Cecil B. DeMille was a major force in the Hollywood movie industry for decades. From 1913 until the late 1950s, he directed more than 70 silent movies and talkies and worked with the leading actors of the day.

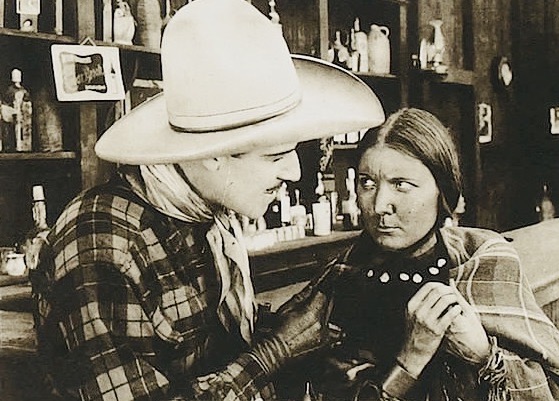

More than 60 years after his death, he is probably best remembered for, among other pictures, The Squaw Man, the first American feature film, and The Ten Commandments, a remake of his 1923 silent movie.

“DeMille loved to mix highly theatrical hokum with often pious sentiments and technical finesse,” writes Robert Birchard in Cecil B. DeMille’s Hollywood, published by University Press of Kentucky. Birchard a seasoned film historian, argues that his “flair for screen storytelling and his patent sincerity” made his movies “enduringly entertaining.”

Birchard’s authoritative book is not a conventional exercise in biography. He appraises DeMille strictly through the prism of his movies, many of which were box-office successes. It’s a fairly original approach, but it leaves something to be desired inasmuch as it omits the nuances of DeMille’s personality, career and work methods, and Hollywood’s development as an American cultural hub.

In this fashion, he glosses over DeMille’s formative years. DeMille, born in Ashfield, Massachusetts in 1881, was the second son of Henry Churchill DeMille, a lay minister in the Episcopal church and a playwright. His mother, Matilda Beatrice Samuel, was a Jewish convert to Christianity.

DeMille was clearly a Christian, but in halachic terms, he was Jewish. Birchard refers only once to his Jewish roots. In a passage in which he discloses that DeMille “abhorred ethnic or racial bigotry,” he writes, “His mother was Jewish.”

Before his entry into the movie industry, DeMille had achieved only modest success as an actor, producer, play broker and writer. Indeed, he was buried under a mountain of debt and faced a bleak future at the age of 32. But after meeting the up-and-coming filmmaker Jesse L. Lasky, whose brother-in-law was Samuel Goldwyn, DeMille’s fortunes improved markedly.

When Lasky formed the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, he hired DeMille as the director general and Goldwyn as general manager. By then, Los Angeles was already a production centre of note.

One of their first movies, The Squaw Man, showed a net profit of $244,700, an extraordinary figure in the silent era. In 1931, DeMille directed a sound version starring Warner Baxter and Lupe Velez.

In one of his next films, The Virginian, DeMille demonstrated a more mature grasp of the medium, moving the camera closer to the actors and showing a greater reliance on personality and subtlety of performance.

