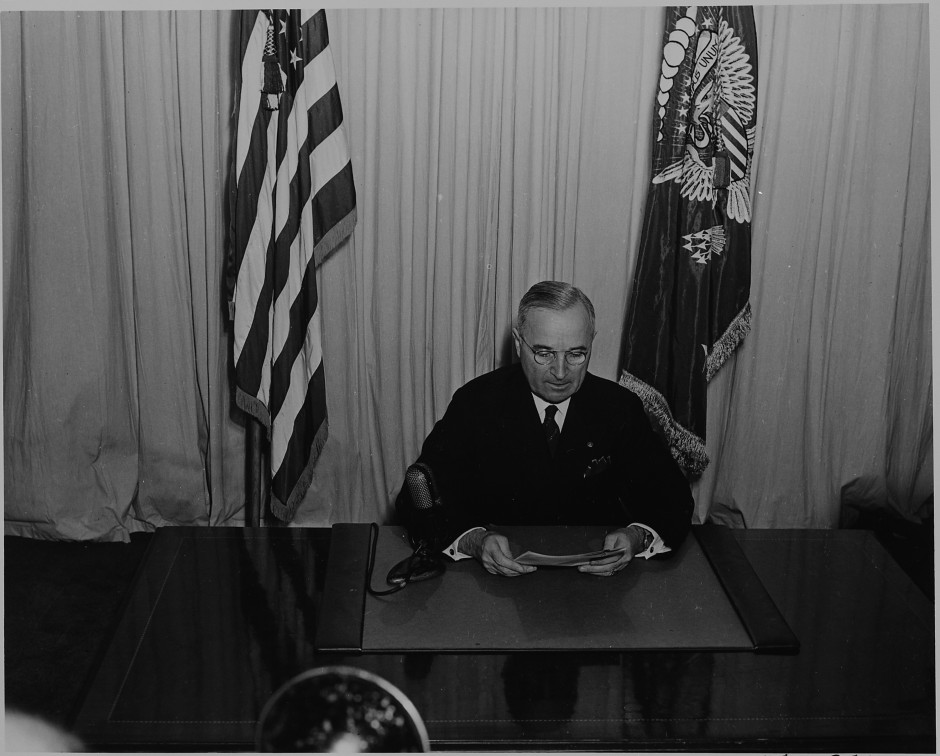

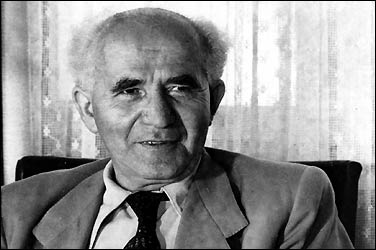

The United States, with Harry Truman as its president, recognized Israel only 11 minutes after its first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, declared statehood on May 14, 1948. And so Truman was immortalized by Zionists as a great supporter of Jewish statehood. But as John Judis points out in Genesis: Truman, American Jews, And The Origins Of The Arab/Israeli Conflict (Farrar, Strauss And Giroux), he was really a reluctant Zionist who was pressured into embracing this solution.

“Far from being a Christian Zionist,” he writes, “Truman was deeply skeptical about the Zionist project of founding a Jewish state, as he repeatedly told Jewish leaders during his first term in office.”

Being a Jeffersonian Democrat who rejected the idea of a state religion, Truman did not believe that a nation should be defined by a particular people, race or religion. Concerned that a pro-Zionist position would jeopardize U.S. interests in the Middle East at a time when the United States and its allies might need Arab oil to fight a war against the Soviet Union, Truman was initially in favor of a federated Jewish-Arab state.

Even after Washington formally accepted Israel’s existence, he notes, Truman urged Israel to return the land that had been allocated to the Arabs under the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan and allow many of the 700,000 displaced Palestinian Arabs to return to their homes.

“Truman was a genuine liberal who had moral qualms about Zionism,” writes Judis, a senior editor at The New Republic. “He was the last president to express them.”

Genesis is an ideologically slanted but substantive book. Readers should be mindful that Judis, a Jew, is an anti-Zionist who would have preferred a far different outcome — a binational or federated Palestine. The Palestinian leadership, of course, fought for a single Arab state in which Jews would have been a tolerated minority. In light of the Holocaust and the religious, historical and linguistic connection of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, it’s understandable why the vast majority of Jews, both in Palestine and the Diaspora, were keen supporters of a Jewish state.

On this pivotal issue, Judis diverges from the Jewish consensus. Arguing that “many different peoples” lived in Palestine throughout the centuries, he writes, “In historical terms, the Zionist claim to Palestine had no more validity than the claim by some radical Islamists to a new caliphate.”

