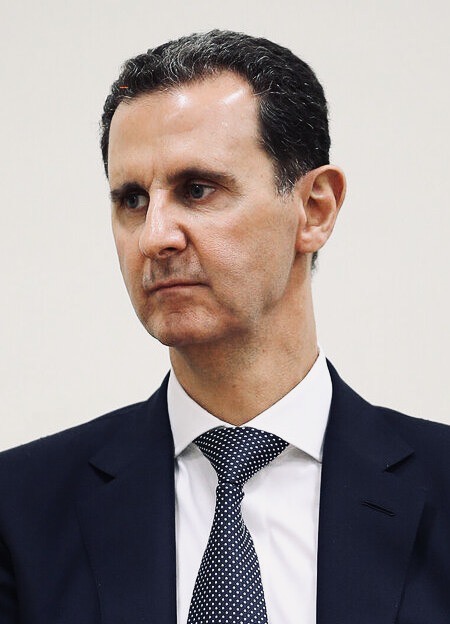

The Syrian government recently revoked the British Broadcast Corporation’s media accreditation after it published a disturbing report delineating the incriminating links between the illegal Captagon drug trade, President Bashar al-Assad and his family, and Syria’s armed forces.

The Syrian Ministry of Information denounced the BBC report as “biased and misleading … based on statements from terrorist entities and those hostile to Syria.”

Syria stoutly denies any involvement in the trade, but its denials are extremely suspect and implausible.

The United States, Britain and the European Union have accused Syria and its regional allies, including Hezbollah, of producing and distributing Captagon pills, which are manufactured in Syria and, to a much lesser extent, in Lebanon.

Last year, the United States passed the Captagon Act, which links the trade to Syria and describes it a “transnational security threat.”

Syria, the so-called beating heart of Arab nationalism and a major foe of Israel, has degenerated into a narco state.

Captagon, a highly addictive amphetamine that has plagued the Middle East since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, has been used to treat attention deficit disorder and narcolepsy, but it has also been misused as a central nervous system stimulant.

The production and smuggling of Captagon have generated immense wealth for Assad, his associates and allies, and given Syria an economic lifeline. By one estimate, the Captagon retail trade was worth $5.7 billion in 2021. Much of it is centered in Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and the Gulf states.

Hundreds of millions of these little white pills have been smuggled into these Arab countries, but some shipments have been intercepted by Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

Six months ago, Jordanian soldiers killed 27 suspected smugglers in a gun battle near the Syrian border. In 2021, the Lebanese businessman Hassan Daqqou, dubbed the “King of Captagon,” was convicted and found guilty of drug trafficking. His shipment of nearly 100 million Captagon pills, with an estimated street value of about $1.5 billion, was destined for Saudi Arabia.

Syria turned to the lucrative Captagon trade after Western countries imposed stiff economic sanctions on Assad’s dictatorial regime following the outbreak of the civil war, which has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Syrians and displaced about half of Syria’s population. This bitter conflict still rages despite Syria’s success in recapturing land initially seized by Syrian rebels and Islamic State forces.

Joel Rayburn, a former U.S. special envoy to Syria, told the BBC that the Syrian regime has become increasingly reliant on Captagon as a prime source of income. “The scale of the revenues … dwarfs the Syrian state budget,” he said. “If the Captagon revenues were stopped or seriously disrupted, I don’t think the Assad regime could survive that.”

According to a report issued by the New Lines Institute, the Syrian government uses “local alliance structures” and armed groups, such as Hezbollah, “for technical and logistical support in Captagon production and trafficking.”

Assad’s younger brother, Maher, the commander of the Fourth Division, an elite Syrian army unit responsible for protecting the regime, has been implicated in the illicit Captagon trade. He was subjected to Western sanctions for carrying out brutal crackdowns on Syrian protesters during the first year of the civil war. His second-in-command, Ghassan Bilal, has reportedly played a key role in this trade as well.

Two months ago, following Syria’s readmission to the Arab League, from which it was suspended 11 years ago, Assad reportedly pledged to clamp down on the production and distribution of Captagon. But it remains to be seen whether he will keep his promise.

In the meantime, profits from the sale of Captagon are filling his coffers with enormous infusions of dollars, propping up his regime, and addicting millions of Arab drug users.