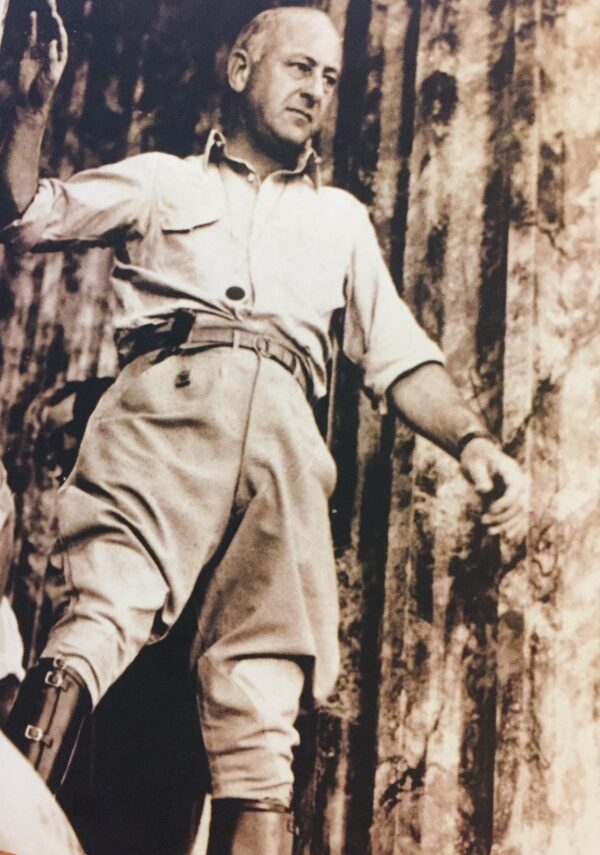

DeMille, a domineering figure during filming, expected actors to bring their skill and insights to the set. “When asked by actors how to play a scene, DeMille would say that he wasn’t running an acting school, that they were hired because he felt they could do the job,” says Birchard.

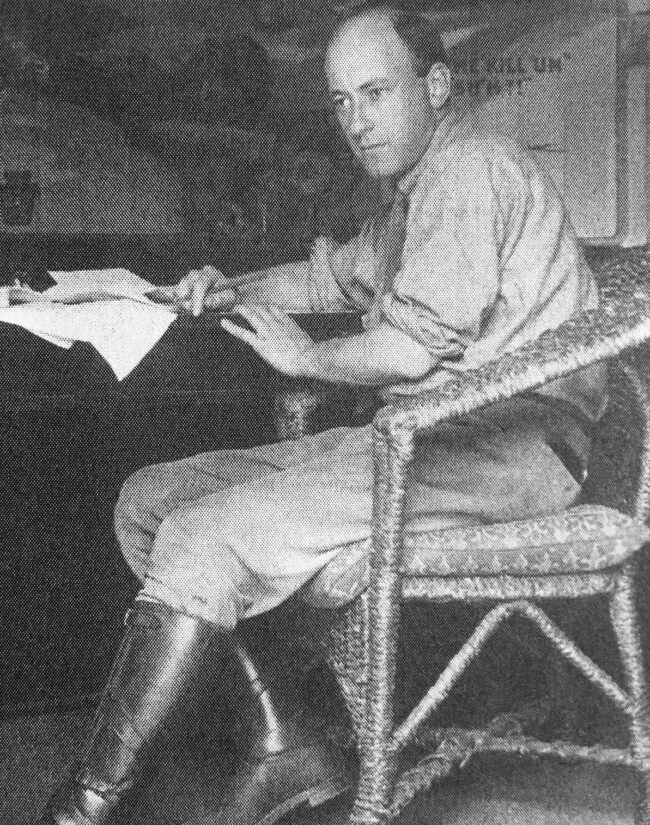

On sets, he wore the same “uniform” — jodhpurs and puttees, open-necked shirt, and slouch hat, often with a holster and a revolver.” In Birchard’s opinion, “these costume pieces lent an air of authority to DeMille’s presence around the studio.”

DeMille was a very busy man during this period, writing scripts for 18 of Lasky’s 30 films in 1915 and directing 13 of them.

