Exactly a century ago, Germany was on the edge of the precipice, muddling through a year that could easily be classified as annus horribilis. Still struggling from its ignominious defeat in World War I, Germany was reaping its whirlwind.

France and Belgium, having lost patience with Germany’s failure to honor its crushing reparation commitments, invaded the Ruhr Valley, its industrial heartland.

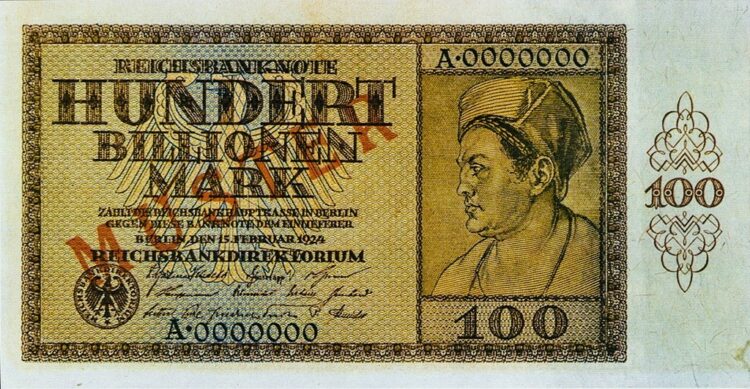

Meanwhile, hyperinflation of a kind unknown to economists wiped out the hard-earned savings of countless Germans, driving them into impoverishment and creating a tide of bitterness that played right into the hands of extreme right-wing politicians eager to dispense with democracy.

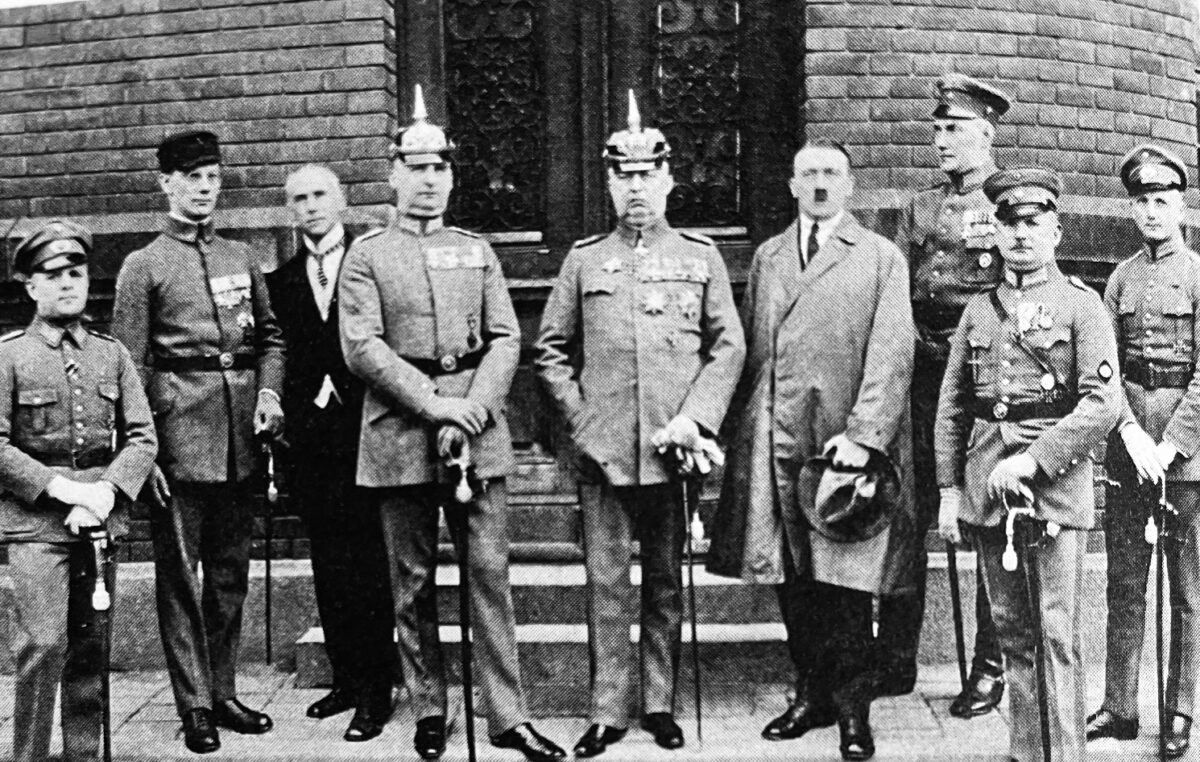

One of its key figures, Adolf Hitler, staged the Beer Hall insurrection in Munich, which was quickly suppressed by the authorities and landed Hitler in prison.

