Tony Bernard’s thoughtful and absorbing book, The Ghost Tattoo (Citadel Press), is dedicated to his late father, Henry Bierzynski Bernard, a Polish survivor of the Holocaust who was traumatized by it.

At the very least, his memoir is intensely personal. As he writes, “It is also a part of my long journey to get closer to him, to find out what troubled him and to help him to achieve the true and deep peace of mind that eluded him to the last.”

Although Henry achieved success as a family doctor in postwar Sydney, Australia, his wartime experiences left a legacy of sadness and melancholy that led to obsessive behavior and prompted his second wife, Evelyn, to leave and divorce him.

In a compensation claim to West Germany, he stated that he suffered from claustrophobia, nightmares, insomnia, tension headaches, nervous stomach pains, heartburn and back pain.

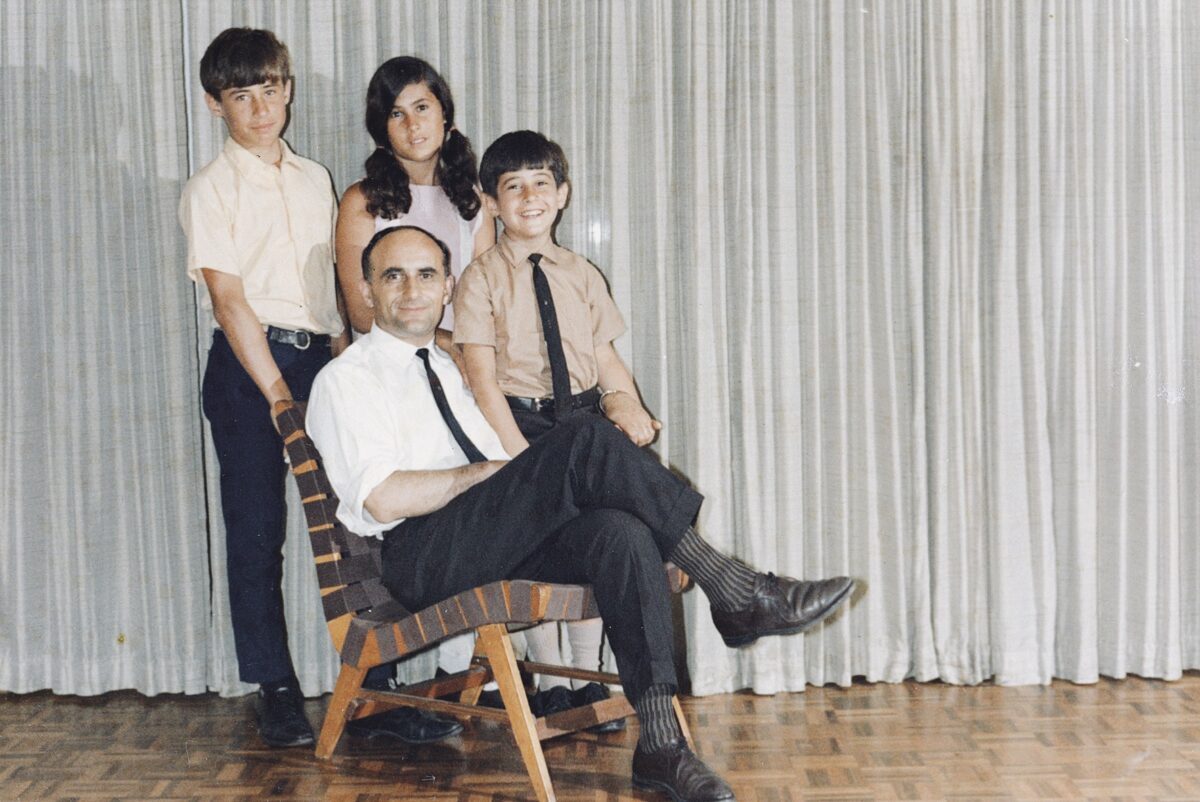

Tony, his eldest child and a physician himself, was vaguely aware of his ordeal under the Nazis. But he and his two siblings did not know what lay behind behind the tattoo that was burned into his arm in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. He refers to this tattoo as the “ghost tattoo” that only Henry “could see and feel.”

Tony’s relationship with Henry was complicated: “He was so close to me, and yet he was also an enigma.”

