Ady Walter’s cinematic portrayal of a shtetl in Ukraine before the Nazis and their collaborators murdered its Jewish inhabitants is heartwarming and heartbreaking. Shttl, a mostly black-and-white movie written and directed by Walter, is due to be screened on January 16 and 17 in its North American premiere at the New York Jewish Film Festival.

Haunting and elegiac, and unfolding largely in Yiddish with English subtitles, it occasionally bears a resemblance to a stark documentary.

Walter deliberately left out the letter “e” in shtetl to pay homage to the hundreds of thousands of Jews who lived in such “Fiddler on the Roof” villages in Eastern Europe prior to the Holocaust.

A Franco-Ukrainian production, Shttl was shot on location north of Kyiv several months before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2021. Shttl takes place almost entirely on June 21, 1941, the day before the German army attacked the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa.

During the first weeks and months of Germany’s military campaign, mobile killing squads, known as einsatzgruppen, accompanied the Wehrmacht in a murderous rampage during which communist officials and Jews were rounded up and summarily executed. In this fashion, approximately one million Soviet Jews were killed by firing squads in countless cities, towns and villages.

The first group of Jews to perish were from the western Ukrainian village of Sokal, near the Polish border. Sokal and other villages and towns in eastern Poland were occupied by the Red Army in September 1939 in line with the Soviet Union’s non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, which was signed about a week before the Wehrmacht invaded Poland.

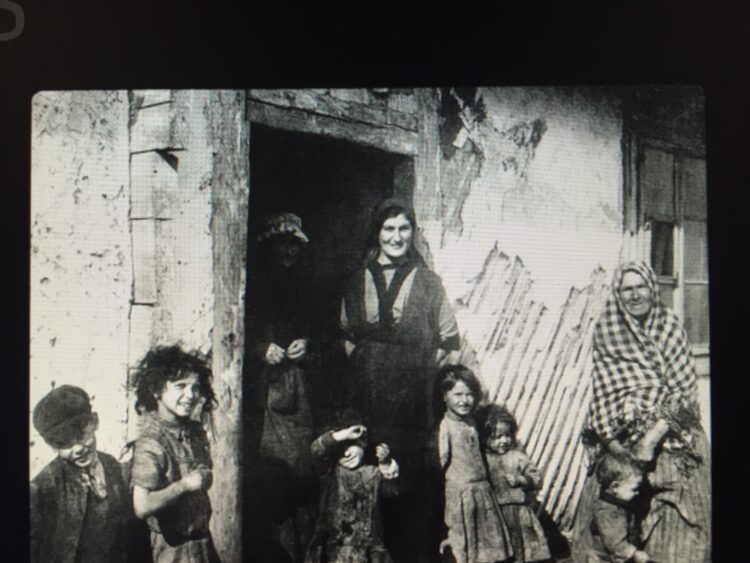

Although Sokal is initially singled out for attention in Shttl, the filmmakers say it is set in an “imaginary” Jewish village in Ukraine. This simple and remote village is populated by a mixture of Jews and Christians. In early scenes, the camera pans lovingly on a bustling market and several itinerant musicians.

The Red Army is still stationed there as Shttl begins. In an attempt to Sovietize it, the communist occupiers accentuate the evils of capitalism, but some people are clearly annoyed. “They are brainwashing us all day,” a woman complains.

Mendele (Moshe Lobel), a former resident of the village, is the movie’s central character. Once a yeshiva student and now an ardent communist, he works in a movie studio in Kyiv. He has returned to the village to see his father (Saul Rubinek), an ultra-Orthodox Jew from whom he is estranged, and his girlfriend, Yuna (Anisia Stasevich), the daughter of the local rabbi.

Mendele and Yuna are deeply in love, share the same progressive ideas and dreams, and intend to get married. But Folye (Kostiantyn Afanasiev), a pious Jew whose beliefs and lifestyle are inextricably enmeshed in Orthodox Judaism, also wishes to marry Yuna and already has obtained her father’s approval.

To his traditional father, Mendele is a renegade and a luftmensch who can only redeem himself if he resumes his Torah studies and moves back to the village. Mendele has no such intentions. He has cut himself off from it, though he still has a foot in the door of his Jewish upbringing and mourns and misses his late mother, who adored and completely understood him.

Walter, in deft strokes, telegraphs the imminent Nazi storm and the burdens of the Soviet occupation.

A Jewish chess player, whose odd behavior brands him as a deviant, predicts that the apocalypse is on the horizon. No one, including Mendele, listens to him. Who could have known that the Germans would expand the Holocaust into the Soviet Union?

Folye, in the meantime, fears that the atheistic Soviets will close synagogues, while a few boys spread the news that yeshivas are being shuttered. By way of juxtaposition, a Red Army officer exhorts Jews to leave the spirit of the shtetl behind them, build the Soviet motherland, and tap into the teachings of Lenin and Stalin.

As Mendele and a local Jew walk quietly in the woods, they hear explosions and gunfire in the distance. The implicit message is that the Germans are coming.

Although Mendele has jettisoned Orthodox Judaism, he still has a soft spot for it. When he wanders into a wooden synagogue, the village rabbi greets him warmly. Being fond of Mendele, he understands why he “grazes in strange fields.”

Later, in an impassioned debate involving several villagers, the issue of immigration to Palestine is raised. The rabbi rushes to Mendele’s defence and declares that Jews must unite as their hour of peril approaches. The conversation intensifies as the rabbi argues that evil can only be combated by godly faith. Mendele disagrees, saying that Amalek, an indirect reference to the Nazis, should be confronted with arms.

As Shttl winds to a close, high drama reigns. Mendele’s father makes a last-ditch effort to woo him back to his religious roots. Folye accuses Mendele of being a heathen and a gentile. Demyan, Mendele’s Christian friend, cleverly lures Yuna out of her house so that she can be united with Mendele.

The threesome escape into the woods, but danger lurks. German soldiers are edging closer to the village. What should they do?

We now know that the arrival of the 17th Wehrmacht army spelled the beginning of the end of this shtetl. Shttl omits the salient fact that Ukrainian police in the service of the Germans were the first to kill its Jewish residents. The Nazis eventually participated directly in the murder of its Jewish inhabitants, thereby obliterating a world that no longer exists.

Shttl resurrects it with love and respect.