Before the creation of the state of Israel, American Jews immigrated to Palestine — a League of Nations mandate administered by Britain from 1922 to 1948 — in extremely small numbers But as Joseph B. Glass suggests in his deeply-researched and revealing book, From New Zion To Old Zion: American Jewish Immigration and Settlement In Palestine 1917-1939 (Wayne State University Press), their contributions to the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, were quite significant.

American Zionists worked the land, founded settlements and poured funds into municipal projects. A few achieved national prominence. Ukraine-born Golda Meir went into politics and played a major role in building the country. The Reform rabbi Judah Magnes was the president of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

According to Glass, American aliyah began as a trickle in the mid-19th century, when Palestine was an Ottoman Turkish colony. These Americans, mostly of East European origin, gravitated to the Holy Land to study Torah and to be buried in its soil after their deaths. By 1913, eight American citizens lived in Haifa and another ten resided in Zichron Yaakov.

From 1920 to 1939, an average of 400 American Jews settled in Palestine, comprising about 2.5 percent of the total Jewish immigration. Approximately 9,000 Americans immigrated there during this period. Many were first-generation Americans.

American Orthodox Jews originally from Eastern Europe were in the vanguard of aliyah. They were usually older and generally depended on financial support from abroad. In the main, they chose to live in Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, Hebron and Jaffa.

Apart from pious Jews, Palestine attracted single young men and women from movements such as Hashomer Hatzair. Known as halutzim, they were drawn to collective settlements such as Degania, Ginossar and Givat Brenner.

What Glass describes as “middle-class agriculturalists” dreamed of buying farms. This group, consisting mainly of families, founded the settlements of Ein Hashofet in 1937, Kfar Menachem in 1939 and Kfar Blum in 1943.

Urban professionals, ranging from doctors and lawyers to engineers and social workers, arrived in Palestine as well. Most had been raised in America from an early age.

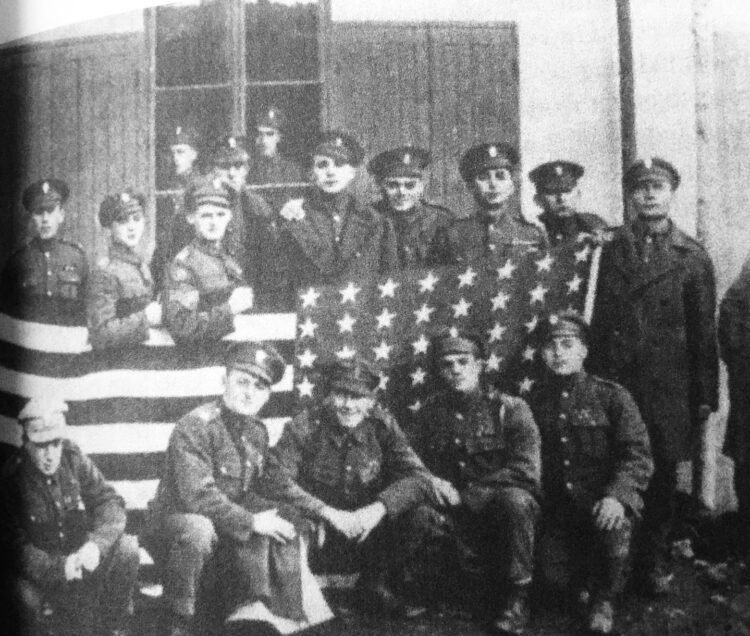

Still other Americans residing in Palestine had served in the Jewish Legion during World War I, having hoped to liberate Palestine from Turkish rule.

Jewish students studied in Palestine. From 1926 to 1938, 69 Americans attended the Hebrew University. Among them were graduates of rabbinical schools.

Palestine offered certain career opportunities and economic advantages, especially after the Great Depression, writes Glass.

Nonetheless, the vast majority of Jews in the United States had no interest in settling in Palestine. Zionist leaders such as Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion were under no illusions on this score. They believed that American Jews could best be of help to the Zionist cause by donating money to its coffers.

The Reform movement was initially anti-Zionist, as its 1885 Pittsburgh Platform stated: “We consider ourselves no longer a nation but a religious community.” With the passage of time, Reform Jews endorsed Zionism.

