Akira Kitade tells two interlocking stories in Emerging Heroes: World War II-Era Diplomats, Jewish Refugees, And Escape To Japan, published by Academic Studies Press.

First, he introduces readers to Tatsuo Osaka, an official in the Japan Tourist Bureau — later known as the Japan National Tourist Organization — who helped Jewish refugees travel from the Soviet Union to Japan, by way of the Sea of Japan, from the end of 1940 to the spring of 1941.

Second, he pays tribute to Japanese, Dutch and Polish diplomats who assisted Jews by various means during this dangerous period.

The most notable figure in this circle, Chiune Sugihara, was the Japanese vice consul in Kaunas, Lithuania, who saved thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews by virtue of his heroic decision to issue more than 2,000 transit visas.

He performed this invaluable service to his own detriment, knowing full well that the Japanese government had tightened visa regulations in the face of pressure from its ally, Nazi Germany. As a result of his humanitarian gesture, Sugihara was eventually dismissed from the diplomatic corps, and at one point, he was reduced to penury.

Kitade, who joined the Japan National Tourist Organization in 1966, clearly admires the late Sugihara, the only Japanese person to be honored as a righteous gentile by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum and research center in Jerusalem. He believes his story needs to be broadened to include like-minded rescuers, and he does so in this book, which, unfortunately, tends to be plodding.

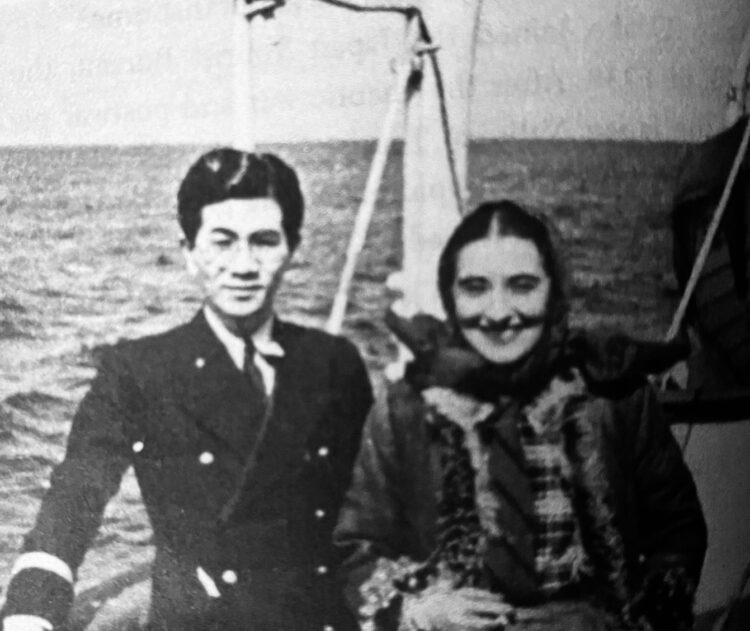

In 1998, Kitade visited Osako, his former boss, after five years of working abroad. Kitade, having learned he had been in charge of transporting Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union to Japan, asked Osako about that fraught period, during which time he accompanied these passengers from Vladivostok to Tsuruga.

