Guy Nattiv’s absorbing feature film, Golda, unfolds during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, but the issues that define it are related to Israel’s current conflict with Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

The Israeli government was surprised by the coordinated offensives launched by Egypt and Syria in the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights on October 6 of that year. Similarly, Israel was caught unaware by the Hamas terrorist rampage in southern Israel on October 6 that resulted in the deaths of 1,400 Israelis and foreigners, the wounding of more than 3,000, and the abduction of some 220 hostages.

In both cases, Israel was colossally unprepared due to intelligence and military failures layered by an abiding sense of hubris. And in both instances, the calls went out for a “humanitarian corridor” to relieve suffering and an immediate ceasefire to end the fighting.

The parallels between 1973 and 2023 are indeed striking, though the two wars are completely different.

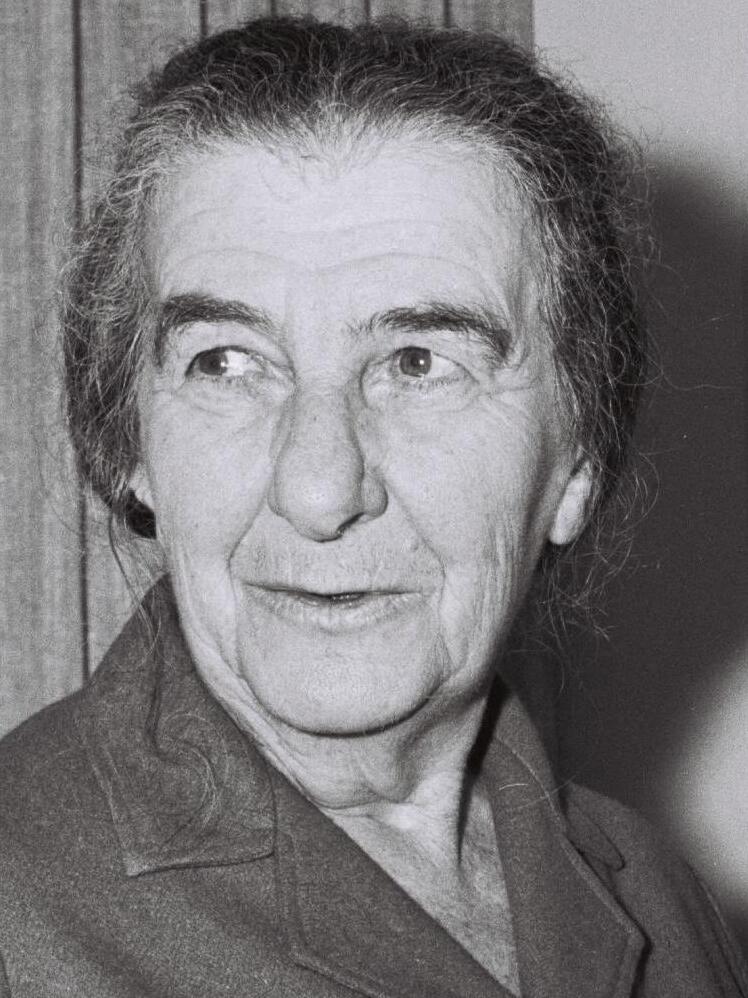

Golda, starring the magnificent Helen Mirren as Prime Minister Golda Meir, starts as she lights a cigarette in the back of a car. She is due to appear before the Agranat Commission of Inquiry, which was established to assess the failures of Israel’s leadership in the prelude to the Yom Kippur War.

“Let’s begin on October 5,” says one of the five members of the commission addressing Meir, who was ultimately responsible for the disaster that befell Israel only a day later.

The Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, got wind of the impending Arab attack on October 5, but Defence Minister Moshe Dayan (Rami Heuberger) was skeptical, thinking that the Egyptians and Syrians were merely conducting more military maneuvers.

The scene shifts to Meir’s office as her faithful personal secretary, Lou Keddar (Camille Cottin), accompanies her to the Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem for cancer treatment.