Jews on the left, including socialists, communists and trade unionists, opposed Zionism. The Workmen’s circle, which was controlled by Bundists, regarded Zionism as a bourgeois religious movement that ignored basic social issues and sought to impose a Jewish national home on a hostile indigenous Arab population.

Abraham Cahan, the editor of the Jewish Daily Forward, the preeminent Yiddish newspaper in the United States, was lukewarm to Zionism. But after visiting Palestine in 1925 he had a change of heart and regularly published articles about Zionism and conditions in Palestine.

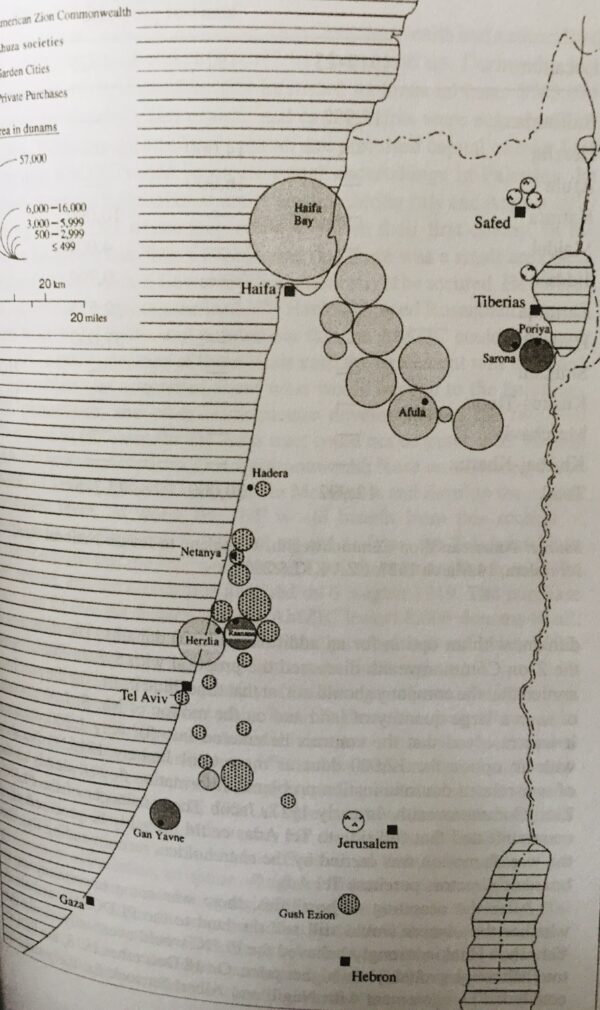

Americans pooled their resources to establish new settlements. “An American group would employ Jewish workers to prepare the land, plant fruit-bearing trees, and maintain them,” says Glass. “After six or seven years, when the plantations bore sufficient fruit to provide an income for its owners, the land would be parcelled and transferred to the individual owners waiting to immigrate, settle their land and assume its maintenance.”

Simon Goldman of St. Louis organized the first such group in 1912 in Poria, a village near the Sea of Galilee which is now a suburb of Tiberias.

The town of Raanana, close to Tel Aviv, was founded in 1922 by Jews from New York state. The first settlers planted vegetables, barley and tobacco, but eventually they specialized in orange cultivation. German Jews settled in Raanana in the 1930s, but after 1948 it attracted American and Canadian Jews. Naftali Bennett, Israel’s former prime minister, lives there today.

American investors established Herzlia in 1921 after purchasing land from the Arab villages of Jelil and El Haram. The citrus industry supported Herzlia economically, but today it’s a wealthy suburb of Tel Aviv.

American Jewish settlement was not limited to privately-owned lands, says Glass. The Jewish National Fund created a program for the settlement of middle-class Americans.

During the 1920s, Americans provided financial assistance to improve Tel Aviv’s infrastructure. One such person, Bernard Rosenblatt, was a member of the Palestine Zionist Executive. Americans also invested in the construction of residential homes and commercial buildings in Tel Aviv.

In closing, Glass says that Americans were instrumental in the development of Palestine. “American Jewish activity resulted in the employment of Jewish workers, the development of settlements dependent upon American Jewish agricultural investment, improvement in the quality of life in Palestine, the attraction of capital to Palestine, and the introduction of new ideas and social norms.”

Relatively few Americans settled in Palestine, but they made a substantial difference.