Conspiracy theories have spanned the centuries, feeding human impulses like jealousy, anger, insecurity and fear and often causing needless death and destruction.

This explosive topic is explored in “Conspiracy,” the first episode of Lewis Cohen’s Truth & Lies, a six-part television series on TVO and tvo.org that starts on January 17 at 9 p.m. and runs weekly until February 21. These lively programs examine the deceptions and half-truths that have perpetuated toxic hatreds, caused the death of multitudes in wars, and toppled empires.

“Conspiracy” begins in present-day China, migrates to medieval and contemporary Europe, and ends in the United States during the presidency of Donald Trump, a conspiracy theorist himself.

Several European historians offer succinct commentaries on the topics at hand.

Miri Rubin, a professor of medieval and early modern history at Queen Mary University in London, discusses the infamous William of Norwich blood libel case. Michael Butter, a cultural historian at the University of Tubingen in Germany, analyzes American conspiracy theories, as does Nancy Rosenbaum, a Harvard University scholar. Michael Hagemeister, another German historian, delves into The Protocols of the Elders a Zion, the consummate expression of a conspiracy theory steeped in antisemitism.

“Conspiracy theories make the world meaningful, they imagine a world where nothing happens by accident,” says Butter. “A world without chaos. A world where everything has been planned and everything is controlled.”

As the Covid-19 pandemic spread across the globe from China, decimating lives and routines, conspiracy theorists spun all manner of explanations about its origins. Some went as far as to brand the virus as a Chinese bioweapon.

Such accusations were hardly surprising, since they arise from a human compulsion to detect patterns and links in history.

In 1144, a 12-year-old British boy named William of Norwich was found murdered, his body riven by strange wounds. His uncle, a local priest, compared William to Jesus and blamed Jews for his death. The accusation gained more credence when Thomas of Monmouth, a monk, wrote a book about the incident, The Life and Passion of William of Norwich.

Monmouth’s horrific calumny, which had no basis in fact, gained currency in France, Switzerland, Spain, the German states and Russia, causing the deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of Jews.

When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died prematurely in 1791 at the age of 35, his admirers sought answers. Some believed he was killed by his lover’s husband. Still others thought that Mozart was murdered because the authorities resented his membership in the Free Mason movement, which advocated societal change. Two years after his passing, masonic lodges in the Austro-Hungarian empire were closed.

With the fall of the Romanov dynasty in Russia, sales of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion — a czarist forgery which postulated that Jews sought world domination — took off. The presence of Jews like Leon Trotsky in the leadership of the Soviet Union was proof to antisemitic conspiracy theorists that a Jewish cabal bent on global hegemony in fact existed.

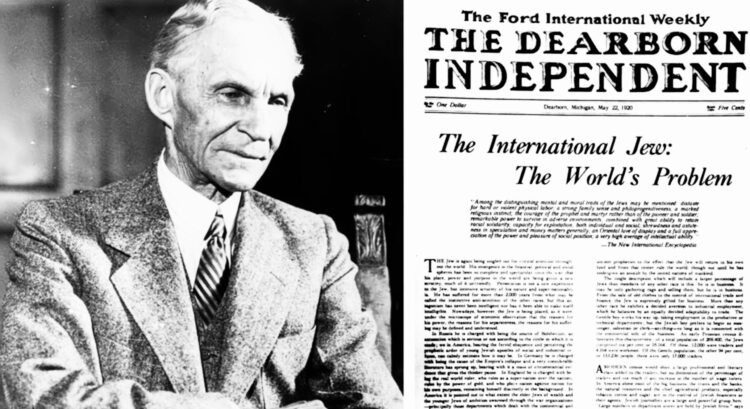

Henry Ford, the American automobile manufacturer, bought into these ideas and disseminated them in the pages of his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, under the headline of “The International Jew.”

Adolf Hitler, the German chancellor, voiced admiration for Ford, and the Protocols became a major propaganda tool for the Nazis, which imposed a reign of terror on German Jews.

The assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1963 sparked a succession of conspiracy theories. A special presidential commission concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole assassin, but conspiratorial minds were convinced that there was a second gunman.

A golden age of conspiracy theories dawned before and after Trump’s election.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton, Trump’s opponent, was accused of running a child porn ring from a pizza parlor. Trump, who had questioned whether his predecessor, Barack Obama, was American born, claimed that Clinton was plotting with international. bankers to destroy the United States.

According to Butter, 50 percent of Americans are drawn to at least one conspiracy theory. One of the biggest ones, created and circulated by Q-Anon, propagated the allegation that the U.S. is run by the “deep state,” a shadow government. Trump’s unfounded claim that he won the last presidential election also falls into the realm of conspiracy theory.

Cohen contends that conspiracy theories, once the preserve of elites, have become a tool of the powerless. Be that as its may, conspiracy theories are still in vogue, nearly one thousand years after the demise of William of Norwich.