Hal Wallis, the prolific American producer whose movies ran the gamut from Casablanca and The Life of Emile Zola to The Adventures of Robin Hood and True Grit, was an accidental Hollywood luminary, as we learn in Bernard F. Dick’s thorough biography, Hal Wallis: Producer to the Stars, published by University Press of Kentucky.

Wallis, based in Chicago, was selling stoves for the Hughes Electric Heating Company when fate intervened. His sickly mother, having been afflicted by tuberculosis, required a change in climate, forcing the Wallis family to move to Los Angeles. His older sister, Minna, who happened to be movie mogul Jack Warner’s secretary, found him a job managing one of her boss’ theaters in the city.

These serendipitous developments augured well for Wallis, who went on to become one of the most successful producers in the film industry. His rise to fame is meticulously traced by Dick — a professor emeritus in communications and English at Fairleigh Dickinson University — in this deeply-researched and informative volume.

Wallis was born in Chicago in 1898, the son of Jacob and Eva Walinsky, Jewish immigrants from the Eastern European cities of Minsk and Kovno. A tailor by trade and a gambler by addiction, Jacob abandoned his family in 1912 and went to Canada, where he died in 1930.

Wallis earned a diploma in typing and shorthand at a stenographic school and became a $50-a-week travelling sales representative. Minna, who would forge a career as a powerful Hollywood talent agent, believed her younger brother was meant for something better than selling stoves. She introduced him to Sam Warner, who was in charge of the Warners’ growing theater chain. Warner was impressed by Wallis, hiring him as a publicist. “In one sense, movies were not that different from electric ranges,” writes Dick. “Every commodity requires promotion.”

This job led to a similar position with Sol Lesser, the proprietor of a theater chain and the producer of a succession of Tarzan films.

Minna, in the meantime, discovered an unknown actor named Clark Gable, who would be her first client and probably her lover as well. Her other clients included Myrna Loy, John Barrymore, Errol Flynn and George Brent.

Wallis’ career took an upward turn when he went into production at First National Pictures, which was mostly owned by the Warner brothers. He worked under the supervision of Darryl Zanuck, whom he would replace after his resignation in 1933.

As Dick points out, Wallis climbed the greasy ladder of success despite his lack of social graces and his dislike for schmoozing. These deficiencies could be ignored because he had a knack for finding talented new faces.

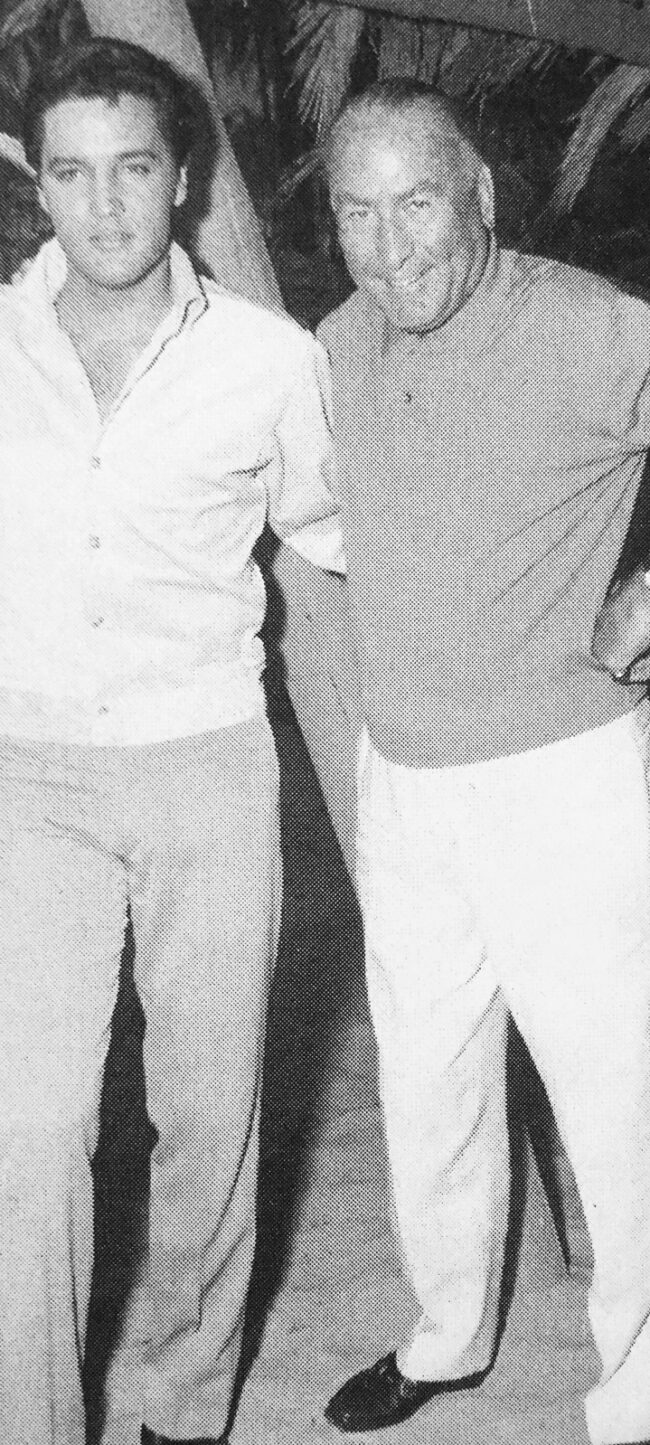

Among the actors he discovered were Edward G. Robinson, whose appearance in Little Caesar spawned Warner’s gangster movies, and Burt Lancaster, who shot to stardom with The Killers (1946) and Brute Force (1947). Wallis is also credited with signing up Lauren Bacall, Kirk Douglas, Charlton Heston, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis and Elvis Presley.

