The deadly attack launched by Hamas in Israel on October 7, 2023 was not only the latest chapter in Israel’s decades-long struggle with the Palestinians. It was also a sign of Iran’s ascendancy as a major power in the Middle East and an illustration of the Axis of Resistance alliance it had formed to harass and hurt Israel by a “ring of fire.”

Hamas’ bloody invasion was inextricably linked with a strategy that Iran had honed to defeat Israel and defy the United States, Israel’s chief ally. As a member of Iran’s political and military alliance, Hamas shared its twin objectives.

Israel responded ferociously, determined to destroy Hamas and curtail Iran’s influence in the region.

According to Vali Nasr, the author of Iran’s Grand Strategy: A Political History, published by Princeton University Press before the outbreak of Israel’s current war with Iran, the West was “surprised by the capabilities of the axis, and was clearly unaware of its intent and plan of action.”

The West’s understanding of Iran’s calculations, he notes, was and is “hopelessly inadequate and dangerously outdated.”

Nasr, a professor of international affairs and Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins University, argues that the West still looks at Iran through the prism of the 1979 Islamic revolution and the central role that Islam and the clergy played in it. While these theocratic underpinnings remain important and are embedded in Iran’s statecraft, the values of the revolution do not entirely explain Iran’s actions abroad.

In other words, the policies that Iran pursued during the Israel-Hamas war cannot be explained solely by Islamic ideology or Iran’s desire to export its revolution, he states.

“The war in Gaza made it clear that Iran today sees itself as the inspiration for a global movement of resistance to the United States — a reinvocation of the familiar anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism of the latter part of the twentieth century — and seeks to organize the Middle East around it.”

