Amid a landscape of despair and death, Bulgaria was seen as a shining example of humanity during the Holocaust. Alone among European countries that were occupied by or aligned with Germany, Bulgaria saved its Jewish citizens from the clutch of the Nazis. Its wily monarch, King Boris III, was supposedly their chief protector and savior.

Like the majority of Bulgarian Jews, my late parents-in-law bought into this appealing story. For decades after World War II, Bulgaria burnished these self-serving myths.

While it is true that the 49,000 Jews of Bulgaria survived the war, the pro-German Bulgarian government was anything but philosemitic, writes Jacky Comforty in his illuminating book of essays, The Stolen Narrative of the Bulgarian Jews and the Holocaust (Rowman & Littlefield).

In fact, as he points out in his deeply researched and clearly written account, the Bulgarian fascist regime can justly be accused of ethnic cleansing.

It subjected its Jewish population to horrendous antisemitic restrictions, made plans to deport a significant number of Jews to Nazi concentration camps, and facilitated the mass murder of almost 12,000 Jews in the Bulgarian-occupied areas of Thrace and Macedonia and the city of Pirot.

Comforty, the son of Bulgarian Jews, was born in Israel in 1954 and raised in Tel Aviv. Having explored the history of this community, he interviewed 150 people who represented a spectrum of experiences in Bulgaria before, during and after the Holocaust.

These first-hand accounts underscore Bulgaria’s mistreatment of its Jewish citizens during the war and prove its collaboration with Germany in the Final Solution.

In his useful introduction, Comforty sets out the unpleasant truth.

From the mid-1930s onward, King Boris III incrementally turned Bulgaria into a satellite state of Germany. Nazi ideology and propaganda exacerbated existing antisemitism in the country. A pro-German youth organization, Branik, emerged. And fascist para-militaristic groups, such as Ratnik and the Legioners, flourished. Two of Ratnik’s leaders, Peter Grabovski and Alexander Belev, would be the masterminds of the Holocaust in Bulgaria.

In January 1941, King Boris III signed the Law for the Defence of the Nation, which resembled the anti-Jewish Nuremberg laws of Germany. Shortly afterward, Bulgaria joined the Tripartite Pact, the primary members of which were Germany, Italy and Japan.

Within hours of this event, German troops crossed into Bulgaria, from which they invaded Greece and Yugoslavia. In return for its cooperation, Bulgaria acquired Thrace and Macedonia, which it had lost in the 1912-1913 Balkan wars and World War I. Jews, Greeks and Serbs in the newly annexed territories were exploited and abused by Bulgaria, says Comforty.

On March 3, 1943, the Bulgarian authorities agreed to deport 20,000 Jews, of whom 8,500 were citizens of Bulgaria. Bulgaria’s Jewish leaders managed to convince several prominent politicians, including the vice-president of parliament, and the leadership of the Orthodox Church, to delay the deportations. However, the 11,343 Jews of Thrace and Macedonia were sent to their deaths in Treblinka.

In short order, Jews in Sofia, the capital, were ordered out of the city and resettled in ghettos in other cities as a first step toward deportation. This plan aroused an outcry from certain quarters and was postponed, delayed and finally stopped following the untimely death of King Boris III in August 1943. After his passing, Bulgaria never again tried to deport Jews. In 1944, the nightmare ended when Bulgaria was liberated by the Red Army.

For years, Bulgaria denied responsibility for its complicity in the murder of Jews. What this meant, in practice, was that the Jewish narrative was “hijacked, tainted and silenced” by a well-funded Bulgarian government public relations campaign, he argues convincingly. In 2008, however, the Bulgarian president acknowledged Bulgaria’s role while visiting Israel.

These are complex matters that can only be fully understood within the context of Bulgarian history. Comforty competently places the events of the early 1940s in their proper perspective, but his book is somewhat disjointed and repetitive in terms of style and structure.

Bulgaria, long an Ottoman province, gained its independence in 1878 under the Treaty of Berlin. Its constitution guaranteed equal rights for all its inhabitants. Jewish participation in the Balkans wars and World War I strengthened the relationship between Jews and Christians. Yet antisemitism was ingrained in Bulgarian society. For example, Jews could not become officers in the armed forces. Yet Jewish-Christian friendships were not uncommon.

