Sex trafficking boomed in 19th and 20th century Argentina, and many of its participants were Jewish immigrants from the Russian empire and independent Poland. Daniel Najenson’s disturbing documentary, The Impure, which is now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform, explores this seamy and lucrative trade, which reached a seemingly unstoppable trajectory between the 1880s and the 1920s.

Several million Europeans poured into Argentina, a fast-developing nation, from the 1860s onwards. Among them were about 100,000 Russian, Polish and Ukrainian Jews, most of whom were initially males.

With the passage of time, the gender balance shifted as increasing numbers of females joined their spouses, families or boyfriends in Argentina.

Nearly 3,000 of these women were trafficked as sex workers. Most were Jewish.

The Impure, a reference to the Jewish brothel owners, pimps and prostitutes, examines this white slavery ring, which eventually spread its tentacles into neighboring Brazil and the United States.

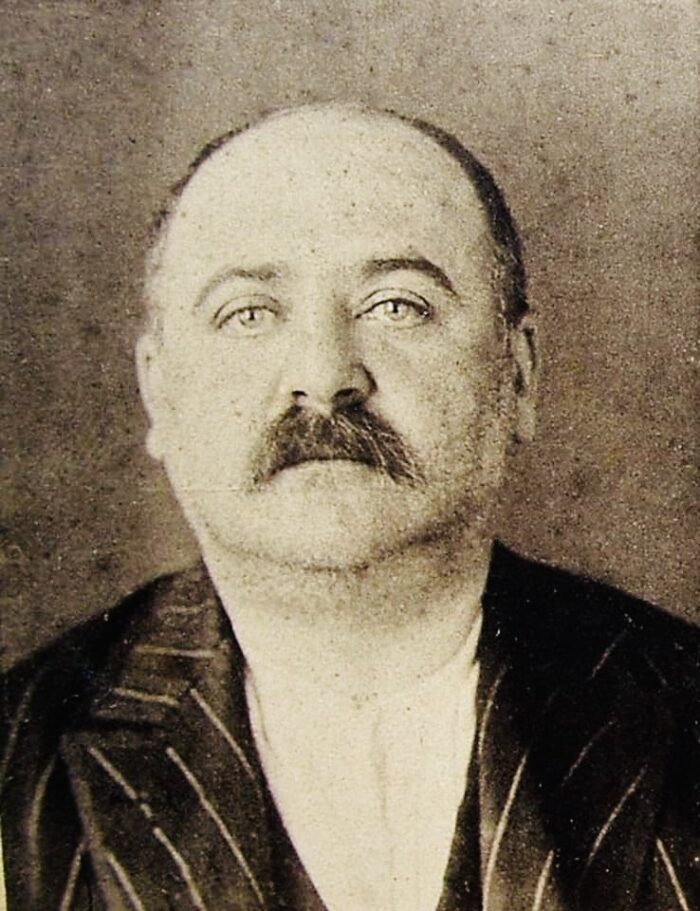

Luis Zvi Migdal, an East European Jewish criminal, was at the center of it. He was instrumental in the formation of Zvi Migdal, a tightly-run organization of brothel keepers who treated the hapless women they lured into prostitution like merchandise to be bought and sold.

Najenson mentions his name only in passing and does not delve into his dark career, leaving a yawning chasm in the film. But he does examine Migdal’s devious modus operandi. He and his shady associates, almost almost of whom had been active in the sex trade in Europe, dispatched smooth, fast-talking emissaries to Russia and Poland whose sole task was to cajole naive young women into prostitution. Tragically, they were led to believe they would be matched with husbands and/or respectable jobs once they arrived in Buenos Aires.

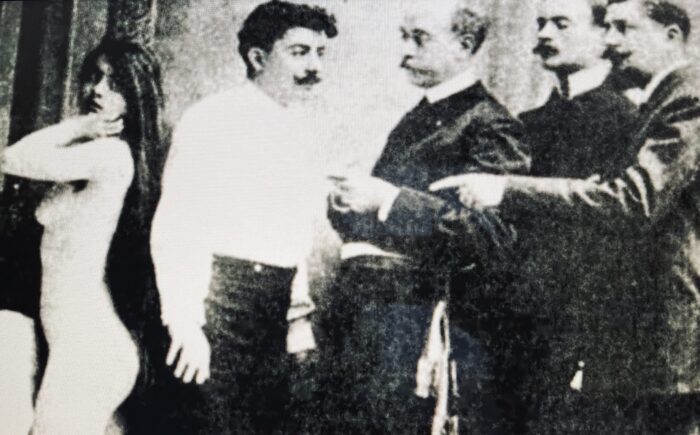

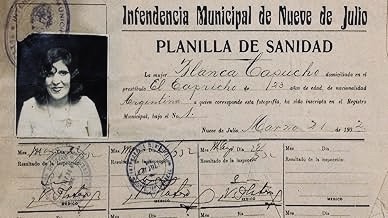

Thousands, having fallen for the ruse, were condemned to a miserable life as sex slaves in a country where prostitution had been legalized in 1875. Under this system, prostitutes were officially registered and were required to submit to regular medical examinations.

Needless to say, Jewish Argentinians were embarrassed by these criminals, many of whom were observant Jews. The Jewish community shunned them and went as far as prohibiting the “impure” from being buried in Jewish cemeteries, forcing Jewish prostitutes to build their own cemetery. Avellaneda, as it is known, is overgrown with weeds and is closed to visitors today.

Zvi Migdal thrived until about 1930, when the authorities cracked down on it after a former Jewish prostitute, Raquel Liberman, lodged a complaint with the police.

A resident of the Polish city of Lodz, she arrived in Buenos Aires with her husband and two children in 1924. Tragedy struck when her spouse suddenly died. She remarried, but her second husband, a scoundrel, forced her into prostitution. Having managed to extricate herself from the oldest profession, she went to the police chief, an apparently honest man bent on closing the city’s brothels.

Several of Zvi Migdal’s principals were deported after a trial. And following a military coup in 1930, prostitution was banned altogether.

Najenson tells this story clearly and compellingly, relying on commentaries from historians, researchers and relatives of prostitutes to fill in blanks.

Yet he leaves out a lot. He spends far too little time on the origins and operations of Zvi Migdal, particularly after the official ban on prostitution. He ignores the connection between Jewish sex traffickers and antisemitism in Argentina. He does not tell us how many Jewish prostitutes left the business after 1930.

Despite its glaring omissions, The Impure is usually a sound and absorbing account of an intriguing footnote in Jewish and Argentinian history.