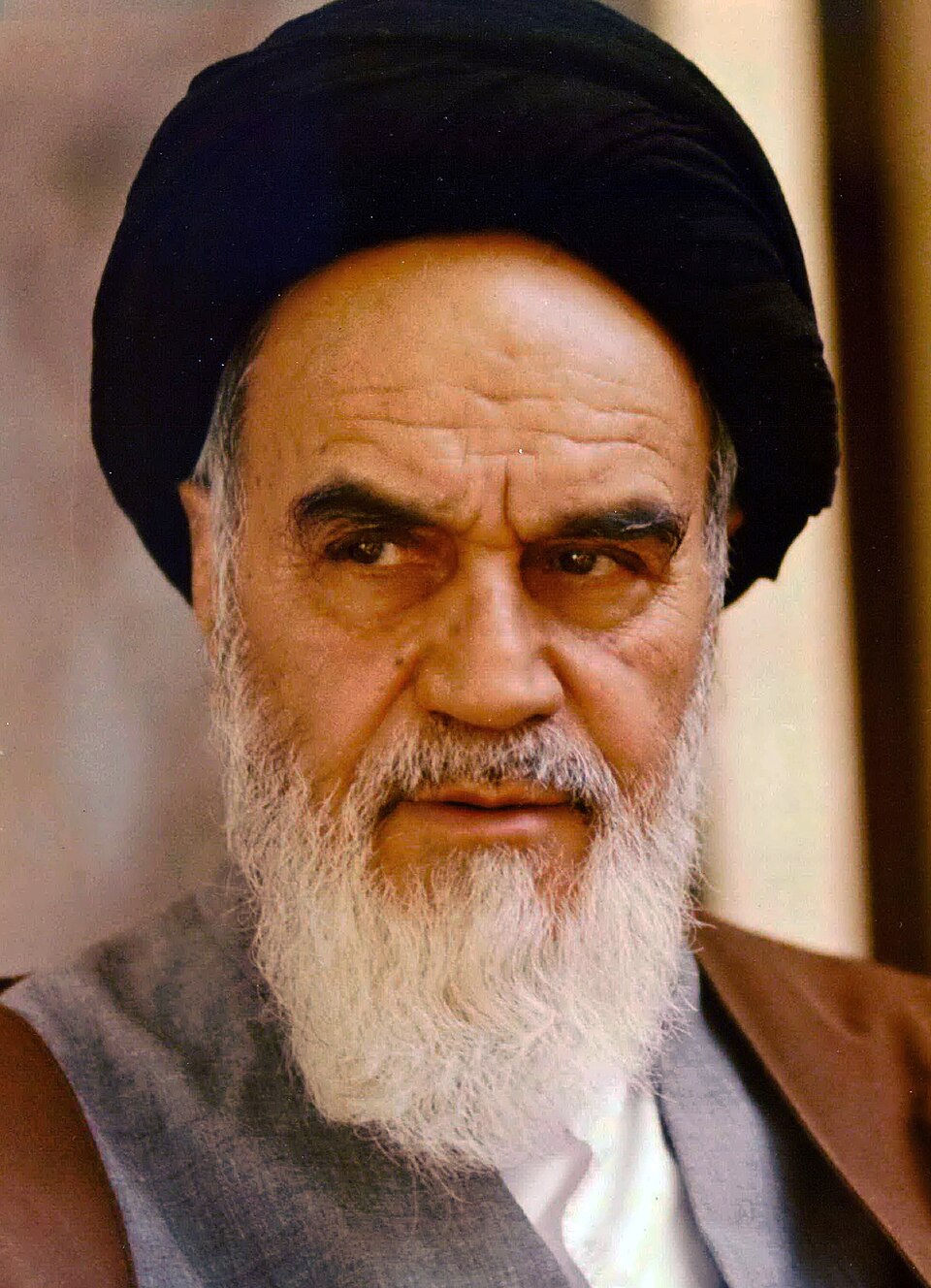

According to Nasr, Iran’s goals are now “secular in nature,” attached to a vision of national security that was broadly defined by two of its supreme leaders, the ayatollahs Ruhollah Khomeini and Ali Khamenei. This grand strategy guides Iran today and is designed to ensure its security and compel the United States to abandon its containment policy of Iran. These concerns shape the assumptions, logic and intent of Iran’s strategy.

Iran’s nuclear program, as well as its strategy of “forward defence,” the doctrine of defending Iran through the extension of its influence in the Arab world, are both expressions of its aspirations as a nation.

By Nasr’s reckoning, Iran’s policy is based on bitter historical experiences. Two catastrophic wars with Russia in the nineteenth century, plus British and Russian occupations and American meddling in the twentieth century, have had a lasting effect. As a result, Iran fears foreign interference, loss of sovereignty, chaos and disintegration.

Nasr examines these issues in voluminous detail, delves into the origins and outcome of the 1979 revolution, and analyzes Iran’s contentious relationship with Israel, its main regional foe.

Iran’s perception of Israel has been mercurial.

While Mohammed Reza Shah, the pro-western monarch, regarded Israel as a useful ally in confronting Arab radical nationalism, his Islamic successors viewed Israel through the lens of the Palestinians. Khomeini believed that Israel was a colonial threat and that its very existence was inimical to Iran’s interests.

During the Iran-Iraq War, when Iran was mostly in retreat, Khomeini dispatched forces to Lebanon. Israel had just invaded southern Lebanon, whose predominately Shi’a Muslim population had close religious connections to Iran. From this point forward, Iran committed itself to confronting Israel.

There was, nonetheless, a logical convergence of interests between Iran and Israel at this juncture. Since neither Israel nor the United States wanted Iraq’s president, Saddam Hussein, to emerge victorious from the war, which lasted from 1980 until 1988, Israel agreed to supply Iran with spare parts for its U.S.-made military equipment. Khomeini approved the unusual arrangement on the condition that it remained secret. Iran, too, provided Israel with the intelligence that it needed to bomb Iraq’s nuclear facility near Baghdad in 1981.

Israel’s detente with Iran was, of course, temporary. In 2003, Iran formally embraced the concept of “forward defence,” which relied on the deployment of Shi’a militias trained by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.

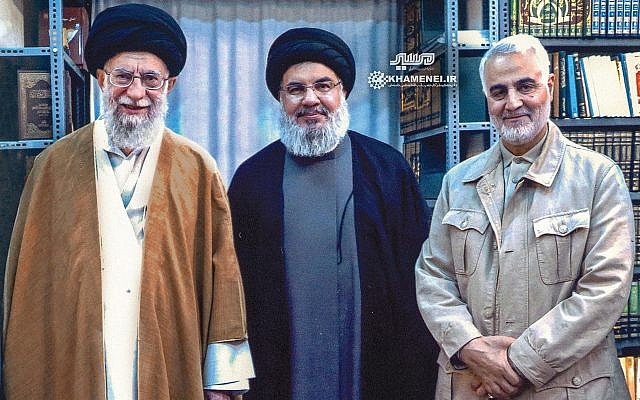

These militias were part of the Axis of Resistance, the brainchild of Hezbollah but the operational baby of Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, an arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps. As Nasr observes, the Quds Force would dominate Iran’s military and political presence in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen.

