The release of Kjell Grede’s feature film, Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, was unfortunately timed, having come out in the same year as Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. Which meant, in hindsight, that it was drowned out by the sheer power and popularity of Spielberg’s epic movie, the recipient of seven Academy Awards, including best picture.

Both films are about the Holocaust. While Schindler’s List is set in Poland, where three million Jews perished during the Nazi occupation, Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg takes place in Hungary, where the Germans committed their final genocidal atrocity on a grand scale.

Righteous gentiles are at the core of each film.

Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist based in Krakow, was instrumental in the rescue of some 1,200 Polish Jews. By employing them in his factory, he saved lives.

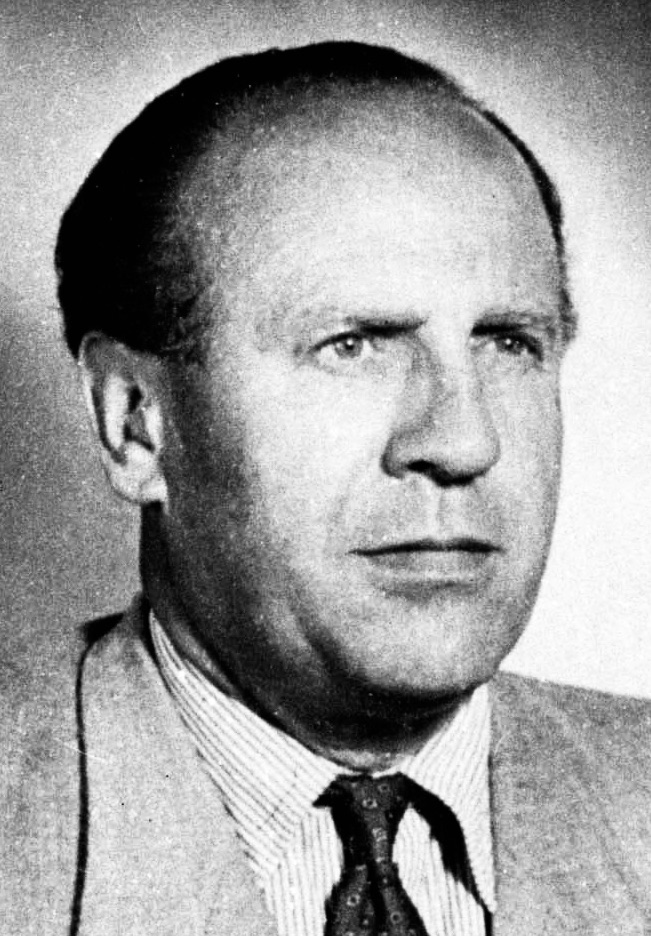

Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish businessman from a wealthy banking family, arrived in Budapest in July 1944 in a bid to save a Hungarian Jewish community that was all but obliterated within a matter of months by the Nazis and their Hungarian collaborators. The survivors of this carnage, who lived in Budapest, owe their lives to Wallenberg’s humanity, courage, fortitude and persistence.

Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, which is currently being presented online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, stars Stellan Skarsgard as Wallenberg.

Relentlessly dark and grim, the movie opens in 1943 as Wallenberg — an importer of Hungarian and German delicacies — gazes out the window of a passenger train passing through central Europe. Attendants suddenly draw the shades, but Wallenberg catches a glimpse of a terrible scene on another railway track. Unidentified soldiers are throwing corpses out of freight cars, and a man and his son who have managed to escape are summarily shot. Presumably, the victims are Jews.

The scene shifts to Stockholm, Sweden’s capital, in June 1944. Wallenberg is being interviewed for a humanitarian position in Budapest created by the War Refugee Board, a new American agency whose objective is to help Jews caught in the Nazi net of destruction. A rabbi questioning him doubts whether he’s fit for the post and can survive it. To which Wallenberg replies, “This will be the only real thing I will do.”

Wallenberg, then in his early thirties, was accredited as a diplomat to the Swedish legation in Budapest. At that point in the war, Sweden was still a neutral country. Once in Budapest, he made himself indispensable by distributing life-saving passes to Jews that Germany and its ally, Hungary, honored, and by establishing safe houses where Jews could shelter in place.

The film, which unfolds in Swedish, German and Hungarian and is set to a somber musical score, focuses on the period from December 1944 onward. By that time, more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews had been murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland.

As he makes his rounds, he visits a safe house, urging its frightened occupants to remain calm. In quick succession, he saves a group of Jews huddled in a train, talks to a distraught mother whose daughter has disappeared, chats with a young couple who want to be married, and tries to intervene in a Hungarian police roundup of Jews.

Visiting the Nazi-appointed Jewish Council, he learns that Budapest’s remaining 65,000 Jews are in dire danger. Wallenberg speaks to Adolf Eichmann, the German official in charge of the Final Solution of Jews. He confirms that Jews in the city are doomed and warns Wallenberg to terminate his mission. As they speak, the Red Army is converging on Budapest.

Despite the dramatic situation, this highly stylized film strangely lacks tension. It is also bereft of historical context.

By now, Hungary is ruled by the Arrow Cross fascist movement, which intends to murder the last surviving Jews of Hungary. Wallenberg himself has been targeted by the Arrow Cross, but he goes about his business with steely determination. Skarsgard is quite impressive in his role.

True to its antisemitic fanaticism, the Arrow Cross launches a raid into the ghetto and starts dumping slain Jews into the Danube River. Wallenberg’s confrontations with Arrow Cross officials are curt and unpleasant.

Swedish diplomats order him to leave, but he decides to remain in Budapest, much to his detriment. Soviet occupation forces, regarding him as a Western capitalist spy, arrested him on January 17, 1945, and he was never seen again.

This appalling miscarriage of justice is underscored in Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, which commemorates a man of sterling character and high moral principles.