Warsaw was virtually a Jewish city before World War II, with Jews accounting for about one-third of its population. The Nazi occupation of Poland left Warsaw in ruins and all but decimated its Jewish community, but a traveller who visits Warsaw today will find landmarks of the past and buildings attesting to the modest revival of Jewish life in contemporary Poland.

The fate of Polish Jewry was sealed on Sept. 1, 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in a blitzkrieg that overwhelmed Poland’s army. From almost the first moment of Germany’s occupation, the Nazis mistreated Jews, imposing onerous and humiliating restrictions on their lives. In 1940, they were herded into a ghetto, where hunger and disease were rampant.

In July 1942, Adam Czerniakow, the ghetto’s Nazi-appointed “elder,” was informed that its ragged inhabitants would be “resettled.” Realizing that “resettlement” was a code word for murder in Nazi extermination camps, he refused to cooperate and committed suicide in a desperate act of despair.

Nonetheless, the Germans pressed on with their diabolical plan to eradicate the ghetto, whose Jewish population represented about 10 percent of Poland’s 3.3 million Jews. On July 23, they began to remove Jews from the ghetto, a process that ended two months later. All in all, 265,000 Jews were deported to, and murdered in, the Treblinka death camp.

The following spring, the Nazis launched another round of deportations to clear the ghetto. The remaining Jews resisted in what would be the Warsaw ghetto uprising. The legendary insurrection broke out on April 19. Vastly outgunned, the Jewish fighters were summarily crushed by a well-equipped German force commanded by SS general Jurgen Stroop, who was hanged after the war.

On May 8, German soldiers discovered the Jewish partisans’ main command post at Mila 18 Street. During the ensuing battle, one of the Jewish commanders, Mordechaj Anielewicz, was killed. Thirteen thousand Jewish fighters were killed during the heroic but futile revolt. The last remaining 50,000 Jews in the ghetto were dispatched to Nazi concentration camps in Poland.

These horrific events are commemorated at an assortment of sites in Warsaw, the Polish capital.

The collection point in the Muranow district, where Jews were brought to be deported to Treblinka, is marked by a grey monument in the shape of an open freight carriage. The names of some of the deportees are etched on it. This monument, erected in 1987, was designed by the architect Hanna Szmalenberg and the sculptor Wladyslaw Klamerus.

The bunker at Mila 18, which inspired Leon Uris’ eponymous novel, is marked by a simple stone monument in a sea of drab apartment buildings.

The Nazis built a wall of red bricks around the ghetto, and the last standing section of this ugly and demeaning barrier can be seen on Zlota Street. In other places, sidewalk markers signify the location of the infamous wall.

The foot bridge on Chlodna Street, which connected the so-called small ghetto with the big ghetto, is long gone. But Natan Rappaport’s bronze and granite memorial to the ghetto fighters looms large in a square named after Anielewicz.

Ironically enough, the materials used for the construction of the memorial were originally ordered by Adolf Hitler for a monument he intended to build to flaunt Germany’s victories in World War II.

Rappaport’s memorial figured prominently in Germany’s postwar rehabilitation. In 1970, at the height of the Cold war, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt spontaneously knelt on the steps of the memorial in a spectacular gesture of contrition for Germany’s central role in the Holocaust.

Adjacent to the memorial is the new Museum of the History of Polish Jews, which opened last year and which I have yet to visit. According to reports, it’s a magnificent repository of the 1,000-year Jewish presence in Poland.

Closer to downtown Warsaw is a statue that honors the memory of Janusz Korczak, the director of a Jewish orphanage who knowingly went to his death so as not to be separated from his boys and girls.

The Nozyk synagogue, on Twarada Street, was the sole Jewish house of prayer in Warsaw to survive the Nazi era. Used by the Germans as a stable and depot, it was damaged during the 1944 general uprising. Reopened after World War II, it was twice restored, first in 1977 and then in 1983, the 50th anniversary of the ghetto revolt.

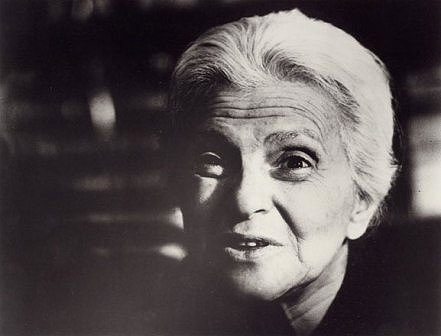

The Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street, one of the biggest in Europe, is set on 33 hectares of land and contains some 250,000 headstones. Among those interred here are the writer I.L. Pertez and the actress Esther Kaminska.

The Jewish Historical Institute, the most important academic-level Jewish institution in contemporary Poland, is a research center with archives and permanent exhibitions of Polish Jewish history and the Holocaust.

The Great Synagogue, one of Warsaw’s finest shuls, once stood adjacent to the institute, but after the ghetto uprising, the Nazis tore it down in a brutal act of vengeance. A bland bank tower stands in its place today.

Although the Nazis managed to obliterate much of Jewish Warsaw, remnants of its past are scattered around the city, reminding visitors that Warsaw was once a special place in the hearts and minds of Polish Jews.