Recep Tayyip Erdogan is back in the saddle again after winning his third five-year term as president of Turkey.

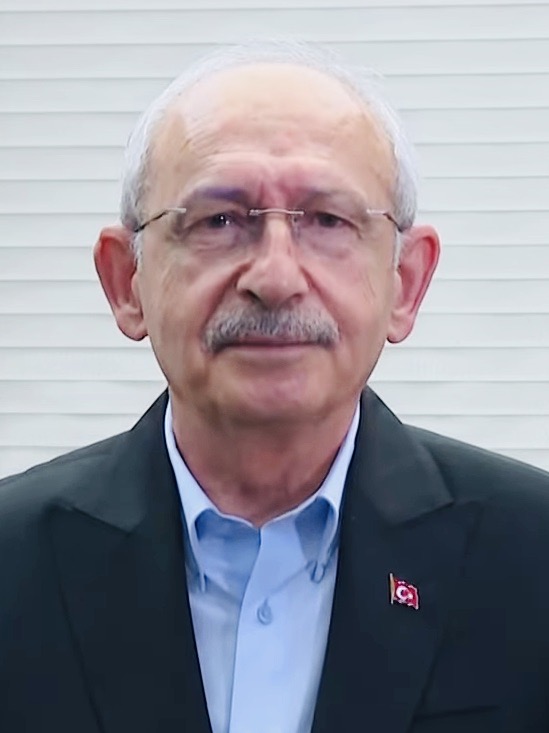

In a runoff election on May 28, widely regarded as a referendum on his 20-year reign as Turkey’s dominant politician, he handily defeated challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu by a margin of 52.1 percent to 47.9 percent.

“We will be ruling the country for the coming five years,” Erdogan told supporters in his home district in Istanbul.

The runoff was called after Erdogan failed to win an outright majority in the first round on May 14, winning 49.5 percent of the votes compared to 44.9 percent for Kilicdaroglu, a 74-year-old retired civil servant.

Observers expected Erdogan to prevail after the third-place candidate in the first round, Sinan Ogan, threw his support behind him on May 23.

Erdogan, 69, and his Islamist Justice and Development Party coasted to victory despite Turkey’s economic woes and his government’s complicity in the deaths of more than 50,000 Turks who were killed when their high-rise apartment flats were levelled by last winter’s massive earthquake.

Inflation in 2022 soared beyond the 80 percent mark, greatly eroding the purchasing power of most Turks. And in the wake of the earthquake, critics accused the government of tolerating the shoddy construction methods that contributed to the inordinately high death toll.

To his conservative and religious supporters, mainly in Anatolia, Erdogan’s glaring deficiencies could be sloughed off because he had lifted many of them out of poverty since becoming prime minister in 2003.

Erdogan’s nation-wide infrastructure projects, intended to modernize Turkey, were equally popular with his base.

They also liked his success in curbing the power of the secular elite, which ruled Turkey from its founding in 1923 until the late 1990s, but is still quite powerful.

Under Erdogan’s direction, the ban on women’s head scarves in state offices was lifted, while a host of mosques were built across the country. Several years ago, he transformed Hagia Sofia, a major tourist attraction in Istanbul, from a museum into a mosque.

In short, Erdogan expanded the role of Islam in public life.

A populist and a pious Muslim who tends to be combative, provocative and prickly, Erdogan gained national recognition in 1998 when, as mayor of Istanbul, he recited a 1920s Islamic poem calling for a religious revolt in Turkey, the successor state of the Ottoman empire. Sentenced to ten months in prison and slapped with a lifetime ban on political activity, he was released after four months.

In 2002, the Constitutional Court lifted the ban, enabling Erdogan to play a pivotal role in the success of the Justice and Development Party.

Erdogan became Turkey’s first popularity elected president in 2014 and proceeded to maximize his powers by abolishing the post of prime minister, imposing a veto on parliamentary legislation, and giving himself the right to appoint judges.

In a daring coup attempt, disaffected army and air force officers and followers of exiled Islamic leader Fethullah Gulen attempted to oust Erdogan in 2016. Having ruthlessly crushed the rebellion, Erdogan proceeded to restrict democratic rights and purge the armed forces, the judiciary, police departments, newspapers and magazines, and university faculties of unreliable and undesirable elements. As well, he announced restrictions on the internet.

To his enemies, the purge was reminiscent of Joseph Stalin’s crackdown on ideological rivals in the 1930s and was nothing less than a thinly-disguised ploy to silence his secular opponents and push Turkey toward one-man rule.

As a result of his authoritarian policies, which diverge from Western values such as the rule of law and freedom of the press, Turkey’s efforts to join the European Union have been dashed.

With respect to foreign policy, Erdogan has adopted a non-aligned position, even though Turkey — a strategic bridge between Europe and the Middle East — is a member of NATO, the Western military alliance that was designed to contain communism and the former Soviet Union.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Turkey has consolidated its bilateral relations with Moscow and hampered NATO’s ambition to expand its membership.

Erdogan condemned the invasion, but has since refused to enforce Western sanctions on Russia, thereby helping Russian President Vladimir Putin finance his war of aggression and stave off complete economic isolation.

Turkey and Russia have expanded the volume of their trade, and Russia is currently building Turkey’s first nuclear power plant and planning to make Turkey a hub of its natural gas trade.

With Putin’s consent, Erdogan was instrumental in brokering an agreement to allow for the export of Ukrainian grain from the Black Sea port of Odessa.

On the other hand, much to Russia’s indignation, Turkey has sold armed drones to Ukraine and has backed different sides in the conflicts in Syria and Libya. In 2015, Turkey downed a Russian fighter jet over its territory, ushering in an unusually tense period in its relationship with Russia.

Erdogan belatedly supported Finland’s application to join NATO, but has blocked Sweden’s entry into the alliance due to its refusal to imprison or deport Kurdish refugees who belong to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which Turkey and the United States have condemned as a terrorist organization.

Erdogan’s relations with the United States have been tense since it removed Turkey from a program to buy F-35 fighter jets in retaliation for its purchase of an air-defence system from Russia.

Erdogan, too, has blasted the United States for working with a Syrian Kurdish militia in Syria that, Turkey claims, is associated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party.

In the past year, Erdogan has patched up relations with Israel, one of Turkey’s geopolitical rivals, and has attempted to improve ties with Syria and Egypt.

Erdogan remains a champion of the Palestinian cause and a supporter of Hamas, but of late he has toned down his critique of Israel’s policy toward the Palestinians.

On another front, Turkey is embroiled in a dispute with Greece, its old nemesis, over gas deposits in the Aegean Sea. Turkey is also enmeshed in a conflict with Cyprus following Erdogan’s advocacy of a two-state solution on that island, part of which Turkey has occupied since its 1974 invasion.

It’s clear that Turkey’s ambition to enjoy problem-free relations with its neighbors is still a pipe dream.