The argument is facile, superficial and even insulting, but hardly surprising. In keeping with his views, Judis admires the cultural Zionist Ahad Ha’am, who called for a spiritual Jewish center, rather than a fullblown state, in Palestine. “He would advocate a country where two nationalities, Jewish and Arab, could live side by side,” he writes, adding that Ahad Ha’am’s vision left “an opening for compromise” with the Palestinian Arabs. But as he admits, most Zionist leaders rejected that option out of hand.

Judis’ survey of the period from the late 19th century to Israel’s birth is concise and informative, but his analysis is colored by a staunch opposition to Zionism per se.

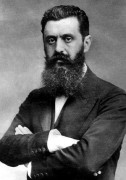

In a reference to Britain’s colonial ambitions in the Middle East, he says that Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, succeeded in accommodating Zionism to “Great Power imperialism.” He asserts that the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain expressed support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, confirmed “the Arab nightmare” that Western forces were trying “to rob Arabs and Muslims of their birthright.” In a further commentary on the Balfour Declaration, he declares that it emboldened political Zionists who insisted on a Jewish state and marginalized cultural Zionists who sought to build a Jewish community in a binational Palestine.

Judis is critical of Chaim Weizmann, a major figure in the Zionist movement, accusing him of having fudged Jewish intentions in Palestine. Weizmann, he says, supported both a “national home” and a “Jewish national home” for Jews in Palestine.

Ben-Gurion and Labor Zionists like him, he observes, were “interested not in reaching an accommodation with the Arabs but in laying the basis for a Jewish state.” That’s only half true, since mainstream Zionists tried in vain to reach a modus vivendi with the intransigent Palestinian leadership.

Turning to the United States, Judis describes Louis Brandeis as the most visible and active figure in American Zionism from 1917 to 1941. Brandeis, a Supreme Court judge, refused to believe Arabs would object to a Jewish state and, like Herzl in Altneuland and Benjamin Netanyahu in recent years, maintained that the answer to the “Arab question” was economic development that would benefit Jews and Arabs alike.

Moving forward to the 1940s, Judis, correctly, reminds readers that Franklin Roosevelt pursued “a contradictory policy” toward Palestine. In 1944, during the presidential election campaign, he voiced support for the establishment of “a free and democratic Jewish commonwealth” in Palestine. But four months later, in a meeting with the king of Saudi Arabia, he promised Ibn Saud that he “would do nothing to assist the Jews against the Arabs …”

As Judis says, Roosevelt’s successor, Truman, had given little thought to the conflict in Palestine. Truman, who had been a U.S. senator before becoming vice-president, was a bundle of contradictions. Like many Americans of his generation, he was prone to casual antisemitism, yet denounced Nazi Germany’s mistreatment of Jews. In 1942, he signed a full page newspaper ad commemorating the Balfour Declaration, but in 1944, he was one of only 17 senators to oppose a resolution in favor of a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine.

After assuming the presidency in 1945, Truman had to maneuver between the increasingly growing Zionist lobby, which has allies in the White House, and the State Department, which opposed Jewish statehood.

Truman backed demands for the resettlement of Holocaust survivors in Palestine, but he was lukewarm on creating a Jewish state, thinking it would be a theocracy. Indeed, he regarded the Morrison-Grady plan for a federated Palestine as the best way out of a morass. “In the end Truman would accede to the Zionists’ pressure — not because he believed in their cause, but because he worried about Democratic losses in 1946 and again in 1948.”

Truman supported the 1947 partition plan, which never came to fruition due to Arab opposition, but by the same token, he imposed an arms embargo on the combatants. By this point, the vast majority of American Jews were Zionists.

The secretary of state, George Marshall, the defence secretary, James Forrestal, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, were all against Jewish statehood. But Clark Clifford, Truman’s speech writer and policy advisor, recommended it. The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Warren Austin, caused an uproar in Zionist circles by calling for a “temporary trusteeship” in Palestine. But his speech was overtaken by events, namely the 1948 War of Independence.

“Truman would later revel in the honors that the Jewish state bestowed upon him, but in the immediate aftermath of recognzing Israel he remained unconvinced of its necessity or its moral wisdom,” Judis claims.

In the aftermath of the 1948 war, the Truman administration tried to convince Israel to adjust its borders and to repatriate the Palestinian refugees, but to no avail. “Truman couldn’t understand how the Israelis could deny the Palestinian Arabs the ‘right of return’ that the Jews had fought for,” Judis says.

Truman had little choice in recognizing Israel, Judis acknowledges. But he might have been influential in the creation of a binational or federated state had he resorted to armed force to impose an agreement on the Jews and the Arabs. “With the Cold War looming, and with the American public tired of war, Truman was not ready to do that.”

In closing, Judis states that Zionists who came to Palestine “trampled on the rights of the Arabs who already lived there.” That’s a questionable thesis, but he’s entitled to it.

Looking ahead, he urges the United States to treat Palestinian national claims justly. They should be, but not at Israel’s expense.