flooded with Jewish people.”

As much as they blame Blair for Canada’s racist policy, they single out the then prime minister, Mackenzie King, for keeping Jews out of Canada.

Canadian policy gradually changed in the wake of the war, transformed, in part, by C.D. Howe, the influential minister of reconstruction and supply, who believed that increased immigration would be helpful to the economy during the postwar period.

Displaced European Jews who had survived the Holocaust, like my parents David and Genia, were permitted to settle in Canada.

By the time Abella and Troper got around to researching and writing None Is Too Many, which is still in print and available for sale on Amazon, Canada had liberalized its position toward immigration and refugees.

Since then, Vietnamese, Syrians and, now, Ukrainians have been welcomed to Canada as immigrants.

The overt racism that defined Canadian immigration policy until about two generations ago, the one documented with passion and precision by Abella and Troper, is a thing of the past.