Donald Trump is trying to fix what he broke.

In 2018, during his first term as U.S. president, Trump unilaterally pulled out of the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, denouncing it as a terrible deal and imposing crippling sanctions on Iran’s economy.

Last week, in an about-face,Trump dispatched a delegation to Oman to lay the ground for modifying the agreement to his specifications.

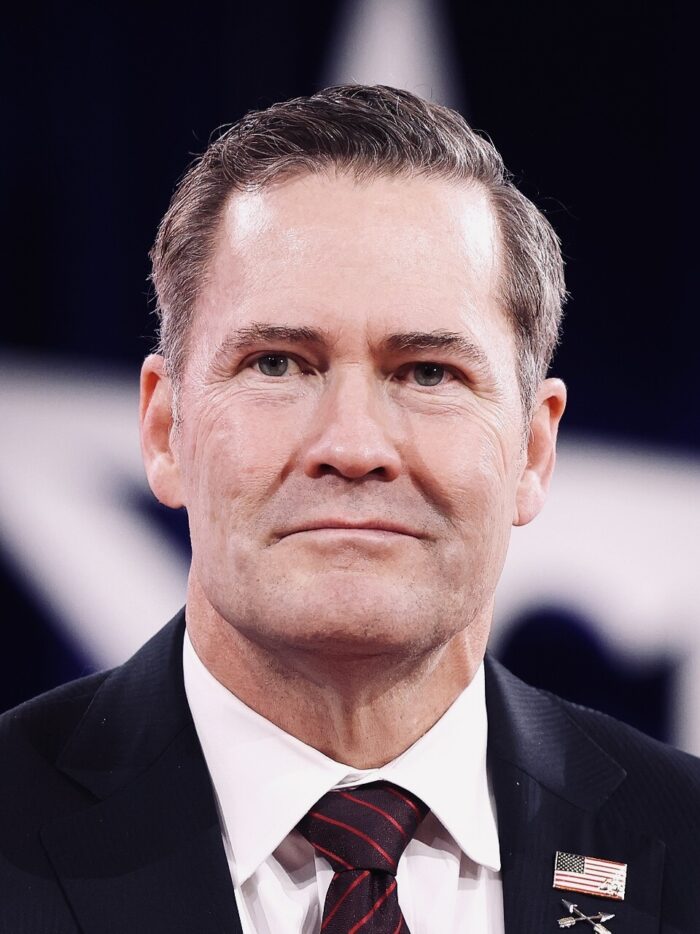

The U.S. team, led by Steve Witkoff, Trump’s special envoy to the Middle East, arrived in Oman after Trump offered to reopen negotiations over Iran’s fast-advancing nuclear program.

Two months ago, he reimposed a “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran to drive down its oil exports to practically zero.

Contrary to Trump’s preference, the talks were indirect and mediated by Oman, as per Iran’s insistence. The discussions were described by both sides as “constructive.” Witkoff and Abbas Araghchi, the Iranian foreign minister and Iran’s lead negotiator, met after the formal session and spoke for about 45 minutes.

An Iranian foreign ministry spokesman said the negotiations would continue to be indirect. A second round will take place in Oman on April 19.

Under the original accord, which took two years to negotiate, Iran broadly agreed to freeze its nuclear program in exchange for relief from sanctions. While U.S. President Barack Obama sought to prevent Iran from building a nuclear weapon, he did not demand the full dismantlement of its nuclear and missile programs, or the dissolution of its Axis of Resistance, the network of anti-American and anti-Israel proxies in the Middle East.

These yawning omissions led Trump to withdraw from the agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, and prompted Israel to denounce it.

During the previous presidency of Joe Biden, the United States and the signatories of the JCPOA — Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany — engaged Iran in sporadic and indirect negotiations to improve the accord. These talks failed.

In the meantime, Iran quadrupled its production of enriched uranium to 60 percent purity, 30 percent short of the level required to produce an atomic weapon.

“These actions by Iran are worrying,” said Rafael Grossi, the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, recently.

Iran has consistently but implausibly claimed that its nuclear program is peaceful and that it does not seek to acquire nuclear weapons.

