A little more than a year ago, Yaroslav Hunka, a 98-year-old war veteran of Ukrainian extraction, received two standing ovations in the House of Commons after its Speaker, Anthony Rota, singled him out for recognition. The visiting president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, and the prime minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, were among those who honored Hunka with rounds of applause.

Little did they know that Hunka had been a soldier in the SS Galicia Division, a unit of the German army formed in the final years of World War II. Once the embarrassing blunder was exposed, Rota resigned, Parliament unanimously adopted a resolution condemning Nazism and withdrawing its recognition of Hunka, and Trudeau issued an apology.

Russia exploited the incident to justify its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which it implausibly described as a “special military operation” designed to “denazify” its neighbor.

As Canadian journalist Peter McFarlane suggests in a new book, Canadians should not have been surprised by the Hunka affair. Canada, the first Western nation to formally recognize Ukrainian independence in 1991, has a record of tolerating Nazis. Canada, after 1945, welcomed Ukrainian Nazi collaborators as immigrants.

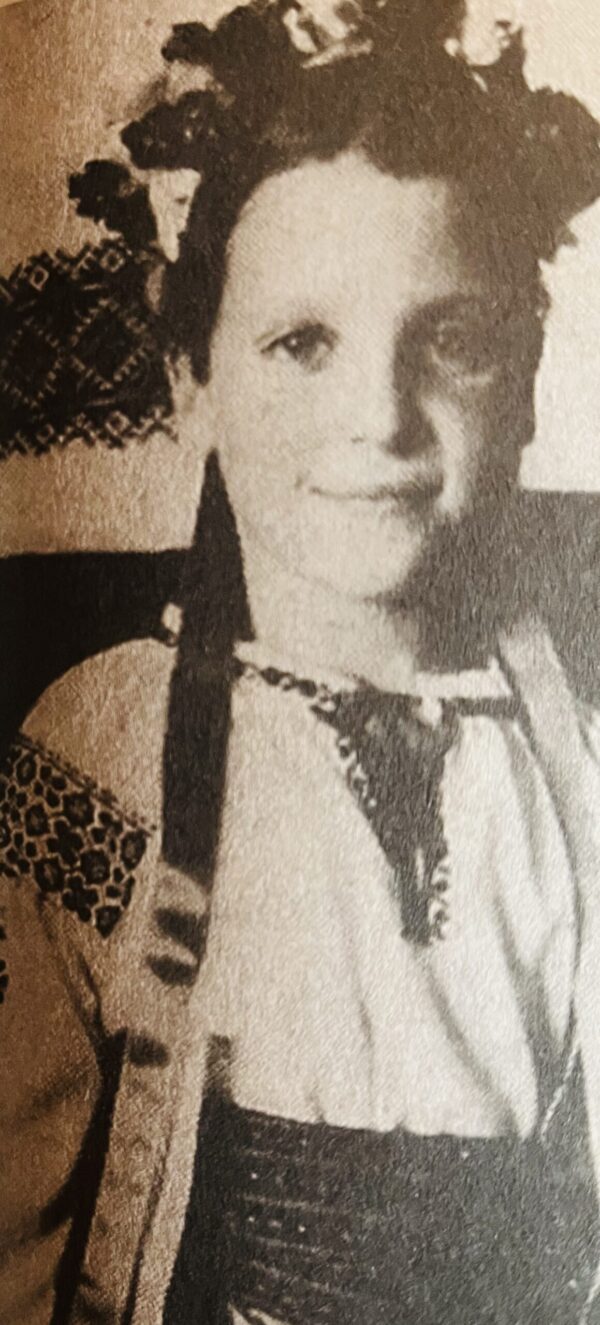

Thousands of them, like Hunka, served as foot soldiers in the German army. Still others, such as Mykhailo Chomiak, the grandfather of Canadian Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, edited a Nazi-financed antisemitic newspaper in German-occupied Poland.

Hunka and Chomiak worked for the Germans in the expectation that Adolf Hitler’s genocidal regime would recognize Ukraine, a province of the Soviet Union, as a sovereign state.

McFarlane explores this facet of Canada’s immigration policy and examines the connections between far-right Ukrainian nationalist organizations and Nazi Germany in his dense and engrossing book, Family Ties: How A Ukrainian Nazi And A Living Witness Link Canada To Ukraine Today (James Lorimer & Company Ltd.)

