On September 20, 1940, Adam Czerniakow, the chairman of the Nazi-appointed Jewish Council (Judenrat) in the Warsaw ghetto, was summoned to the office of Ludwig Leist, the governor of German-occupied Warsaw. Leist ordered him to establish a Jewish police force. Known as the Jewish Order Service, it was modelled after the Jewish Council’s Security Guard, which had been formed at the end of 1939 to deliver forced labor workers to the Germans.

The Jewish Order Service, which performed a wide array of tasks, had a relatively brief life span, having outlived its usefulness following the 1943 ghetto uprising.

Katarzyna Person, a historian at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, has written a sober and comprehensive account of this collaborationist organization. Warsaw Ghetto Police: The Jewish Order Service During the Nazi Occupation, ably translated into English by Zygmunt Nowak-Solinski, is published by Cornell University Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The Jewish Order Service, the Jewish equivalent of the Polish Blue Police, was not an independent entity, reporting to the German Order Police, the Blue Police and the Jewish Council. It had no trouble signing up recruits, as the Jewish diarist Emanuel Ringelblum noted. “Everyone is pulling strings to get these sought-after positions,” he wrote.

Lawyers, engineers, the sons of well-connected businessmen and even yeshiva graduates joined the Jewish police force. Conditions for admission were strict. Candidates had to be in good health and could not be younger than 21 or older than 40. They had to be at least 5 feet 7 inches tall and weigh a minimum of 132 pounds. They must have completed their military service and could not have a criminal record. They were required to provide two references.

The Jewish newspaper Gazeta Zydowska reported that thousands of applications were submitted. By mid-November 1940, 1,635 candidates had been selected. Within a few months, the number of police surpassed 2,000. Several hundred more joined the force in 1941.

By one estimate, the largest professional group in it were office workers (28 percent), followed by merchants and industrialists, representatives of the free professions, technicians, craftsmen and students.

The benefits of membership outweighed the disadvantage of being scorned as a collaborator. Among the privileges police enjoyed were requisition-free apartments, free health care, exemption from deportations, and passes enabling them to temporarily leave the ghetto.

Their tasks varied, running the gamut from controlling the prices of food to regulating pedestrian and vehicular traffic. They were also expected to keep pavements, roads and courtyards clean, combat smuggling, prevent anyone from sneaking through gaps in the walls and fences, and remove corpses. As well, they secured ghetto walls and rounded up inhabitants for forced labor assignments.

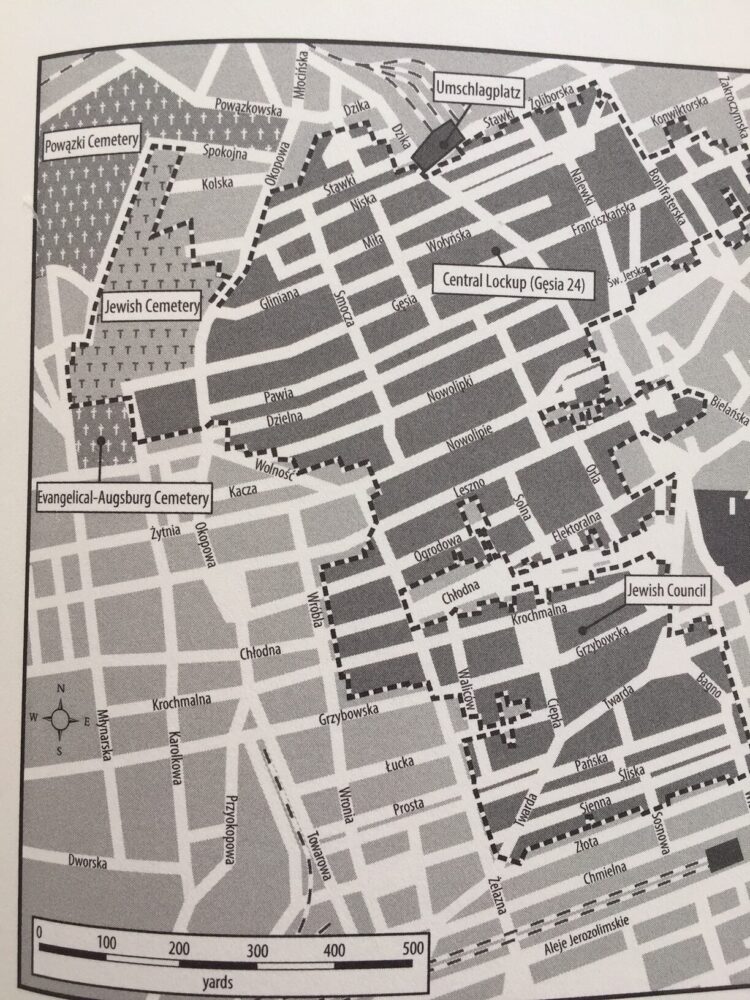

With the mass deportation of Jews to the Treblinka extermination camp in the summer of 1942, policemen were ordered to bring 6,000 people to the Umschlagplatz assembly point each day. In his diary, Abraham Lewin described their “savagery” and “murderous brutality” in performing this gruesome role.