As Dick suggests, Wallis was a hard taskmaster. He could become testy if his instructions were ignored. And he bemoaned sloppy diction from actors. “Nothing escaped Wallis’ attention,” says Dick, who argues that he hit his peak in the early 1940s after receiving the Irving Thalberg Memorial Award in 1939.

That was a banner year for Wallis, whose films were nominated for Oscars in almost every category. They included Jezebel, Four Daughters, Angels With Dirty Faces, The Adventures of Robin Hood and Confessions Of A Nazi Spy, the first major expose of German espionage in the United States.

Two years later, he produced High Sierra, which transformed Humphrey Bogart into a star and Ida Lupino into a respected actress and later one of Hollywood’s few female directors.

In 1942, Wallis signed a lucrative contract with the Warners stipulating that he could produce four films of his choice a year, and that he would receive 10 percent of the profits after a certain fiscal point.

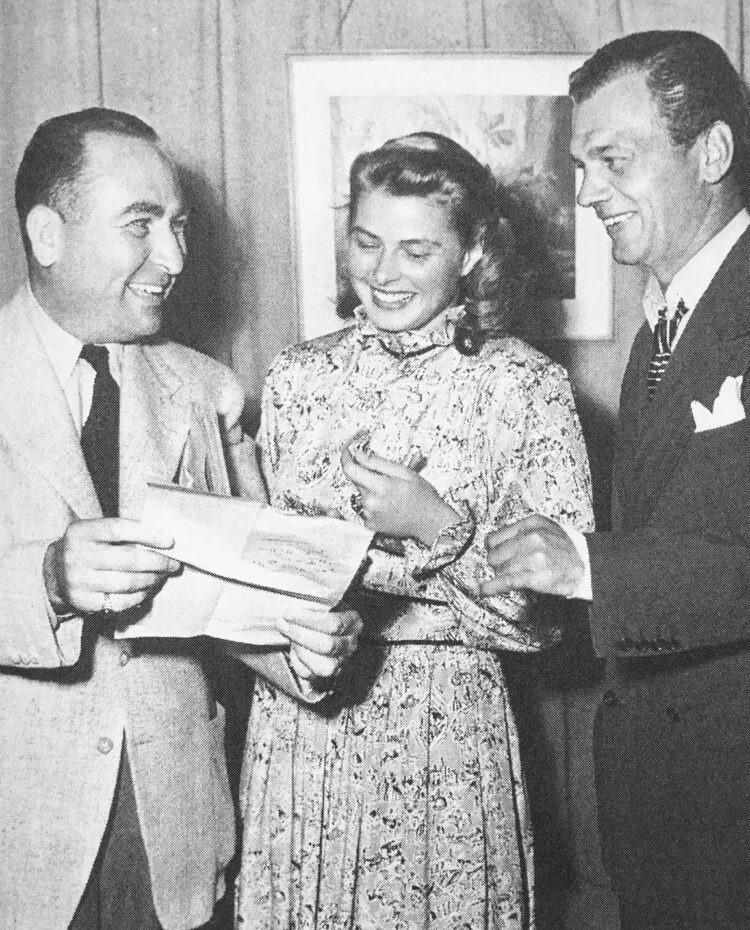

Dick claims that Casablanca, directed by Michael Curtiz and released in January 1943, was “the only film that either of them made that found a permanent place in both American mythology and world cinema.” According to Dick, it was Wallis who changed its original title, Everybody Comes To Rick’s, to Casablanca.

Dick discloses that Curtiz, a Hungarian Jew, was Wallis’ favorite director. Together they made more than 20 films, notably The Charge of the Light Brigade, Captain Blood, Santa Fe Trail, Yankee Doodle Dandy and This Is The Army.

Although Casablanca was strictly Wallis’ picture, Jack Warner, the narcissistic head of the studio, upstaged Wallis when he beat him to the stage to accept the Academy Award for best movie. Wallis’ relationship with Warner deteriorated after that embarrassing incident. As Dick observes, “By 1944, Warner seemed to be doing everything in his power to make Wallis’ life so unpleasant that he would eventually leave the studio.”

Wallis’ last film, Rooster Cogburn (1975), was also one of his happiest experiences in 40 years in cinema. “Much of it had to do with Katherine Hepburn, who became a true friend, one of the few who understood his ways.” Their friendship, he adds, was “one of soul mates.”

“One suspects that Wallis secretly admired Hepburn’s individualism that flew in the face of Hollywood protocol, because he too wished he could stay home on Oscar nights, pass up the obligatory banquets, and avoid the discomfort of interviews,” he goes on to say. “But what really drew him to Hepburn was the sense of privacy that they shared.”

Wallis, diagnosed as a diabetic, succumbed to the dreaded disease after some of his toes and left foot were amputated. He died on October 6, 1986. Minna, his sister, had passed away two months earlier.

At the insistence of his wife, the actress Martha Hyer, Wallis was sent to the next world in a simple, dignified service. “He received a memorial that, by Hollywood standards, was the epitome of taste,” writes Dick. “No autograph hounds, stars hogging the spotlight … or reporters asking for sound bytes to sum up a career that lasted almost half a century.”

Ultimately, Wallis’ films, some of which are truly memorable and continue to stand the test of time, are his lasting memorial.