McFarlane, who often writes from a personal perspective, packs a lot of information into his book, sometimes too much, but it flows smoothly and usually engages a reader.

The “Nazi” and the “living witness” to whom he refers never knew each other. Chomiak was the editor of the Krakow based Krakivski Visti, which was launched in 1940 with German encouragement and funding. Ann Charney, a Jewish Canadian journalist from the Ukrainian city of Brody and McFarlane’s friend, spent years in hiding during the Holocaust.

In addition to contrasting their respective lives, McFarlane introduces readers to the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which was involved in the mass murder of Poles and Jews. He also provides readers with a cogent overview of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). Founded in 1929, it split into rival factions, OUN-B and OUN-M, in 1941 under the respective leadership of Stepan Bandera and Andriy Melnyk, who have been accused of war crimes.

From its inception, OUN embraced fascism and formed close ties with Nazi Germany and Benito Mussolini’s Italy. OUN-B, in particular, was virulently antisemitic, claiming that Jews were in “the vanguard of Muscovite imperialism in Ukraine.”

Yaroslav Stetsko, Bandera’s associate and the prime minister-in-waiting of the Ukrainian state he proclaimed in Lviv on June 30, 1941, branded Jews as “parasites” and “swindlers” and endorsed the Nazi extermination of Jews.

Melnyk, as McFarlane notes, was instrumental in the formation of the SS Galicia Division. In April 1943, Chomiak’s newspaper proclaimed the launch of the division in a front-page story and urged Ukrainian males in Galicia — a region spilling into Ukraine and Poland — to join and fight its “most dangerous enemy, Moscow-Jewish Bolshevism.”

By 1944, the division was battle ready. It was assigned to defend the Brody area, where Ann Charney, her mother, aunt and cousin found refuge in the barn of a Polish farmer who received payment for sustaining them. Much later, while living in Canada, she wrote Dobryd, a searing account of her experiences during the war.

Brody, where Jews once constituted 80 percent of its population, was occupied by Germany in the summer of 1941. In short order, Jews were subjected to a whole range of restrictions and massacres.

Chomiak was born in a village near Lviv, which is relatively close to Brody. After studying law, he edited a newspaper in western Ukraine. He left Lviv when Soviet forces occupied it in September 1939. While a number of Ukrainians welcomed the Soviets, right-wing Ukrainians such as Chomiak fled westward toward Krakow, from which Polish forces had withdrawn voluntarily.

He joined the staff of Krakivski Visti as deputy editor and was soon selected as editor. Its offices and presses had been confiscated from Mojzesz Kanfer, a Jewish publisher who had escaped from Krakow.

“There is no indication in his papers, or in recorded conversations with his family and friends, that Chomiak took any interest in the genocide that was being prosecuted all around him,” writes McFarlane.

Chomiak’s son-in-law, John-Paul Himka, a University of Alberta historian, wrote that it would have been impossible not to have witnessed the brutal treatment of Jews in Krakow. In McFarlane’s estimation, Chomiak very much shared the antisemitic views expressed in Krakivski Visti.

Following the lead of the German governor of Galicia, Chomiak and his family fled Krakow in the autumn of 1944, bound for Vienna. He continued to edit Krakivski Visti until the final days of the war.

After Germany’s unconditional surrender, Chomiak lived in a U.S.-run displaced persons camp in the German town of Bad Worishofen, where Chrystia Freeeland’s mother, Halyna, was born.

Chomiak, his wife and four daughters left Europe by ship in 1948. He registered for the voyage as a bookkeeper. They settled in Cherhill, a small farming community in Alberta where Chomiak’s sister lived. Subsequently, they moved to Edmonton, whose Ukrainian community is well-established.

The first wave of Ukrainian immigrants arrived in Canada in the 1890s. Almost all of them hailed from the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia. The downfall of the Western Ukraine Republic in 1921 led to the second wave. The next one occurred after World War II.

During this period, Canada admitted 2,000 members of the SS Galicia Division. “Jewish groups and progressive Ukrainians denounced the influx … but their voices were quickly drowned out by the Canadian political leadership and their echo chambers in the Canadian media who were quickly refining the Nazi collaborators as Cold War assets,” says McFarlane.