While Iran regards “forward defence” as a means by which to protect itself, Arab states and Israel regard it as expansionist and aggressive in nature, aimed at securing Iran’s regional hegemony. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in a speech to the U.S. Congress, warned that Iran dominated four Arab capitals: Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus and Sanaa.

Inevitably, Iran’s “forward defence” strategy elicited a backlash, pushing the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco to normalize relations with Israel under the 2020 Abraham Accords.

This was a major blow to Tehran, but Iran remained undaunted. It pursued its strategy relentlessly, particularly in Syria, a vital link to Lebanon and Hezbollah. With the fall of Saddam Hussein, following the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the Iranian regime attempted to create a land corridor from Iran to Lebanon. Israel regarded it as a threat and reacted accordingly.

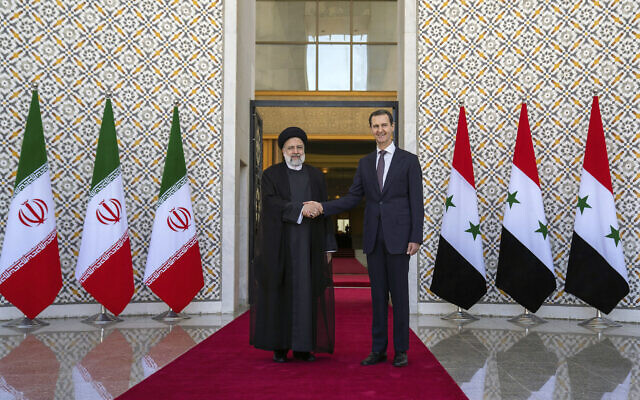

With the eruption of the civil war in Syria in 2011, Iran rallied behind Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, fearing that his demise would imperil its “forward defence” strategy. In defending Assad from Syrian rebels and the Islamic State organization, the Quds Force recruited Lebanese, Iraqi, Afghan and Pakistani Shi’a mercenaries.

Beyond protecting Assad, Iran used Syrian territory as a platform from which to attack Israel. In response, Israel bombed Iranian and Syrian military sites in Syria on a regular basis from 2013 onward.

In Nasr’s estimation, the current war in Gaza was a turning point for “forward defence,” a display of Iran’s “reach and effectiveness” in projecting regional influence. After October 7, however, Israel dedicated itself to obliterating two of Iran’s proxies, Hamas and Hezbollah.

Last April and October, Israel and Iran clashed in four direct confrontations, the first armed engagements of their kind. And since last week, Israel has been intent on eradicating Iran’s nuclear program and its stocks of ballistic missiles.

Nasr contends that Iran’s strategy has alienated Iranians who think it has invited crippling U.S. economic sanctions. “Iranians have come to question the wisdom of resistance, and increasingly voiced their opposition to forward defence,” he writes.

Nasr deals exhaustively with Iran’s nuclear program, an issue that dominates its relations with the West and shapes its politics. The program started during the Pahlavi era and was intended for civilian use, but has since been weaponized by the Islamic regime.

During Donald Trump’s first term of office, the United States imposed a regimen of “maximum pressure” on Iran. It worked. Iran’s economy and per capita income contracted by 7.3 and 14 percent.

Prior to the current war, Israel attempted to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program through cyberattacks on nuclear facilities and the assassination of Iranian scientists. Iran has rebuilt damaged sites and further accelerated its program.

Today, Israel is Iran’s primary regional adversary, with Iran regarding Israel as a U.S. proxy. As Nasr puts it, “Iran’s enmity toward Israel is no longer limited to the Palestinian issue but reflects a fundamental shift in outlook. The principal threat to Iran from the region comes no longer from the Arab world but from Israel, and it stems from Israel’s desire to be the sole power in the Middle East.”

This is an oversimplification, of course. Nasr fails to recognize the obvious: Israel’s actions are reactive and are mainly motivated by Iran’s sincere and blood curdling declarations to wipe Israel off the map. As he knows, Israel had no objection to Iran’s nuclear program before 1979.

Despite his occasional anti-Israel bias, Nasr has written a comprehensive, measured and first-rate account of modern Iran. Now that Israel and Iran are at war, it will be all the more useful.