To the inhabitants of the ghetto, the police were nothing less than traitors doing the bidding of the Germans. They were also viewed as corrupt, extorting bribes for certain services and taking part in smuggling operations to and from the ghetto.

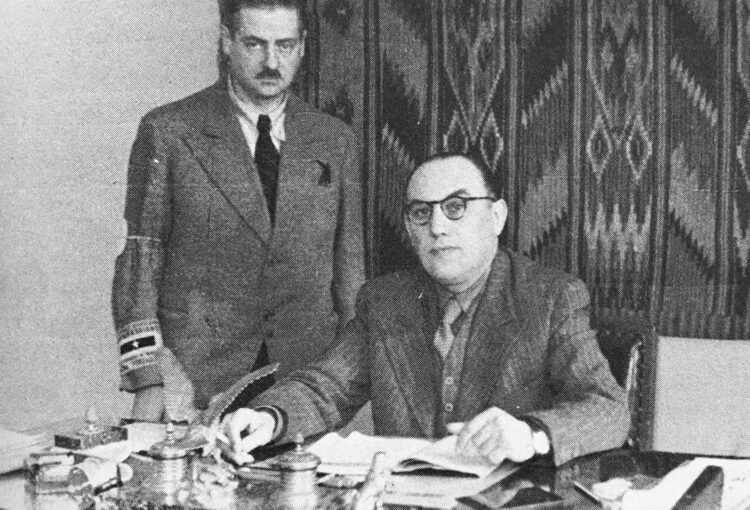

Jozef Szerynski, a convert to Christianity, was the commander of the Jewish Order Service until May 1942. Described by Person as as “a man gifted with great ambition and talent,” he joined the Police State Police in 1920. Promoted to the position of deputy inspector in 1930, he served in Lublin from 1935 to 1939.

One of his deputies, Marian Handel, was an intermediary between the police force and the German administration.

“Szerynski entrusted the remaining high-level positions in the Jewish Order Service to friends and colleagues from before the war, mainly lawyers coming from highly polanized or assimilated social circles,” writes Person. “Despite his prewar position, Szerynski remained alienated within the Jewish community.”

He was arrested by the Germans in the spring of 1942, charged with a relatively minor misdemeanor. Szerynski committed suicide less than three months before the ghetto uprising. His death was “widely read as a sign of divine justice,” says Person.

He was succeeded by Jakub Lejkin, a functionary in the force whose reputation for efficiency preceded him. Lejkin played a central role in the roundup of 265,000 Jews in July 1942. Czerniakow, having been informed that Jews would be “resettled,” killed himself.

“The participation of the Jewish Order Service in the deportations provoked horror,” says Person.

Jewish policeman demanded cash, jewelry and other valuables for exemptions from the massive roundups. They extorted sexual favors from women for the same service.

Lejkin was assassinated on October 29, 1942 by a combatant from the Jewish Fighting Organization. Shortly afterward, Jewish assassins killed Israel First, the head of the Judenrat’s Economic Department and a Gestapo agent, and Jerzy Furstenberg, Handel’s adjutant.

In the wake of the mass deportations, with 70,000 Jews still eeking out a bare-bones existence in the ghetto, the Jewish Order Service was tasked with the mission of patrolling it and escorting workers to workplaces.

Ultimately, Jewish policemen shared the fate of the remaining Jews. Some were executed, often near the notorious Pawiak prison, or deported. An undetermined number managed to escape to the Aryan side of the city.

Jewish policemen in postwar Poland were arrested and placed on trial. Some tried to convince courts they had been mere cogs obeying orders. Some were cleared of charges. Still others emigrated under assumed names. Person cites the name of one such individual — Szapsel Rothole, who went to Montreal and earned a living as a furrier.

Poland’s Communist regime generally presented the Jewish Order Service as an oppressive institution imposed on the ghetto by the Nazis and controlled by a Jewish bourgeoise loyal to the Judenrat and the Nazi occupation authorities.

It is certainly clear, as Person suggests, that the Jewish Order Service worked under appallingly horrible and impossible conditions and betrayed the people it was supposed to protect.