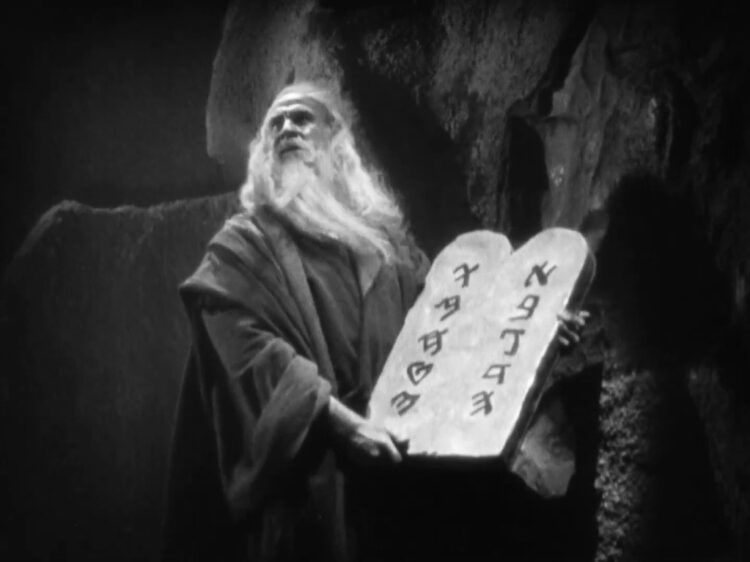

In 1923, he directed The Ten Commandments, the most expensive picture up to that time. The sets were spectacular, requiring the services of 500 carpenters, 400 painters and 380 decorators. As many as 2,500 extras were used. In 1954, he spent two months in the Sinai Peninsula directing a new version of it. The critics were ambivalent, but Birchard describes it as “a very moving, even spiritual experience.”

DeMille’s transition into sound movies appears to have been seamless, judging by his 1930 musical, Madam Satan.

Hot on the heels of two biblical blockbusters, The Sign of the Cross and Cleopatra, DeMille directed his most ambitious film to date, The Crusades, which telescoped seven Crusader campaigns in Palestine from 1096 until 1291. For a while, censors in Palestine and Egypt rejected the film.

The Plainsman, a Western, was released in 1937 and was a tremendous hit. It inspired a new cycle of Westerns from Wells Fargo to Stagecoach.

His first film to be shot entirely in color, North West Mounted Police, was premiered in Regina in 1940. “It (established) the photographic style for all his future productions,” writes Birchard. “Brightly lit, with rich, saturated hues, the film has a story-book quality that is vivid and pleasing to the eye, but also rather stylized and theatrical.”

The Greatest Show On Earth, starring Charlton Heston and Betty Hutton, was released in 1952. It was a “phenomenal hit” and earned DeMille an Academy Award for best picture.

Unlike most most Hollywood veterans, DeMille was politically conservative. Nonetheless, one of his movies, The Volga Boatman, had an open-minded view of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. And interestingly enough, DeMille gave Edward G. Robinson, a known leftist who had been blackballed by the studios, a role in The Ten Commandments. Robinson was grateful for DeMille’s tolerance of political diversity, calling him a person of “decency and justice” who was instrumental in reviving his career.

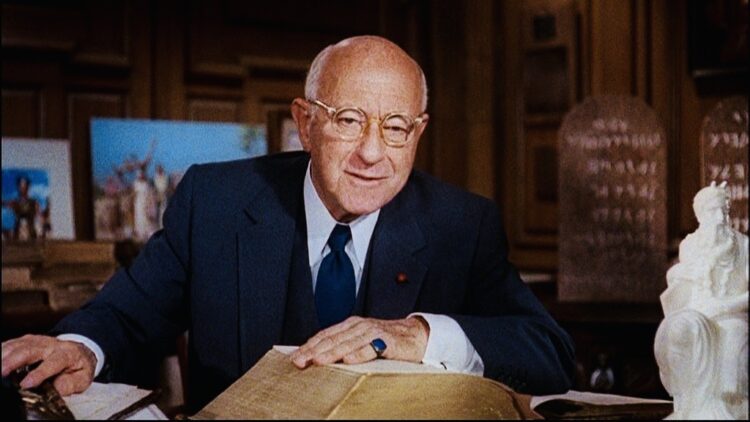

DeMille died in his home on January 31, 1959, his place in the pantheon of Hollywood greats assured. Birchard, in his informative book, gives him the credit he so richly deserves.