Two words come to mind to describe the rash and unreasonable decision by Guernica to retract a personal essay by Israeli author Joanna Chen: disgusting and disgraceful.

It reminds us all that cancel culture is thriving in America.

This prominent online literary magazine, based in New York City, is reeling after a self-inflicted wound. On March 4, it published Chen’s piece, “From the Edges of a Broken World,” only to remove it some days later after the multiple resignations of its volunteer editorial staff.

Chen’s first-person account about Arab-Jewish coexistence and the ongoing Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip, however, is thankfully still available, thereby enabling a new batch of readers to judge the quality of her essay without preconceived notions.

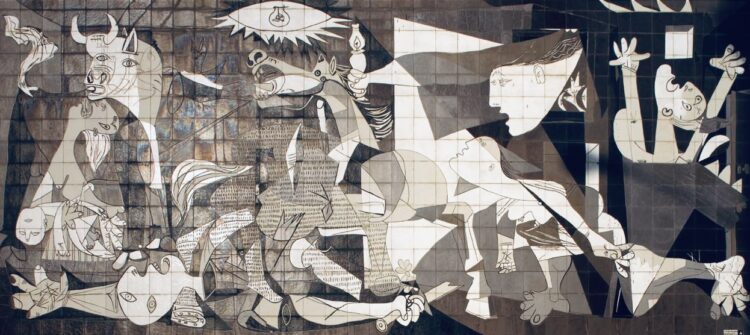

Founded in 2004, Guernica takes its name from Pablo Picasso’s iconic mural, which depicts the 1937 German Air Force bombing of the Basque town of Guernica in northern Spain during the Spanish civil war.

Chen, born in Britain, made aliyah with her family at the age of 16. Today, she lives in the Ella Valley, southeast of Jerusalem. Unlike most Israeli women, she did not serve in the Israeli armed forces. A translator of Hebrew and Arabic poetry and prose, she is an avowed peacenik. Judging by her biography, she values coexistence with her Palestinian Arab neighbors. Chen struck up friendships with Palestinians on the assumption that Jews and Arabs can transcend their political differences and get along on a personal level.

In 2014, during the second Gaza cross-border war, Chen donated blood at a hospital in East Jerusalem, which is populated primarily by Palestinians. She volunteers her services to Road to Recovery, a non-governmental organization whose members drive Palestinian children from the West Bank and Gaza to receive medical treatment at Israeli hospitals.

In her essay, her second one for Guernica, Chen wrote about her past experiences and her efforts to reconnect with a former Palestinian colleague in the wake of the October 7 massacre, during which Hamas terrorists killed roughly 1,200 Israelis and foreigners in a murderous rampage reminiscent of the Holocaust.

Chen worked on her essay with Guernica’s editor-on-chief and publisher, Jina Moore Ngarambe, a former Africa bureau chief of The New York Times.

Within days of its publication, about ten members of the magazine’s staff resigned in protest.

Madhuri Sastry quit as co-publisher after denouncing the essay as “a hand-wringing apologia for Zionism and the ongoing genocide in Palestine.” She called for the resignation of Ngarambe, who has remained conspicuously silent.

Guernica‘s former fiction editor, Ishita Marwa, not only slammed the essay as a “rank piece of genocide apologia,” but lambasted the magazine as a “pillar of eugenicist white colonialism masquerading as goodness.”

April Zhu, who resigned as a senior editor, likened Israel to “a violent, imperialist, colonial power” and claimed the essay had dehumanized the Palestinians.

Responding to the uproar, Guernica replaced it with an editorial note stating its regret at having published it, noting it had been “retracted,” and promising a “further explanation” in the future. This has yet to be published.

Chen, in reacting to the controversy, said her critics had misunderstood the meaning of her essay, which is about “holding on to empathy when there is no human decency in sight. It is about the willingness to listen and the idea that remaining deaf to voices other than your own won’t bring the solution.”

In a statement to the Times of Israel, Chen said, “Removing any stories and silencing any voices is the opposite of progress and the opposite of literature. Today, people are afraid to listen to voices that do not perfectly mirror their own. But ignorance begets hatred. My essay is an opening to a dialogue that I hope will emerge when the shouting dies down.”