These momentous events, which added up to a perfect political storm, are skillfully recounted by German historian Volker Ullrich in his fascinating and first-rate book, Germany 1923: Hyperinflation, Hitler’s Putsch, and Democracy In Crisis (Liveright Publishing Corporation).

As he aptly puts it on page one, “The year 1923 started with a bang.”

On January 11, French and Belgian troops marched into the Ruhr Valley, the center of Germany’s coal mining, steel and iron industries, after the German government reneged on an agreement under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. They would remain there until August 1925.

On that very day, Hitler, the chairman of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, delivered a fiery speech claiming that the German army had been “stabbed in the back” by criminals and traitors from democrats and Jews on down.

Within two months of the invasion, 75,000 to 100,00 French soldiers and 8,000 Belgian troops had occupied a swath of Germany containing the cities of Dortmund, Gelsenkirchen and Bochum.

Ruling out a military response to the occupation, the German government hewed to what Ullrich calls a policy of “passive resistance.” Nonetheless, 109 people were killed in clashes with the invaders, and saboteurs blew up train tracks and bridges to prevent the transport of coal to France and Belgium.

As Ullrich suggests, the chaos and instability that convulsed Germany in 1923 really began on June 24, 1922, when Walther Rathenau, Germany’s first and still only Jewish foreign minister, was assassinated in Berlin by right-wing radicals. His assassination was proof that fascists were unreconciled to the Weimar Republic, which emerged after the war.

Currency reform was urgently needed after 1918, but, as he notes, post-war governments did not take that step and “prioritized keeping the social peace over reining in the national budget and stabilizing the mark.” As a result, it fell precipitously in value. By the summer of 1923, the exchange rate reached a million marks to the U.S. dollar and a lady’s dress and a man’s trouser sold for 55 million and 6.5 million marks respectively.

While the devalued mark favored exporters, hyperinflation had a catastrophic impact on most Germans, with pensioners, white-collar workers and civil servants being most drastically affected. Property owners holding mortgages, industrialists and foreign tourists benefited.

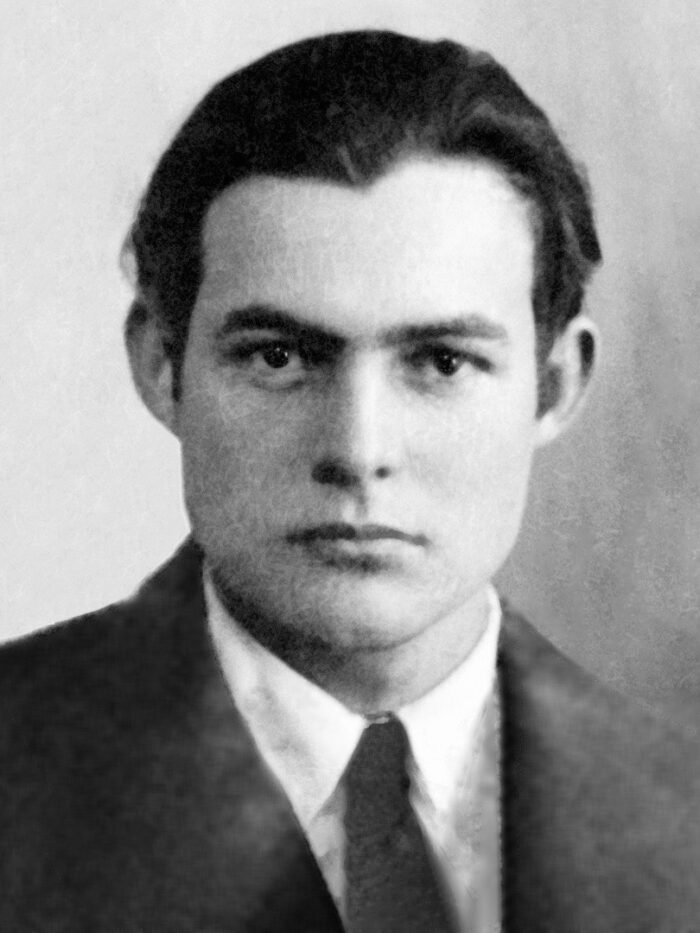

Reporting on the collapse of the mark, the American journalist Ernest Hemingway, a freelancer for the Toronto Star, travelled to a German town near the French border and exchanged the equivalent of 90 Canadian cents for 670 marks. It was enough to last him and his wife an entire day.

In Berlin, an American tourist could live like a king for a dollar a week, while a foreign diplomat could afford a lavish lifestyle.

“The almost complete devaluation of the mark was accompanied by a fundamental suspension of previous norms and values,” Ullrich writes. “Virtues like thrift, honesty and community solidarity were no longer binding, trumped by selfishness, unscrupulousness and cynicism.”

