Duki Dror’s whimsical documentary, There Are No Lions In Tel Aviv, charts the formation of the first zoo in pre-state Israel and fleshes out the personality of its eccentric founder, Rabbi Mordecai Schornstein. This one-hour film is now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform, which specializes in Jewish and Israeli topics.

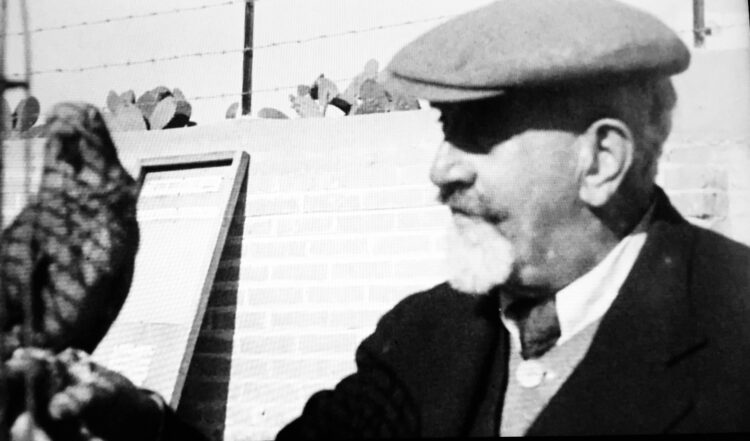

The zoo was officially opened in Tel Aviv on December 17, 1938, three years after the rabbi’s arrival in British Mandate Palestine. It was located next to what would would be Tel Aviv’s city hall. Back in the 1930s, this neighborhood in the northern part of the city was covered in citrus orchards.

Dror’s film is a melange of file footage and interviews with the rabbi’s granddaughter and residents of Tel Aviv who fondly remember the zoo in its infancy.

“It was a magical place,” an elderly man recalls, citing its immense variety of animals, ranging from bears and monkeys to leopards and crocodiles. “Going to the zoo was a pleasure,” says another man.

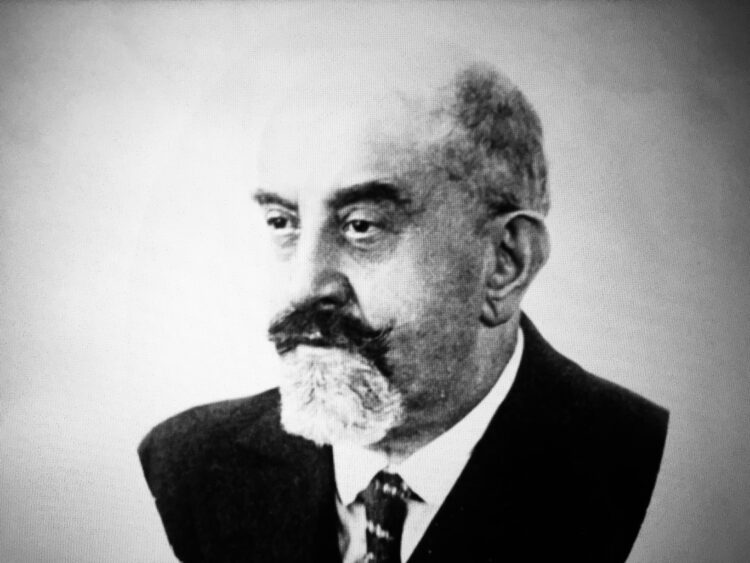

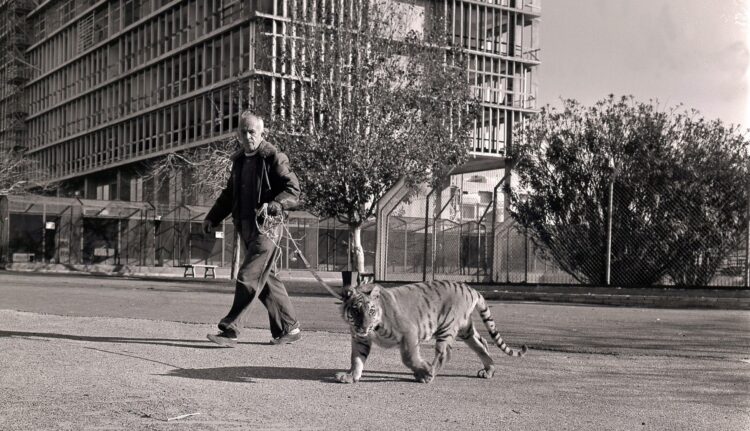

Schornstein, the former chief rabbi of Copenhagen, left Denmark after his retirement and the death of his wife. Arriving in Tel Aviv with two bird cages, he opened Tel Aviv’s first pet shop on Sheinkin Street. Shortly afterward, he founded a makeshift zoo on his property on Hayarkon Street. Eventually, he acquired an impressive collection of creatures, including two lions.

“When grandfather was with animals, he was intoxicated,” says his granddaughter. “He loved them with all his heart and soul.”

Not surprisingly, Schornstein’s neighbors complained about the unpleasant odors, forcing him to dismantle the zoo. Thanks to an association that shared his desire to build a zoo, he acquired land in north Tel Aviv to start the city’s first official zoo. At Schornstein’s request, he was its first general manager.

Presented as a Zionist enterprise, it was popular with adults and children alike.

One of its employees, Johnny Zusia, was a German Christian who had lived on a kibbutz and hated the Nazi regime in Germany.

Schornstein’s granddaughter claims he was not always paid a salary and sometimes went hungry. In desperation, he took a “loan” of three shekels from the zoo’s till to buy himself food. The theft was reported, resulting in his arrest. A sympathetic judge dealt leniently with him, but Schornstein was dismissed from his position.

By that point, he and the members of the zoo association were barely on speaking terms. The film acknowledges that Schornstein was a difficult man with a short temper.

In the meantime, following the outbreak of World War II, Johnny Zusia was interned as an enemy alien. The mayor of Tel Aviv, Israel Rokach, pleaded with the authorities for his release.

After his dismissal, Schornstein moved to Jerusalem, where he opened a bird sanctuary. He died in 1949.

By the early 1960s, Tel Aviv had expanded and the zoo, located on a valuable plot of land, was definitely in the wrong place. The municipal building had been constructed and luxury apartments were rising nearby. With residents carping about the noise and the smells, the zoo was closed in 1980 and transferred to a far more spacious area in the suburb of Ramat Gan.

As Dror suggests, speculation abounded that its transfer was due to corruption and shady deals, but he does not explore this facet any further.

This charming film ends on a philosophic note, implicitly asking viewers to ponder the question whether zoos in principle are good for animals. Schornstein, I’m certain, would have responded affirmatively.