Chomiak immersed himself in Edmonton’s Ukrainian community, especially in institutions linked to OUN. As well, he contributed to what McFarlane calls the “Holocaust revisionist” Ukrainian encyclopedia and played a role in the construction of a 20-foot high monument in a Ukrainian cemetery paying homage to the SS Galicia Division. A similar monument was erected in Oakville, Ontario.

Above all, Chomiak kept the “faith” alive in his family. In other words, he demanded that his children and grandchildren should be faithful to Ukrainian Catholicism, extreme ethno-nationalism, and the imperative of speaking Ukrainian at home.

Halyna, one of his granddaughters, married an ethnic Scottish farmer and lawyer named Donald Freeland. They lived in Peace River, Alberta, where Chrystia Freeland was born in 1968.

Extremely attached to Chomiak, she was schooled in Ukrainian culture and language from an early age. Her approach to Ukrainian nationalism favored the OUN perspective. She joined a youth group where, as McFarlane points out, “Nazi collaborators and Holocaust perpetrators were hailed as national heroes.” And like her grandfather, she chose journalism as a career.

In 2013, she entered politics when the Liberal Party chose her as its candidate in a by-election in the riding of Toronto-Centre. Within two years of her victory, she was appointed a government minister. Prior to her most recent appointments, she was foreign minister.

As a politician, she has accentuated her Ukrainian immigrant background and brushed aside her grandfather’s job as a Nazi propagandist, even in the face of newspaper stories confirming this unpalatable fact and John-Paul Himka’s disclosure that she reviewed his monograph, Krakivski Visti and the Jews, 1943, before its publication in an academic journal in 1996.

Of course, Freeland could not be held responsible for Chomiak’s sins. But when the media seized on the story, “she would not admit the facts” and curtly dismissed them as Russian disinformation, says McFarlane. Furthermore, he adds, she has had links to “extreme nationalist” groups in Canada and Ukraine.

Charney told McFarlane that Freeland had no choice but to stick to her twisted narrative. As he puts it, “Freeland adopted the wilful blindness that infected the postwar Ukrainians from Galicia. To admit that her beloved grandfather was a Nazi collaborator, and quite possibly guilty of advocating and promoting genocide, would put in question her entire world.”

Like Chomiak, Charney and her mother left Ukraine in the wake of the war. They did not want to return to Brody, nearly all of whose Jewish inhabitants were murdered by the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators. In 1951, they immigrated to Canada, settling in Montreal.

Charney studied literature at McGill University and completed her thesis in Paris on Marcel Proust. Having finished her studies, she embarked on a career in journalism, working for, among other publications, Maclean’s magazine as its Quebec correspondent.

In researching this book, McFarlane visited the Brody Museum of History and Local Lore. Much to his surprise, he discovered that there was no mention of Jews and that a large part of a wall in one of its rooms was dominated by photographs of soldiers in the SS Galicia Division.

“So that was it. The Jewish community, which had founded the city and turned it into a bustling trading town and had been murdered here by the thousands by the Germans and by the Ukrainian nationalist militias and auxiliary police, had been formally and officially removed from the history of the town.”

McFarlane describes modern Brody as a “rundown provincial town inhabited by people who long ago gave up hoping for something better in a country mired in war and corruption. The vibrant trading town with several theaters, movie houses and busy cafes had disappeared with the Jewish community.”

He also reports that the highway leading to Brody is a “memory lane” to the SS Galicia Division. Monuments commemorating it were erected in 1990 and 2008 by the Brody District Council.

After his visit to the museum, McFarlane went to Brody’s old Jewish cemetery. When he told his Ukrainian guide that Brody had once been a majority Jewish city, she disputed his information and asked what he thought of Jews. After he answered, he posed the same question to her. “Our president is Jewish,” she replied, referring to Zelensky, who was elected in 2019. “Jews are fine as there aren’t too many of them. Once they move in, they take control of everything. But one or two are fine.”

In closing, McFarlane suggests that two distinctly different forces have been driving Ukrainian politics for at least the past decade. Generally, Ukrainians in the east want to remain in the Russian orbit, while Ukrainians in the west turn toward western Europe and are committed to a brand of fierce ethnic nationalism.

He infers that some western Ukrainians agree with ideas espoused by OUN. Judging by his observations, Ukraine is still wrestling with the ghosts of the past.