As eye-catching symbols go, the swastika has been extremely problematic and highly offensive to many people for about a century. An ancient religious and cultural sign of good fortune and prosperity among Hindus, Jains and Zoroastrians, it was brazenly appropriated by the Nazi Party in Germany and willfully converted into a striking symbol of race hatred and racial superiority.

Of late, the unfortunate entanglement of the swastika with Adolf Hitler’s genocidal regime has caused quite a stir in the western U.S. state of Wyoming.

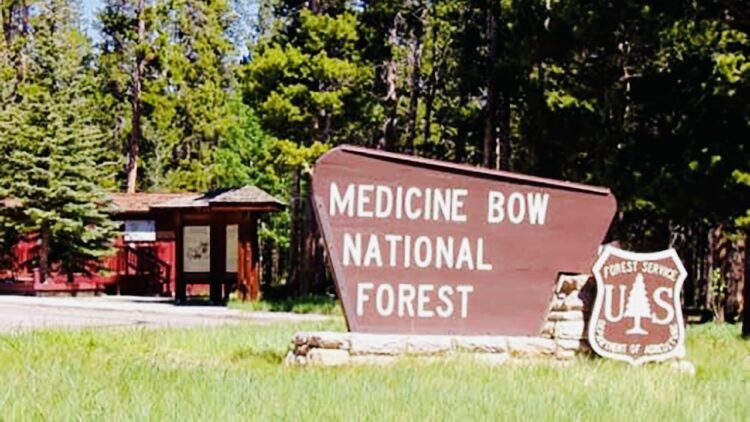

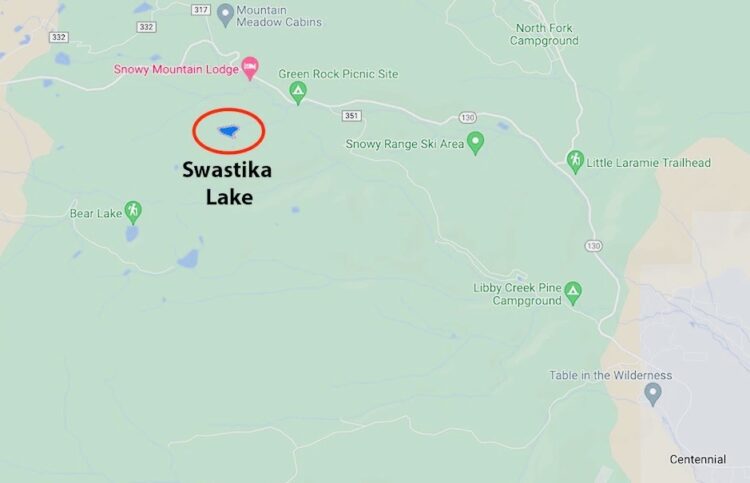

More than a century ago, a decade before Hitler was appointed Germany’s chancellor, a small and remote body of water in the state’s Medicine Bow National Forest was dubbed Swastika Lake. A nearby ranch and a general store adopted this name as well.

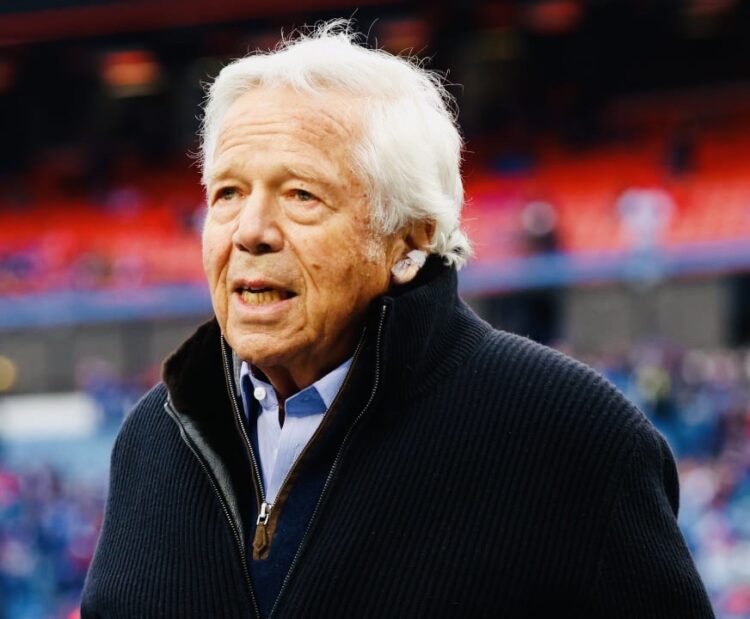

The lake, west of the town of Laramie, is a glistening marvel of nature, but its name offended Lindsy Sanders, a local resident, and Robert Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots football team and the chairman of the Foundation To Combat Antisemitism.

Two months ago, Sanders asked the U.S. Board on Geographic Names to rename it to Fortune Lake, in keeping with the historical, pre-Nazi meaning of the swastika. She explained that Swastika Lake had a jarring ring to it that is “so painful to so many people.”

Kraft, in a letter to the Albany County Board of Commissioners, urged its three members support Sanders’ recommendation on the grounds that the swastika glorifies the Nazis and, in effect, legitimizes the Nazi persecution and mass murder of Jews.

As he wrote, “While we appreciate the history and original meaning of the swastika symbol, it has unfortunately become synonymous with one of the greatest atrocities in human history. Although the name of Swastika Lake precedes the rise of the Nazi Party, the symbol today … serves as a traumatic and painful reminder of the Holocaust for Jewish people and all communities that were victims of the Holocaust …”

Kraft also pointed out that the swastika is used by white supremacists and neo-Nazis to glorify Nazi Germany and promote hatred of Jews.

“We urge you to stand beside the Jewish people and rename Swastika Lake so as not to contribute to the retraumatization of many Jewish people and members of other communities across the United States who were victimized by the Nazis.”

Kraft reminded the commissioners that place names in the United States are commonly altered, saying that Swastika Mountain in Oregon was recently changed to Mount Hale.

Thankfully, Kraft’s plea did not fall on deaf ears.

On June 21, two of the three commissioners, Pete Gosar and Sue Ibarra, voted to rename Swastika Lake in honor of Samuel Knight, a renowned local geologist and palaeontologist and the founder of the University of Wyoming Science Camp, which is near Swastika Lake.

In supporting this belated motion, Gosar argued that the swastika’s negative connotation overwhelmingly outweighs its positive original use. “Millions of people lost their lives under that symbol,” he said, adding that American army veterans of World War II, including his late uncle, laid down their lives to eradicate the Third Reich.

Kim Viner, the secretary of Laramie’s Historical Society, came out in favor of their decision.

The sole holdout, Terri Jones, claimed that Swastika Lake’s name should be preserved in the interests of combating the evils of antisemitism and Nazism.

Her argument was, in a word, silly.

Names inextricably associated with the symbols of the most monstrous regime of the twentieth century should be banned for obvious reasons. Yet it is most unfortunate that the Asian swastika, a symbol of well-being for centuries, has been so badly and irrevocably maligned in the process.