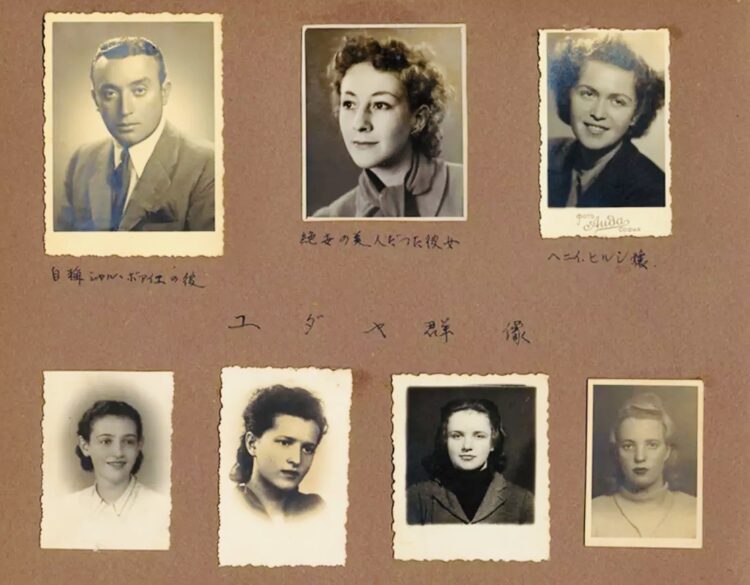

Osako pulled out an old album of photographs from that era. Seven were of people’s faces, one man and six women, all of whom he had taken to Japan.

“Around the first half of 1940, the Japan Tourist Bureau began to support the escape of European Jews to the United States at the request of an American Jewish organization,” Kitade writes without elaborating. “The route was to take the Trans-Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok and go to Tsuruga … on a Japanese ship, the Amakusa Maru. This long journey was the last escape route left for Jewish refugees because most of Europe had been overrun by Nazi Germany.”

The seven photographs had a profound effect on Kitade, who was determined to identify each person after Osako’s death in 2003. Kitade enlisted the aid of three people — Osako’s daughter, a diplomat at the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo, and the director of the Japan Sea Geographical Survey Research Association, which had published a booklet about the refugees.

During the course of his investigation, Kitade visited a few of the refugees and their relatives and descendants. He also identified all but two of the people in the photographs that had so moved him. They included two Jewish women from the Polish city of Lodz and the Polish town of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, a Bulgarian Jewish man, and a Norwegian woman who had tried to join the resistance movement.

To the best of Kitade’s knowledge, Sugihara issued 2,139 visas. Since a single visa was good for an entire family, this meant that Sugihara actually saved upwards of 6,000 Jews.

As Sugihara dispensed visas, Holland’s acting consul in Kaunas, Jan Zwartendijk, a businessman based in Lithuania, issued “Curaçao” visas, which enabled Jewish refugees to travel to Japan and then make the sea voyage to the island of Curaçao, a Dutch colonial possession in the West Indies. He did so with the support of L. P. J. De Decker, the Dutch ambassador in Latvia.

Saburo Nei, Japan’s consul general in Vladivostok, and Yoshitsugu Tatekawa, the Japanese ambassador in the Soviet Union, were also instrumental in helping Jews escape from Europe, according to Kitade, who cites one case in particular.

In the winter of 1941, Rischel Kotler, a Lithuanian Jewish woman, managed to enter Japan’s embassy in Moscow and obtain a visa from the ambassador himself. Nearly three weeks later, she landed in Japan, bound for the Chinese city of Shanghai. From there, she immigrated to the United States via Canada.

Tadeusz Romer, Poland’s ambassador in Japan, played a role in the resettlement of Polish Jews who held visas provided by Sugihara. Under his direction, the Polish Committee for Assistance to War Victims was established in Tokyo and Kobe. It cooperated with Jewish organizations in Yokohama and Kobe.

“Whenever a large group of refugees from Vladivostok arrived in Tsuruga, representatives of the committee went there to meet them, help them with immigration procedures, and assist them in boarding the train to Kobe,” says Kitade.

Romer, the Polish government-in-exile’s foreign minister from 1943 to 1944, immigrated to Canada in 1945 and taught at McGill University. He died in 1978 at the age of 84.

These nearly forgotten footnotes in the annals of the Holocaust are resurrected with passion and conviction by Kitade, who has devoted himself to building bridges of mutual understanding between Japan and Jews. In Emerging Heroes, he salutes the Japanese and foreign diplomats who went above and beyond the call of duty to lend a helpful hand to Jewish refugees during their darkest hours of duress.