The late Herberts Cukurs, a Nazi collaborator in German-occupied Latvia, had blood on his hands. As a commander of the Arajs Kommando, a Latvian police unit under the authority of the German occupying force, he played a critical role in the mass murder of local Jews.

Latvian historian Andrew Ezergailis, the author of The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941-1945, exposed him as a war criminal, saying that Cukurs was directly involved in the atrocities in the Riga ghetto and in the massacres in the Rumbula forest.

After World War II, Latvian Holocaust survivors living in Israel testified against him, branding him as a cold-blooded killer.

Despite his despicable wartime record, the Latvian Prosecutor General’s Office recently closed its case against Cukurs. The prosecutor, Juris Locmelis, ruled that his actions under Latvian law could not be equated with genocide.

Incredibly, this was the third time since 2019 that the case against him was dropped. On two previous occasions, the prosecutor claimed that there was insufficient evidence to link Cukurs to genocidal crimes.

In drawing its misguided conclusions, the Prosecutor General’s Office dismissed the first-hand testimony of Jewish survivors, now deceased, who saw Cukurs shooting Jews in Riga.

By any yardstick, its decision is an offensive and baffling miscarriage of justice, as well as a “perversion of the historical record,” as Pinchas Goldschmidt, the president of the Conference of European Rabbis, said.

Ilya Lensky, the director of the Jews in Latvia Museum, plans to appeal the decision, but the odds are against him.

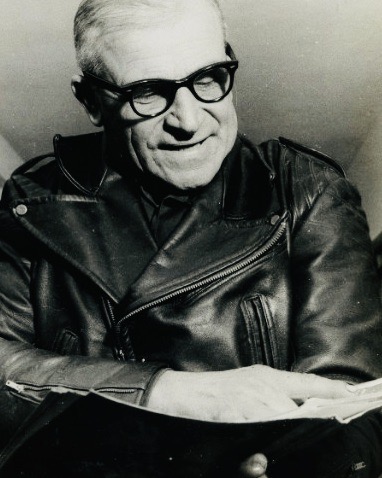

A renowned aviator before the war, Cukurs is generally regarded as a national hero in Latvia, a Baltic state which regained its independence in 1990 after half a century of Soviet domination.

Twenty years ago, a far-right political party in Latvia issued and distributed glorifying postal envelopes with Cukurs’ image. The then foreign minister, Artis Pabriks, condemned this act. “Those who produced such envelopes evidently do not understand the tragic history of World War II in Latvia or in Europe,” he said.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated unequivocally that Cukurs was “guilty of war crimes,” and that he “took part in the activities of the notorious Arajs Kommando, which participated in the Holocaust and was responsible for the killing of innocent civilians.”

In the following year, Cukurs’ admirers shamelessly mounted “Herberts Cukurs: The Presumption of Innocence,” an exhibition that the Jewish community correctly deplored as “an attempt to rehabilitate a war criminal.”

Cukurs role during the German occupation of Latvia is evident. Sensing which way the political wind was blowing, he joined the Arajs Kommando, which the post-war Nuremberg war crimes trial classified as “a criminal organization.”

Like some of his Nazi-affiliated accomplices, he escaped to South America after the war, settling in Brazil under his own name. There he portrayed himself as both a political exile who had been persecuted by the communists and a savior who had rescued Jews during the Holocaust.

Astonishingly enough, he cynically referred to himself as “the epitome of humanity” in an interview with a mass-circulation Brazilian magazine.

Ultimately, his unsavory past caught up with him. But efforts by the Jewish community to have him extradited to Latvia faltered in the face of official indifference. By then, he was earning a living as an operator of a boat rental and air taxi business near Sao Paulo.

The Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, set its sights on him. In 1965, he was assassinated by one of its hit teams, which left documents on his corpse attesting to his war crimes.

All the evidence points to Cukurs’ guilt. When will the Latvian Prosecutor General’s Office finally recognize this fact?

Its failure to do so is proof of its reluctance to come to terms with one of the blackest chapters in Latvia’s history.