The latest round of talks were set into motion when Trump, in a letter to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, proposed fresh negotiations. Trump expressed a preference for diplomacy over war, threatening to attack Iran if it spurned talks and warning he would not tolerate a nuclear-armed Iran.

“Iran has to get rid of the concept of a nuclear weapon,” he said in his most recent statement on April 14. “They cannot have a nuclear weapon. I want them to be a rich, great nation. The only thing is, one thing, simple, it’s really simple: They can’t have a nuclear weapon. And they’ve gotta go fast. Because they’re fairly close to having one. And they’re not going to have one.”

Having been burned by Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA, Khamenei initially rejected new negotiations with the U.S. as “unwise and unintelligent.” However, he left the door open for indirect talks, particularly after senior officials told him that the future of the Islamic regime would be thrown into doubt if he turned down negotiations.

Iran went into the talks in a weakened state. The majority of its air defence batteries were destroyed by the Israeli Air Force last October. Its surrogates, Hezbollah and Hamas, have been seriously battered by Israel in wars in Lebanon and the Gaza Strip. And Iran’s staunchest regional ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, was toppled by Islamist forces last December. This means that Iran has lost its base in Syria.

Despite these developments, Iran is expected to resist pressure to dismantle its entire nuclear infrastructure, its ballistic missile program, or its Axis of Resistance.

Witkoff told the Wall Street Journal that he was open to compromise on the dismantlement issue. “I think our position begins with dismantlement of your program. That is our position today. That doesn’t mean, by the way, that at the margin we’re not going to find other ways to find compromise between the two countries.”

Trump’s national security adviser, Mike Waltz, has adopted a harder line, having said that any deal must result in the complete dismantling of Iran’s nuclear program, including its uranium enrichment activities, weaponization efforts, and strategic missile development.

The Trump administration, in pursuit of its objectives, has applied military pressure on Iran. In recent weeks, the U.S. has sent two aircraft carrier groups to the Middle East and delivered two THAAD anti-missile defence batteries to Israel. In addition, Trump has deployed B-2 bombers relatively close to Iran. They can carry the heaviest bunker-busting bombs, which can penetrate Iran’s underground nuclear facilities.

Last month, in another demonstration of its fire power, the U.S. began striking the Houthis, an Iran-backed group in Yemen that has interfered with international shipping in the Red Sea.

Despite Trump’s bravado, Israel fears he may not demand a total shut down of Iran’s nuclear program. It would appear that his bottom line is to ensure that Iran will not enrich uranium beyond 3.6 percent rather than dismantle its nuclear program altogether.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has called for the complete dismantlement of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure along the lines of the 2003 Libyan model. As he put it recently, “The deal with Iran (would be) acceptable only if (Iran’s) nuclear sites are destroyed under U.S. supervision. Otherwise, the military option is the only choice.”

Israel’s case was lucidly outlined by David Horowitz, the editor of the Times of Israel, in a recent piece.

“The JCPOA actually legitimized Iran’s nuclear program. The deal allows Iran to retain core nuclear facilities, permits it to continue research in areas that will dramatically speed its breakout to the bomb should it choose to flout the deal, but also enables it to wait out those restrictions and proceed to become a nuclear threshold state with full international legitimacy.

“Iran was not required to disclose the previous military dimensions of its nuclear program; it was not required to halt all uranium enrichment; it was not required to dismantle its various nuclear facilities; it was not required to halt its ongoing missile development; it was not required to halt R&D on faster centrifuges to accelerate uranium enrichment; it was not required to submit to ‘anywhere, anytime’ inspections of any and all facilities suspected of engaging in rogue nuclear-related activity, and procedures were not established setting out how the international community would respond to different classes of Iranian violations to ensure that an Iranian breakout to the bomb would be prevented.”

In conclusion, he warned, “Iran is a decade further along the road not to a bomb, but to a deliverable nuclear arsenal — an Israel-threatening, world-threatening deliverable nuclear arsenal, in the hands of an ideologically and territorially rapacious regime for which Israel is only the Little Satan and the U.S. the Great Satan.”

These are compelling arguments, but it is debatable whether Trump will take these crucial considerations into mind as talks with Iran proceed.