Although Jews were Bulgarian patriots, they gravitated toward Zionism. When the founder of the Zionist movement, Theodor Herzl, visited Sofia, he was greeted enthusiastically.

King Boris III was no Jew lover. “The great damage to humanity throughout the generations is caused by the Jewish spirit of profiteering,” he wrote in 1943.

This was not an aberration. In 1939, the Bulgarian government expelled 4,000 Jewish “non-residents,” many of whom were born in Bulgaria. A year later, the king appointed an antisemitic Germanophile, Bogdan Filov, as prime minister. He, in turn, selected Gabrovski as minister for internal affairs. Belev, whom Comforty describes as a “pro-Nazi thug,” worked under Gabrovski as a lawyer and was later promoted to head up the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs. They were both instrumental in conceiving and implementing the Law for the Defence of the Nation, which marginalized, stigmatized and persecuted Jews.

From that point onward, Jewish men between the ages of 20 to 40 were drafted into forced labor camps in northern Bulgarian and all Jews were required to wear a dreaded yellow star. In addition, Jews could no longer own and manage businesses and were compelled to change Bulgarian-sounding surnames to Jewish surnames.

The march toward genocide accelerated in 1942, when the Bulgarian Foreign Ministry dispatched a formal note to the German legation in Sofia agreeing to the deportation of Jews. Theodor Dannecker, an SS officer who had orchestrated the roundup of 13,000 Jews in Paris, arrived in Sofia to expedite the process, which was to take place in three phases.

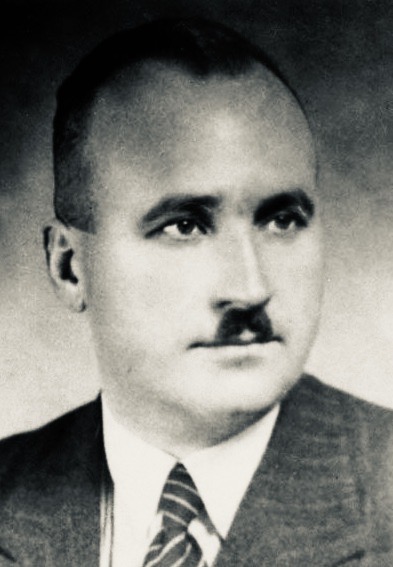

Dimiter Peshev, the vice-president of the Bulgarian National Assembly, attempted to cancel the order. Forty three parliamentarians, representing one-third of the majority party’s members, signed his petition. Under pressure from the king and the prime minister, they withdrew their signatures and Peshev was voted out of office.

Opposition from the Bulgarian Orthodox church and segments of Bulgarian society forced the authorities to abandon the plan to deport Bulgarian Jewish citizens.

In Comforty’s judgment, “Bulgaria, as a country under King Boris III, actively and voluntarily” participated in the Holocaust.” He adds, “His government would have completed the annihilation of the entire Jewish population if not for the looming German defeat and Bulgaria’s growing concerns of the postwar consequences.”

War criminals in postwar communist Bulgaria were duly punished and antisemitism was officially classified as a crime. Nonetheless, most Jews immigrated to Israel, mainly settling in Jaffa, which had been largely populated by Palestinian Arabs before the birth of Israel. My parents-in-law, Moritz and Renee Lazarov, were among the newcomers.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Bulgarian state media lauded the nation’s leader, Todor Zhivkov, for saving Jews. While he and other communists had opposed Bulgaria’s antisemitic policies, they did not “contribute specifically” to stopping the deportations, says Comforty.

The attempt to make him and the king into heroic figures “came at the expense of those deported to Treblinka and those real courageous people who stood up” in defence of Jews, he goes on to say. In a damning indictment, Comforty charges that “the king and his regime voluntarily collaborated in genocide and ethnic cleansing.”

Thirty years ago, memorial stones dedicated to the king and his wife were placed in the Bulgarian Forest in Israel. But with protests emanating from the relatives of Greek and Macedonian Jews who had been deported from Thrace and Macedonia, the stones were removed and installed next to St. Sophia Church in Sofia, where they stand to this day.

Clearly, the Bulgarian government did not acquit itself nobly during the period under review. To his credit, Comforty debunks the myths related to the Holocaust in Bulgaria. No longer can Bulgaria smugly claim that it was a safe haven for Jews during this incredibly dark period.