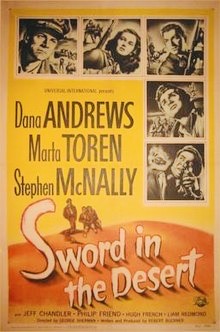

The first ever Hollywood movie about Israel’s struggle for statehood, Sword in the Desert, was released in the United States in 1949, a year after Israel achieved sovereignty and independence. Directed by George Sherman, and based on a short story by Robert Buckner, it appeared eleven years before Otto Preminger’s Exodus.

Filmed in California, and starring Dana Andrews as a hardboiled American ship captain who brings a group of Holocaust survivors to Palestine on the eve of the 1947 United Nations partition plan, this one hour-and-40-minute black-and-white pro-Zionist feature film stirred unease in certain circles.

Newspapers in Britain, defending Britain’s League of Nations mandate in Palestine, denounced it as anti-British.

In his review in The New York Times on August 25, 1949, chief movie critic Bosley Crowther delivered a mixed verdict. While describing it as “a generally exciting action thriller,” he doubted whether it was “socially constructive.” As he explained, “The consequences of such heavy loading of sympathy on the Jewish side tends to create dramatic distortion, which dissipates credibility.” He added that the picture might “spread a damaging impression of a tragic chapter in recent history.”

Crowther’s qualms were hardly surprising, given the generally anti-Zionist outlook of the Sulzburgers, an assimilated Jewish family which owned the Times.

In fact, Sword in the Desert, which was screened on the Turner Movie Channel on July 13, is not overtly anti-British, but rather consistently sympathetic to the Jewish cause.

There is a fleeting reference to the “British army of occupation.” One of the major characters, a young Zionist activist named Sabra (the Swedish actress Marta Toren), blurts out that Britain has “no right” to occupy the ancestral Jewish homeland. And in a contemptuous remark, a British army officer calls Palestine a “godforsaken land.”

The Brits, though, are not portrayed as vicious monsters, but as colonialists who are trying to cling to a far-off imperial possession.

Sword in the Desert begins at night off the coast of the Gaza Strip as Mike Dillon (Andrews), the captain of the Eastern Star, impatiently waits to offload a boatful of illegal Jewish refugees, whom he condescendingly labels as a “mob.”

Dillon, having agreed to transport them to Palestine in contravention of British immigration regulations, is a “blockade runner.” But he has no sympathy for the ragged Jewish passengers clamoring to leave his ship, nor is he morally invested in Zionism.

“I’m an American, this isn’t my fight,” he says, tartly reflecting the anti-Zionist position of the U.S. State Department and the American security apparatus.

All that concerns him is the $8,000 fee he expects to pocket for having transported the bedraggled refugees to Palestine.

David Vogel (Stephen McNally), a Zionist official aboard the vessel in charge of the refugees, offers a far different perspective. Having survived Nazi ghettos and extermination camps, they regard Palestine as their “last hope” for renewal, he says.

Landing on the beach, the refugees display a sense of relief and astonishment. An exuberant Jewish soldier who greets his long-lost father waxes poetic, saying it took him 2,000 years to reach the shores of Palestine. Jerry McCarthy (Liam Redmond), an Irish volunteer with a thick brogue, greets the refugees like brothers and sisters.

With a British patrol boat approaching the beach, Dillon complains. “This is a swell mess you got me into,” he says bitterly.

As British troops disembark, trucks packed with refugees head into the desert, dodging a hail of bullets. Watching the passing vehicles, a Palestinian Arab spits on the ground. This is virtually the only instance when Arabs are seen on the screen. For all practical purposes, they are invisible in this film.

The scene shifts to a recording studio, where Sabra, a vivacious young woman with a distinct Swedish accent, broadcasts the latest news about the “Jewish army of resistance” on the Voice of Israel. Another announcer reminds listeners that British rule is coming to an end.

The refugees reach a kibbutz and are greeted warmly by its inhabitants. Dillon is indifferent to his surroundings. Consumed by the desire to reclaim his ship, he fears that it will be seized by the British and that he will lose his captain’s licence. Vogel promises to help him if he pledges to deliver yet more Jewish refugees to Palestine.

Kurta (Jeff Chandler), a Jewish functionary, expresses apprehension that the Arabs are growing stronger by the day and that they may wipe out the Jewish community.

The British arrive at the kibbutz and proceed to arrest Kurta and Sabra. Suspecting she’s the elusive Voice of Israel announcer, they force her to read one of her recent bulletins. “You have occupied our country and deprived us of our home and freedom,” she says. “So we must fight you. There is no other solution.”

Contemplating the rising tide of violence in Palestine, a thoughtful British officer observes, “This is not a Jewish or an Arab problem, but a problem for all of mankind.”

Dillon, still enmeshed in the standoff between the Zionists and the British, agrees to identify Kurta if he can regain his ship. At the last moment, he has a change of heart, endearing himself to Zionist officials. And in one of the final scenes, a Jewish force attacks a British base, freeing prisoners.

By any yardstick, Sword in the Desert is a competently-crafted, well-acted film with a blazing message. It does not feel campy in the least, but its rank dismissal of the Palestinian case would not pass muster today. It’s a cinematic time capsule that sheds light on a bygone era which laid the foundation for the creation of the state of Israel.