It is worth reading the essay, which is thoughtful, compassionate and balanced. Here are a few excerpts:

“For two weeks after October 7, I was unable to focus on my translation work,” she writes in one passage. “It felt disembodied, as if the poems I was working on were floating somewhere above my head, out of reach. They made no sense to me. I spent my time volunteering with an Israeli family from Kfar Aza, bordering the Gaza Strip. Their daughter, son-in-law, and nephew had been murdered. Their house had been torched, and they were evacuated to my village, where they were temporarily living at the end of my street. Neighbors. I mopped their floor, did their dishes, washed their clothes. I heated up plates of food when they were hungry and hugged them when they looked like they needed it. What does a person look like when they need a hug? Like they are lost. It was the least I could do.”

She goes on to say that she temporarily stopped volunteering for Road to Recovery. “How could I continue after Hamas had massacred and kidnapped so many civilians, including Road to Recovery members, such as Vivian Silver, a longtime Canadian peace activist? And I admit, I was afraid for my own life.”

Chen adds, “I phoned friends to find out how they were doing. Some had sons serving in the army in the south; others were struggling to keep going. A neighbor told me she was trying to calm her children, who were frightened by the sound of warplanes flying over the house day and night. I tell them these are good booms. She grimaced, and I understood the subtext, that the Israeli army was bombing Gaza.

“My own heart was in turmoil. It is not easy to tread the line of empathy, to feel passion for both sides. But as the days went by, the shock turned into a dull pain in my heart and a heaviness in my legs. At night, I lay in bed on my back in the dark, listening to rain against the window. I wondered if the Israeli hostages underground, the children and women, had any way of knowing the weather had turned cold, and I thought of the people of Gaza, the children and women, huddled inside tents supplied by the UN or looking for shelter. I stared up at the ceiling and imagined it moving closer and closer toward me. Not falling or collapsing but moving, like an elevator descending into the ground.

“The horrors that had been perpetrated rose to the surface of my consciousness at these times. I listened to interviews with survivors; I watched videos of atrocities committed by Hamas in southern Israel and reports about the rising number of innocent civilians killed in a devastated Gaza.

“There is a limit to which the human soul can stomach atrocities and keep going. On the other hand, turning away from distressing footage taken by Hamas terrorists, by surveillance cameras, and by people running for their lives or sheltering from missiles meant turning away from their pain. I couldn’t do it.”

Chen’s essay, though empathetic to both sides, was clearly unacceptable to her critics because it veered away from the realm of prescribed thinking. In all probability, they objected to Chen’s understandable references to “good booms” and Hamas “atrocities.”

The ideologues who were offended by her essay have chosen sides. They are solidly pro-Palestinian and unabashedly on the side of Hamas. They detest Israel as an abomination. They belong to the “river-to-the-sea” crowd that reflects Hamas’ odious national charter, which calls for Israel’s destruction and opposes a two-state solution.

Israel, to be sure, is a flawed state. But to the protesters at Guernica, this is an irrelevant issue. In their constricted and myopic world, Israel is an illegitimate colonial settler state that has no right to exist, period.

They mistakenly believe that Jews have no claim to the land, even though they are indigenous to Israel and are not remotely like the French settlers of Algeria. Jews have lived in the Land of Israel for centuries, long before the rise of Islam or the formation of Palestinian national consciousness. That Jews were driven out of their homeland, into the Diaspora, by a succession of foreign invaders from the Assyrians to the Romans has no bearing on their skewed thinking.

As Chen suggested, these are stifling conformists/totalitarians who cannot tolerate an idea that goes against the grain of their one-dimensional group thinking. They resemble the Maoists of China during the Cultural Revolution, the Stalinists of the Soviet Union during its darkest period, the fascists of Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, and the mullahs of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

They are the thought police of George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984, the Big Brothers who have taken woke creed to a disturbing level.

If Guernica has any self-respect, it will republish Chen’s essay, issue a sincere apology, and hire a roster of new editors whose heads are not buried in the sand.

Guernica should be true to the uncompromising proposition that openness, flexibility, honesty and integrity are not alien intellectual concepts, particularly in a magazine that, in its mission statement, strives to address “incisive ideas and necessary questions.”

This means that Guernica should be receptive to different points of view and that it should embark on a new era unencumbered by the sycophantic baggage of the past.