Israeli troops remain on the ground in southern Lebanon, despite a ceasefire agreement that required Israel to withdraw from all Lebanese territory following its recent war with Hezbollah.

Israel pulled out of Lebanese towns and villages on February 18, two weeks after it was supposed to do so under a two-month truce that began on November 27, 2024, but there is still an Israeli military presence in Lebanon.

The agreement, brokered by the United States and France, also stipulated that Hezbollah fighters and weapons must be removed from southern Lebanon from points beneath the Litani River, and that the Lebanese army, along with the United Nations peacekeeping force (UNIFIL), must fill the vacuum.

This, so far, has not happened.

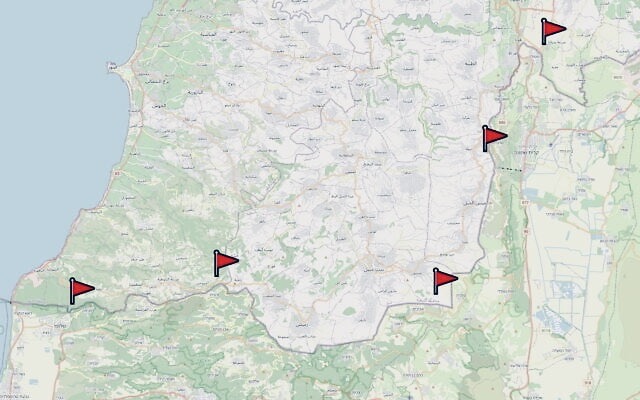

Israel, having accused Hezbollah and Lebanon’s army of failing to uphold the truce, announced it would station troops in five strategic locations along the Lebanese side of its northern border.

The vantage posts overlook the Israeli communities of Shlomi, Zarit, Nurit, Shtula, Avivim, Malkiya, Saluq, Margaliot and Metula. These communities, along with others in the vicinity, were evacuated shortly after Hezbollah started bombarding the Galilee on October 8, 2023. This occurred a day after Hamas terrorists killed roughly 1,200 people and kidnapped 251 Israelis and foreigners in the western Negev.

Hezbollah initiated hostilities in a show of solidarity with Hamas, announcing it would agree to a ceasefire only after the fighting in the Gaza Strip had stopped. Nearly a year later, Hezbollah modified its policy, signing on to a truce even as the war in Gaza raged.

In the face of Hezbollah’s unprovoked aggression, Israel moved some 60,000 Israelis from their homes near the Lebanese frontier. The Israeli government took this drastic step as a precaution, fearing that Hezbollah might launch an invasion of the Galilee and slaughter Israeli civilians. At the same time, Israel rushed reinforcements to the border, deterring Hezbollah from launching an attack on the scale of October 7.

The buffer zone Israel has established in the south of Lebanon is a “temporary measure” designed to protect Israeli border communities “until the Lebanese armed forces are able to fully implement the understandings” of the ceasefire, Israeli military spokesman Nadav Shoshani said a few days ago. “We need to remain at those points at the moment to defend Israeli citizens, to make sure this process is complete and eventually hand it over to the Lebanese armed forces,” he added.

His comments were in line with previous Israeli statements concerning the northern border.

Last week, Israeli Strategic Affairs Minister Ron Dermer said, “We will not allow Hezbollah to rearm and to pose a threat on Israeli civilians again.”

Last November, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned that Israel would maintain “full military freedom of action” in case of any truce breach.

In this connection, the Israeli Air Force has periodically bombed Hezbollah and Hamas sites in Lebanon since the ceasefire. Most recently, an Israeli drone struck a car in the port of Sidon, killing a Hamas official who headed its operations department in Lebanon.

Israel’s five posts appear to be part of a wider Israeli plan to indefinitely hold buffer zones in Lebanon, Syria and the Gaza Strip in the wake of wars in Lebanon and Gaza and the overthrow of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Israel’s decision to maintain extraterritorial outposts has raised fears in Beirut of another prolonged Israeli occupation. Israel occupied swaths of Lebanon after its 1978 and 1982 invasions.

The United Nations maintains that the presence of Israeli troops in Lebanon violates a UN resolution that ended the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah.

The Lebanese government has denounced Israel’s move, saying it will seek the UN Security Council’s assistance to “address Israeli violations and compel Israel to immediately withdraw.” President Joseph Aoun, Prime Minister Nawaf Salam and parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri contend that the Lebanese army is ready “to assume all its duties along the … borders.”

Their claim is disputed by Israel, which states that Hezbollah and the Lebanese army have failed to honor the agreement in its entirety.

As Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz said recently, “The first condition for the implementation of the agreement is the complete withdrawal of the Hezbollah terror organization beyond the Litani River, the dismantling of all weapons, and the removal of the terror infrastructure in the area by the Lebanese army, something that hasn’t happened yet.”

Lebanon’s army begs to differ, saying it can replace Hezbollah only after a full Israeli withdrawal.

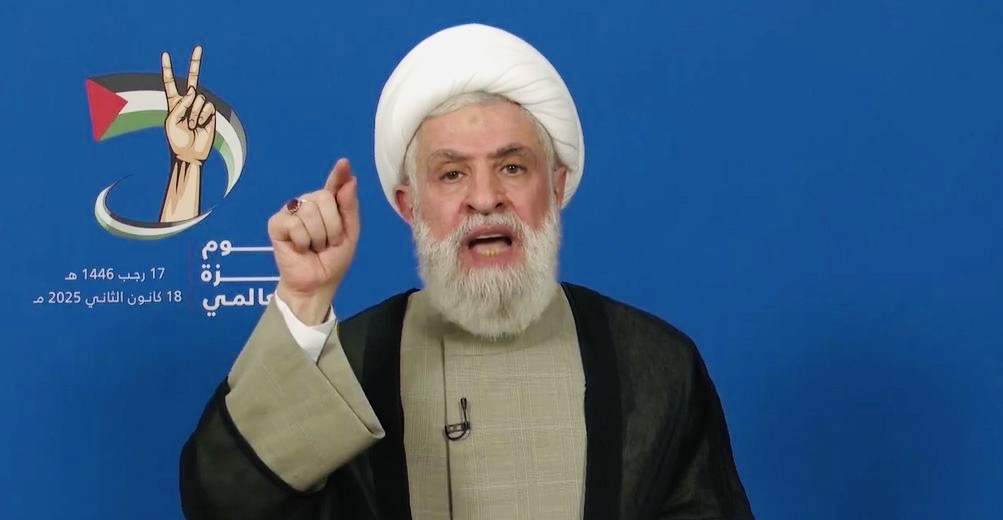

Hezbollah’s leader, Naim Qassem, has demanded a total Israeli pullout. “Everyone knows how an occupation is dealt with,” he warned, implying that Hezbollah can renew the war.

However this problem is resolved, the ceasefire accord has paved the way for what could be a remarkable breakthrough in Lebanese politics.

Given the size of its base in the Shi’a community, Hezbollah is still a powerful force in Lebanon. Yet its baneful influence appears to have been greatly curtailed since its military setbacks in the war. This has given Lebanon’s new leadership a chance to gain full control of the Lebanese state and ensure that Hezbollah does not drag Lebanon into another useless and costly war with Israel.

Hezbollah, having been militarily battered by Israel, is in no position to wage war at the moment. Its charismatic and wily supreme leader, Hassan Nasrallah, was assassinated by Israel last September. His belated funeral is to take place in Beirut on February 23.

Nasrallah’s successor, Hashem Safieddine, was also killed, as were most of Hezbollah’s field commanders.

Hezbollah bases in southern Lebanon, and much of its weaponry there, have been destroyed. It would be fair to say that Hezbollah, a surrogate of Iran in the depleted Axis of Resistance, is now a shadow of its former self.

And with Assad’s downfall and Iran’s removal as a key player in Syrian politics, Hezbollah can no longer rely on Syria or Iran for logistical help in moving Iranian arms from Syria to Lebanon.

Syrian security forces on February 19 arrested smugglers who attempted to transfer weapons from Syria to Hezbollah bases in Lebanon. In recent weeks, the new Syrian government, headed by Ahmed al-Shara, has worked with the Lebanese army to interdict weapons shipments to Hezbollah.

Under pressure from Israel, Lebanese authorities have suspended inbound and outbound flights from Iran indefinitely, explaining that the Iranian regime has used civilian aircraft to smuggle cash into Lebanon to rearm Hezbollah. Lebanon banned these flights after learning from the United States that Israel might shoot down Iranian commercial airliners.

In the meantime, Israel has accused Turkey, once a regional ally, of cooperating with Iran in this apparent scheme to rearm Hezbollah.

“There is an intensified Iranian effort to smuggle money into Lebanon for Hezbollah to restore its power and status,” Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar told U.S. Middle East envoy Morgan Ortagus last week. “This effort is being carried out, through among other channels, via Turkey.”

Israel will presumably need the assistance of the United States to deter Turkey from helping Hezbollah.