It was a brief political partnership, yet it was remarkably eventful and predictably disappointing.

Naftali Bennett, a rightist, and Yair Lapid, a centrist, formed an expedient alliance after the inconclusive 2021 general election in Israel. They agreed to share power in a rainbow coalition government of right-wing, centrist and left-wing parties whose overarching objective was to prevent Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, from reclaiming power.

Bennett, Israel’s thirteenth prime minister, held the post for almost a year, from June 13, 2021 until June 30, 2022. During this period, Lapid was alternate prime minister and foreign minister.

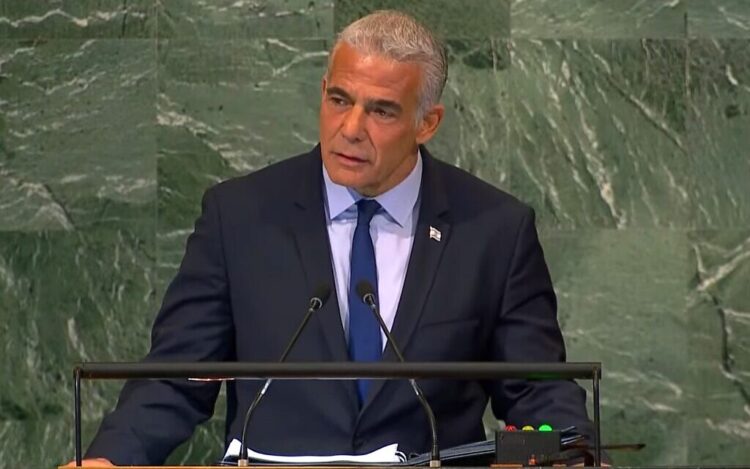

Bennett was succeeded by Yair Lapid, who assumed office on July 1. From that point onward, Bennett served as alternate prime minister until his resignation on November 8.

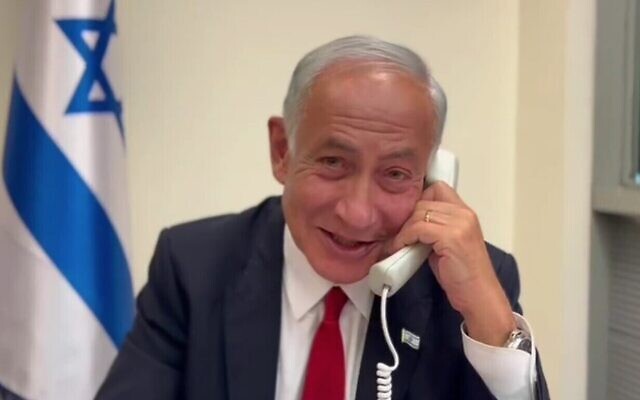

Lapid will cede his position to Netanyahu in the coming days, following Netanyahu’s announcement on December 21 that he has succeeded in forming a coalition government.

Netanyahu — Israel’s longest-serving leader — and his allies are back at the helm after winning a majority of Knesset seats in last November’s election.

Although the Bennett/Lapid interlude did not last long, it chalked up several major achievements.

Bennett and Lapid invited Mansour Abbas, the Israeli Arab leader of the Islamist Ra’am Party, to join the eight party coalition, and he accepted. It was the first time in Israeli history that an Arab party had been so integrated into Israel’s body politics.

Israel signed a historic maritime boundary agreement with Lebanon. Israel, too, reestablished diplomatic relations with Turkey.

Bennett and Lapid consolidated bilateral relations with three of the four Arab countries that normalized relations with Israel under the 2020 Abraham Accords.

As well, they improved Israel’s ties with Jordan and Egypt, which signed peace treaties with Israel in 1994 and 1979 respectively.

And they denounced the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, worked to sabotage Iranian nuclear sites, and continued to bomb Iran’s military bases in Syria.

One the other side of the ledger, Bennett and Lapid settled for the debilitating status quo with the Palestinians.

They did not enter into peace talks with the Palestinian Authority, which seeks statehood in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Neither Bennett nor Lapid were prepared to withdraw from the West Bank under a peace accord to end Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians. (Israel unilaterally pulled out of Gaza in 2005).