Unlike most Holocaust survivors, Henry distanced himself from his Jewish identity, which had caused him so much anguish. “We never celebrated a single Jewish holiday. We never went to a synagogue. We did not participate in any Jewish community events and had no real idea that we were Jewish … Henry would do everything he could to protect us from being identified as Jewish.” But as Tony notes, Henry’s attempt to bury his Jewish past did not bring him inner peace.

Henry was born in 1920 in Tomaszow Mazowiecki, a town of 40,000 southwest of Warsaw whose population was composed of Catholic Poles, ethnic Germans and Jews, with a sprinkling of Orthodox Russians.

His secular and assimilated family considered themselves Polish patriots, spoke only Polish at home and did not speak Yiddish. In terms of their appearance, they could have passed for Polish Catholics. Due to his physiognomy, he was not particularly affected by antisemitism. But Jews who looked Jewish were sometimes persecuted and pushed around. “There was an undercurrent of resentment, always lurking below the surface, in some of the Polish Catholic population.”

During the late 1930s, Jewish shopkeepers were subjected to an unofficial economic boycott. And Jews like Henry who aspired to study at university bumped into a restrictive numerus clauses, or Jewish quota system. Henry wanted to study medicine at Warsaw University and met all the academic requirements, but he was rejected, leading his parents to send him to the University of Montpellier in France.

Henry returned to Poland in July 1939 for the summer holiday. Less than two months later, Germany invaded Poland. It was an event that would have a deadly impact on Poland’s 3.3 million Jews.

Within a month of marching into Tomaszow, the Germans destroyed its synagogues. Henry and his first wife, Halina, hatched a plan to escape to eastern Poland, which was occupied by the Red Army under the 1939 Soviet-German non-aggression pact. But having heard that starvation was the norm there, they remained in Tomaszow.

At his father’s request, Henry joined the Jewish Order Service, the Jewish ghetto police, in 1940. It was a job he would regret for the rest of his life. “It was only late in life that he decided to speak about the role he played as a ghetto policeman … I never fully appreciated the depth of Henry’s shame and regret about his role in the ghetto police during his lifetime.”

Henry claims he acted as “honorably as he could under the circumstances.” But he understood that the Nazi-appointed Jewish Council and the ghetto police unknowingly assisted the Nazis in their diabolical plan to murder the Jews of Tomaszow. To his eternal shame, he could not protect his mother from being deported to a concentration camp.

In May 1943, following the liquidation of the ghetto, they were taken to Blizyn, a labor camp where conditions were appalling. Later, he was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he cleaned toilets. Then he was dispatched to Kaufering, one of Dachau’s subcamps.

American troops liberated Henry in April 1945. He resumed his medical studies in Poland at the University of Wroclaw, but soon realized that “people with a Jewish background would never be accepted into post-war Poland.”

For Henry, the last straw was the 1946 pogrom in Kielce. This is when he decided to immigrate to Australia as soon as possible. He chose Australia because he had an uncle there and wanted to live in a country very far from Poland.

Henry visited Poland regularly, and on four occasions Tony accompanied him. Henry’s visits were not sentimental journeys, but “descents into silence, misery and profound unresolved grief.” He was always happy to return to his home in Sydney.

Tony says that Tomaszow has forgotten its Jewish dimension. “When you visit today there is no sign whatsoever that one-third of the town had been Jewish … The only reminder of Tomaszow’s Jewish past is in the derelict and abandoned Jewish cemetery that sits next to the very neat and still-used Polish cemetery.”

During his final years, Henry was more preoccupied with his wartime experiences than ever before. In his late eighties and early nineties, he was shaken by nightmares witnessed by his girlfriend. He died in 2016, two months short of his 96th birthday.

In closing, Tony writes, “My father experienced the full spectrum of the Holocaust. He was a ghetto policeman … He was an imprisoned worker in the Nazi labor camp at Blizyn, where he tried to kill himself … He spent three months at Auschwitz, where he was tattooed … And finally, he spent the last six months of the war as a slave laborer … before being liberated by the U.S. army.”

And in 1970, he was one of the few survivors who was called as a witness in a war crimes trial in West Germany. “He became that rarest of birds: a Holocaust survivor who manages to convict a Nazi murderer of his crimes.”

The villain in question, a Nazi functionary who was instrumental in causing the deaths of Jews in his hometown in Poland, paid a price for his crimes. But the damage had been done.