He adds, “The loss of trust in money as a repository of value also robbed Germans of their faith in the existing political and social order.”

Since hyperinflation could not be easily explained, many Germans blamed dark forces and tapped into existing racist resentments. A report on popular sentiments in Bavaria concluded, “The hatred of the broadest circles is increasingly directed against the Jews, who have seized the majority of trade and who, according to prevailing opinion, enrich themselves … at the cost of their fellow human beings.”

In Ullrich’s view, “this was ideal soil for Hitler’s unbridled demagoguery.”

Since the end of the war and the collapse of the Wilhelmine empire in 1918, some Germans, particularly those on the far right of the spectrum, had been calling for a strongman to lift Germany out of its predicament. “While monarchists dreamed of a return to Wilhelmine authoritarianism, racists wanted to create an ethnically homogenous ‘popular community’ under strict dictatorial leadership,” says Ullrich, whose previous book was Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945.

Hitler, who had been a failed artist in Vienna and a lowly corporal during the war, voiced the grievances of disaffected Germans. Speaking in Munich’s beer halls, he railed against the “shameful peace of Versailles” and denounced Jews. Stefan Grossmann, a local publisher, warned his readers in Tage-Buch not to underestimate his talents as an orator.

On November 9, Hitler and his followers staged a coup, and in a melee with police in the center of Munich, 14 of the putschists were killed in a gun battle. He contemplated suicide, but went on a hunger strike instead. With the authorities having banned the Nazi Party, closed its offices, and confiscated its property, The New York Times prophesied that the abortive putsch spelled the end of Hitler’s career.

Hitler and three co-conspirators were given five-year prison sentences with a possibility of parole after only six months. Weimar Republic supporters were shocked by the outcome of the trial, which reinforced Hitler’s belief that he had been charged with a historic mission.

“With the friendly support of a Bavarian court, he had been able to transform his fiasco of a coup into a propaganda triumph,” Ullrich observes. “He and his fellow inmates spent a few quite comfortable months in Landsberg prison, where he typed most of the manuscript for his screed Mein Kampf. If the law had been upheld and justice served, Hitler would have disappeared behind bars for years, and it would have been far harder for him to launch a second political career. As things turned out, he was released … and immediately started rebuilding the Nazi Party.”

Although the Weimar Republic was an incubator for Hitler’s ideas, it was equally a forum for the remarkable efflorescence of German culture.

As Ullrich explains, “Inflation and hyperinflation didn’t constrain artists and writers as much as might have been expected. Indeed, the crisis seemed to stimulate their creativity, with the need to improvise in response to the collapse of the currency fueling experimentation.”

From the outset, Weimar was “a laboratory for modernism,” with literature, theater, art and music finding a broader audience. “New media like film and radio sped the transition to mass culture,” he says.

With its wide assortment of newspapers, cabarets, theaters and movie houses, Berlin became an irresistible magnet for writers, journalists and artists.

The new cultural currents met fierce resistance from conservatives, who clung to traditional conceptions of art and lambasted alternatives as “cultural Bolshevism.”

Once the mark was stabilized and inflation was brought under control, Germany prospered, with the years from 1924 to 1929 being the epitome of the Golden Twenties. Politically, Germany reconciled with western powers such as France and Britain.

During this interregnum, the Nazi Party lost much of its appeal, judging by the results of general elections. But the instability of German politics was such that many Germans lost faith in democracy and grew tired of the Weimar Republic. This trend was accentuated by the stock market crash.

From 1930 onward, Germany was ruled by three ineffective chancellors — Heinrich Bruning, Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher — while the Nazi Party broke through as a mass movement.

Quoting the exiled Jewish writer Stefan Zweig, Ullrich argues that nothing more than hyperinflation infuriated Germans and threw them into the arms of the Nazis. The novelist Thomas Mann agreed: “There is a direct line between the insanity of German inflation and the insanity of the Third Reich.”

Elections between 1930 and 1932 established the Nazi Party as the most powerful political party in Germany, though it never won more than 37 percent of the vote.

Ullrich blames Germany’s geriatric conservative president, Paul von Hindenburg, for having laid the groundwork for Hitler’s accession to power on January 30, 1933. Hindenburg, a creature of the retrogressive forces that despised the Weimar Republic, fervently believed that Hitler could be controlled and harnessed in the service of their narrow interests.

It was a “tragic illusion,” writes Ullrich. “Hitler needed only a few months to overcome all opposition and set up a national dictatorship whose radicalism and inhumanity went drastically beyond anything the enemies of democracy in business, politics and the military could have ever envisioned in 1923.”