He was the master of the brush — a painter of light.

He was Joseph Turner (1775-1851), the British landscape artist whose moody oils, watercolours and drawings guaranteed him a place of immortality in the pantheon of great European painters.

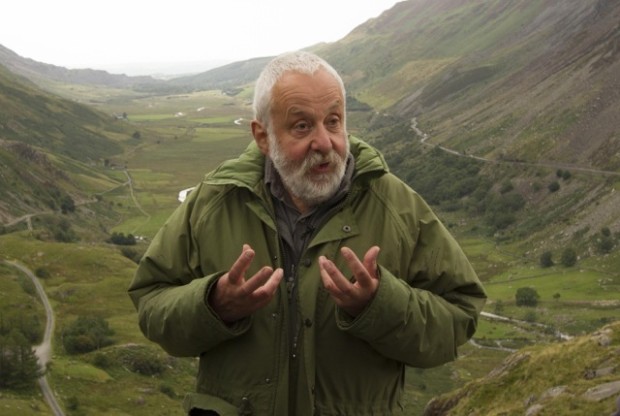

Mike Leigh’s biopic, Mr. Turner, which opens in Toronto on Dec. 25, covers the last 25 years of his life. Timothy Spall portrays Turner in a virtuoso performance, but regrettably, the film seems incomplete.

With his scrunched-up face, dishevelled figure and gruff, restless personality, Spall is a truly figure to behold. Utterly devoted to his craft, the artist he depicts lives with his father, whom he dearly loves and who is probably the only person to whom Turner is genuinely attached. Indeed, he affectionately calls him “daddy.”

No social animal, he’s estranged from his former mistress (Ruth Sheen), who mocks him at every opportunity. And he doesn’t much care for his two born-out-of-wedlock daughters, who seem distant. He’s rather formal with his house maid (Dorothy Atkinson), except when he sexually assaults her in a brutish moment of lust, which, incidentally, she appears to enjoy.

Turner, usually morose and exceedingly preoccupied, is a man in motion, constantly on the move in search of new material. In the first scene of the movie, he sketches a windmill in Holland at dusk. As the film progresses, he goes to Margate, a quaint sea-side town in Britain where he meets an attractive and intelligent widow (Marion Bailey) who will become his companion and caregiver.

Mr. Turner, a refined period piece which successfully evokes the first decades of 19th century Britain in terms of locales, clothes, manners and spoken accents, consists of artfully-staged vignettes.

Turner pays a compliment to a genteel woman giving a piano recital in a drawing room. He loans money to an artist of questionable talent and distinction who can barely support his wife and five children. He visits a bordello, whipping out his pad to draw a picture of a young prostitute. He socializes with fellow painters at an exhibit, slightly disfiguring one of his seascapes in order to rebuke one of his rivals. He rejects a generous offer from an industrialist to buy all his works, explaining that they belong to the “British nation.”

As Turner, the creator of masterpieces still valued and appreciated after more than a century and a half after his death, Spall is a marvel. He is, by turns, morose, friendly, lively and sickly, a volcanic force of nature.

The film itself is vintage Leigh. It’s unassuming in scope and style, yet it gradually grows on you, building a self-sustaining universe you’ll not easily forget. But Leigh, who wrote and directed it, should have paid a lot more attention to Turner’s evolution as a painter.

Mr. Turner emphasizes character development and the social niceties of a society, but scarcely spends any time on Turner the artist, and this is a pity and a failing.