Hebron, with population 250,000, is the largest Palestinian city in the West Bank containing a Jewish community. The 800 Jews of Hebron are religious nationalists and live along the length of Shuhada Street, barely coexisting with their Palestinian neighbors and protected by a phalanx of Israeli soldiers.

Their small urban enclave, known as H2 under the 1997 Hebron agreement signed by Israel and the Palestinian Authority, is cut off from the rest of Hebron, which is exclusively inhabited by Palestinian Arabs and commonly referred to as H1.

As Israeli human rights lawyer Michael Sfrad observes in H2: The Occupation Lab, a thoughtful documentary directed by Idit Avraham and Noam Sheizaf, Hebron is vividly symbolic of Israel’s 56-year occupation of the West Bank. Their movie will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on June 4.

“Everything Israel does in the West Bank began as trial and error in Hebron,” says Sfrad.

The army patrols, the road blocks, the check points, the curfews, the separate roads, the closures, and the facial recognition technology, all intended to consolidate Israel’s grip on the West Bank, were initially tested in Hebron.

To Jews and Arabs, Hebron is vitally important from religious and historic perspectives.

Abraham, their common ancestor, frequented the Cave of the Patriarchs, which has been a mosque and a Jewish place of prayer since Israel’s conquest of Hebron in the 1967 Six Day War. Until then, Jews were apparently not permitted to walk past its seventh step.

Hebron, too, is the site of an ancient Jewish community, which was destroyed during a 1929 Arab pogrom resulting in the deaths of 67 Jews. In the wake of the Six Day War, Israeli Jews settled in Hebron and reclaimed buildings that had belonged to their ancestors. To Palestinians like Issa Amro, who was born in Hebron and conducts tours of it, the Jewish resettlement has been a fraught process.

Shlomo Gazit, the first Israeli military governor of the occupied territories, justifies Israel’s expansionist policy in the West Bank. “We weren’t the first nor the last state to occupy a territory and hoping to hold on to it.”

Israel’s first major problem in Hebron revolved around the Cave of the Patriarchs, he adds. Israel was obliged to respect its status as a mosque while allowing Jews to pray there at different hours. Moshe Dayan, the then Israeli defence minister, worked out an arrangement with the mayor of Hebron, Sheikh Mohammed Ja’abari, in exchange for softening the impact of the occupation.

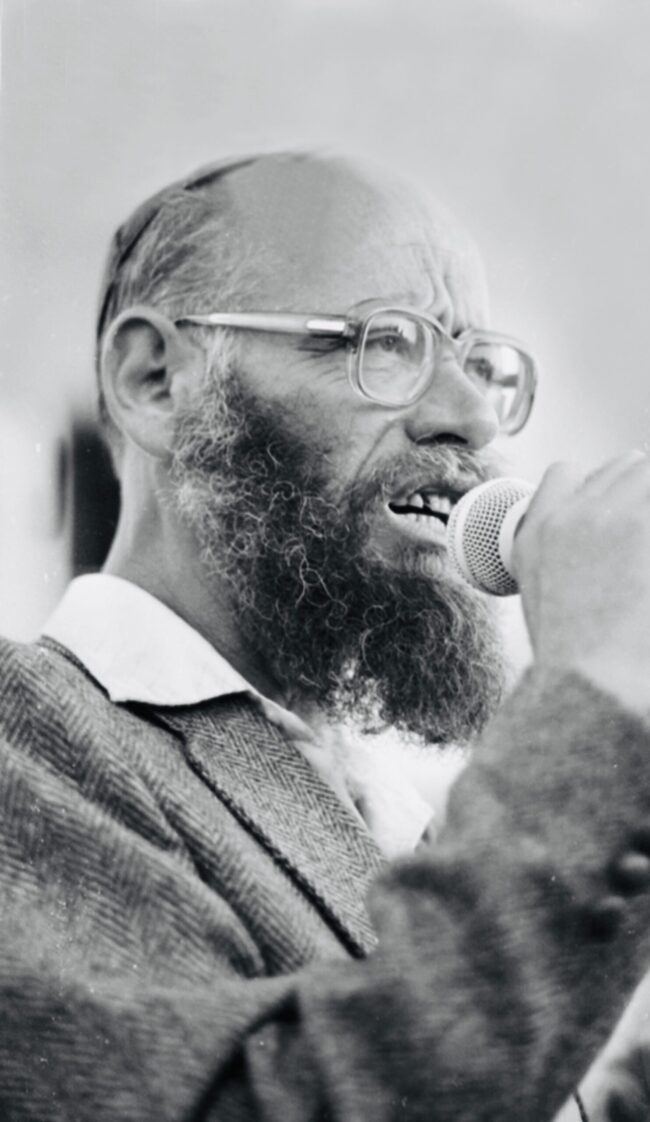

The first group of Jews to settle in Hebron arrived in 1968 under false pretences and under the leadership of Rabbi Moshe Levinger, who mistakenly believed that Jewish settlement in the West Bank enhanced Israel’s security. He created a “new reality” in Hebron that the Israeli government eventually embraced.

Subsequently, Israel built the suburb of Kiryat Arba in the greater Hebron area. It was constructed on land owned by Ja’abari, who thought that a handful of Jewish families would pose no existential threat to the Palestinians. Little did he know that Kiryat Arba would flourish and expand by leaps and bounds.

Israel did everything in its power to perpetuate Ja’abari’s mayoralty, going as far as to deport one of his opponents to Lebanon. Nonetheless, he lost the municipal election. His creative and successful successor, Fahad Qawasmi, was similarly subjected to deportation.

In a turning point, Israeli settlers broke into Hadassah House, a Jewish property in what would be H2 in Hebron. Palestinians regarded the incident as a provocation, since Israeli governments since 1949 have denied Palestinian refugees the right to return to their ancestral lands inside Israel.

From that point onward, Jews streamed into Hebron on an accelerated basis. Ariel Sharon, an Israeli defence minister, proclaimed that Jews have a right to live anywhere in the biblical Land of Israel.

With the outbreak of the first Palestinian uprising in 1987, Israel bolstered its military presence in Hebron and imposed restrictions on its Arab residents, causing further unrest among Palestinians.

Tensions soared to unprecedented heights in 1994 after Baruch Goldstein, a U.S.-born settler, fatally shot 29 Palestinians in the Cave of the Patriarchs. Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s prime minister, apparently considered expelling Jews from Hebron, but he refrained from doing so.

The second intifada, which erupted in 2000, exacerbated tensions in Hebron, as did an incident in 2016 during which an Israeli soldier, Elor Azaria, killed a Palestinian in the center of the city.

Hebron is certainly a flashpoint in Israel’s struggle with the Palestinians. H2: The Occupation Lab illustrates this point graphically.