Nor were they willing to stop the expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, nearly two-thirds of which is fully occupied by Israel.

On the eve of the 2021 election, the fourth since 2019, Lapid and Bennett were adversaries. Lapid, a secular Jew, headed the Yesh Atid Party, which supports a two-state solution under certain conditions. Bennett, an Orthodox Jew who wears a yarmulke, was the leader of the Yamina Party, a champion of the settlement movement in the West Bank and an ardent opponent of Palestinian statehood.

Yesh Atid won a lot more Knesset seats than Yamina in the 2021 election, but in an extraordinary concession, Lapid agreed to let Bennett be prime minister in the first half of their term of office.

They recruited a wide array of parties into their coalition, from Gideon Saar’s right-wing New Hope Party to Nitzan Horowitz’s left-wing Meretz Party.

And they joined forces with Mansour Abbas, whose Ra’am Party defected from the Joint List of four Arab parties.

A pragmatist, Abbas was more interested in improving the material conditions of Israeli Arabs, who comprise 21 percent of Israel’s population, than in lobbying for a Palestinian state. Succumbing to his demands, the government allocated billions of dollars to upgrade the crumbling infrastructure of Arab villages and towns and to deal with the crime wave in the Arab sector.

Relying on the assistance of the United States and France, Israel managed to demarcate its maritime borders with Lebanon in the Mediterranean Sea, which holds rich deposits of natural gas. Israel’s agreement with Lebanon defused tensions, averted a possible war with Iranian surrogate Hezbollah, stabilized the region, and placed Lebanon and Israel on a far better economic footing. But it did not end Israel’s technical state of war with Lebanon.

After years of mutual acrimony, Israel and Turkey — the first Muslim nation to recognize the Jewish state — resumed formal diplomatic relations. Lapid flew to Ankara, where he met Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a fierce critic of Israel.

With visits to the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco, Bennett and Lapid broadened the Abraham Accords on political, economic and military levels.

The pair smoothed over relations with Jordan, which had grown testy in recent years, judging by the pronouncements of King Abdullah II. And they enhanced Israel’s economic relations with Egypt, which signed a gas export agreement with Israel last June.

Bennett and Lapid expanded Israel’s air campaign in Syria — Russia’s chief ally in the Arab world — to deal with Iran’s military entrenchment there.

Israel antagonized Russia by voting for United Nations resolutions condemning its invasion of Ukraine and by providing the Ukrainian government with humanitarian aid. These blips in Israel’s otherwise cordial relationship with Russia have apparently had no major adverse impact on its ability to carry out air operations against Iran in Syria.

In accordance with Israel’s previous policy, Bennett and Lapid continued to sabotage Iranian nuclear facilities. They opposed the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, from which the United States withdrew in 2018. In addition, they urged the Biden administration to walk away from talks in Vienna designed to revive it. At a minimum, they sought a stronger and longer agreement that would also require Iran to rein in its support for proxies like Hezbollah and Hamas.

Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz, the former chief of staff of the armed forces, attempted to improve Israel’s strained relations with the Palestinian Authority by means of economic concessions and talks with high-ranking officials and President Mahmoud Abbas. In their approach to the Palestinians, Bennett and Lapid essentially hewed to Netanyahu’s formula of conflict management rather than conflict resolution.

The Palestinian Authority played along, but complained that Israel offered no “political horizon,” or a plausible pathway to statehood.

Neither Bennett nor Lapid personally participated in this on-again, off-again process, but Lapid, in a speech at the United Nations, endorsed a two-state solution. Bennett stayed true to his hardline belief that a Palestinian state, however demilitarized, would not be in Israel’s strategic interests. And he supported the expansion of Israel settlements in the West Bank.

A wave of Palestinian terrorist attacks inside Israel starting last March prompted Bennett to order the first of many Israeli army raids into the northern West Bank to root out terrorism. Lapid emulated this policy.

Bennett and Lapid tried to tamp down border tensions with Hamas in the Gaza Strip by granting work permits to more Gazan laborers. The tactic has been fairly successful, but Israel’s dispute with Hamas is far from resolved.

In other words, the key problems that Israel faced during Netanyahu’s previous tenure still fester as he prepares to take office as Israel’s next prime minister.