Back in Tel Aviv, the Israelis learn from their extremely well-informed Egyptian spy in Cairo that war is imminent. Eli Zeira (Dvir Benedek), the director of military intelligence, scoffs at his warning, but General David Elazar (Lior Ashkenazi), the chief of staff of the armed forces, is uneasy and recommends that 200,000 reservists be called up. Dayan thinks he’s exaggerating, but Meir agrees to mobilize 120,000 reservists.

At a subsequent cabinet meeting, Elazar warns Meir that Syria is seriously preparing for war. Meir instructs him to “teach” the Arabs a “lesson” they will never forget. Chiming in, Dayan boasts, “We will crush their bones and tear them from limb to limb.”

These taut and riveting scenes are mixed with black-and-white archival footage of the events leading up to the war. They attest to the blasé mood and arrogance that infected the Israeli government on the eve of the war.

The performances turned in by the actors portraying the main characters are top notch. Mirren, in particular, is outstanding. Decked out in prosthetics and heavy makeup, she almost resembles Meir and, uncannily enough, speaks in a nearly identical accent.

As the tension escalates, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (Liev Schreiber) phones Meir. “We’ve got troubles with the neighbors again,” he says in an understatement. To which Meir replies, “If they (Arabs) want (their) land back, they have to recognize the sovereign state of Israel.”

With Egyptian and Syrian armies advancing into Israel-held territory on both fronts, Meir is informed that the tide is turning against Israel. Frazzled by the setbacks, Dayan says, “We’ve lost the north. It’s Armageddon. This is another Massada. I have failed.”

Meir remains cool and resolute. “I need you on your feet,” she tells Dayan, demanding that he snap out of his depression. But realizing that Dayan is having something of a nervous breakdown, she instructs Elazar to “take over.”

He, in turn, informs Meir that the Egyptian army has succeeded in breaching the Bar-Lev Line along the Suez Canal, and that 600 Israeli reservists are trapped in fortifications there.

Dayan warns Meir that an Israeli counter-attack could be a deadly trap for Israel. “This is 1948 again,” murmurs Meir in a reference to Israel’s first war with the Arab states. “We are fighting for our lives.”

Israel’s counter-offensive in the Sinai is a fiasco. Egyptian Sagger missiles destroy columns of Israel tanks and anti-aircraft batteries shoot down F-4 Phantom jets. This somber news distresses Meir.

With Israel having failed to drive the Egyptians out of the Sinai, General Ariel Sharon (Ohad Knoller) makes an out-of-the-box suggestion. Israeli forces should exploit a small gap in Egypt’s lines and cross the canal into western Egypt. Elazar expresses doubts about Sharon’s audacious plan, but Meir supports him and predicts he will be prime minister one day.

By this point, the Syrians have been pushed back and Kissinger has offered to resupply Israel with a new batch of Phantoms. President Richard Nixon, however, demands an immediate ceasefire.

Dayan urges her to accept a truce, but Meir is adamant, particularly in light of Israel’s most recent success in foiling Egypt’s latest offensive.

Sharon, having crossed into the African continent, faces bitter battles. Seven hundred Israeli soldiers are killed in western Egypt, many at a place known as the “Chinese Farm.” But Israel manages to cut off and surround Egypt’s Third Army of 30,000 troops.

Kissinger, played exceedingly well by Schreiber, arrives in Israel, and Meir serves him borscht. In an instructive scene, he defines himself, in descending order, as an American, the secretary of state and a Jew. “We read from right to left in Israel,” she counters.

Harping on the need for a ceasefire, Kissinger explains that the United States is already paying a high price for its support of Israel, but adds that America will always “protect” it.

Later, Kissinger demands a humanitarian corridor to funnel supplies to the Israeli-besieged Third Army. In return, Meir expects Egypt’s recognition of Israel. Kissinger warns her that the Soviet Union, Egypt’s ally, is preparing to intervene with eleven army divisions.

Much to Meir’s astonishment, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat offers to engage Israel in direct talks.

Circling back to the Agranat Commission’s proceedings, Meir discloses that Israel’s listening devices to detect Egyptian army movements were shut off on October 6. “My gut told me that war was coming, but I ignored it,” she confesses.

Golda fast forwards to Sadat’s historic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977, which led to Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. Meir and Sadat exchange pleasantries and belly laughs. Who could have known that these adversaries would find themselves cheek by jowl so soon after a war that altered the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East.