By re-establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba after an almost 54-year break, U.S. President Barack Obama will be putting an end to a policy that long ago became pointless.

Cuba may be no democracy, but Washington enjoys diplomatic relations with at least 20 countries whose regimes are more repressive than that of the Castro brothers. Yet Cuba remained one of just a few nations, along with Iran and North Korea, that had no diplomatic relations with Washington.

The economic and political embargo against Cuba had become hostage to the domestic politics within South Florida’s Cuban community. Also, there was Washington’s petulance with an island, just 145 kilometers south of Key West, that had tweaked America’s nose during the Cold War. But, really, all that is history. With communism a spent force, Cuba long ago ceased to be a danger in the western hemisphere. In the 21st century, the United States has far more important enemies to worry about.

This announcement is long past due.

“These 50 years have shown that isolation has not worked,” Obama said in remarks from the White House on Dec. 18. “It’s time for a new approach.” The deal will “begin a new chapter among the nations of the Americas” and move beyond a “rigid policy that is rooted in events that took place before most of us were born.”

Obama has instructed Secretary of State John Kerry to begin the process of removing Cuba from the list of states that sponsor terrorism and announced that he would attend the regional Summit of the Americas in Panama next spring at which Cuban President Raul Castro is also scheduled to appear.

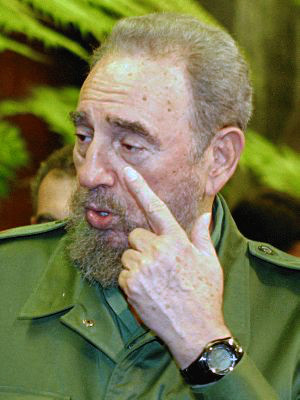

For his part, Castro stated that while the two countries still have profound differences in areas such as human rights and foreign policy, they must learn to live together “in a civilized manner.” He did add that “the economic, commercial and financial blockade, which causes enormous human and economic damages to our country, must cease.”

Since replacing his brother, Fidel, Raul Castro has allowed greater access to cell phones and the Internet, and lifted some restrictions on travel. The political system is also more open — though no competing political parties are permitted, non-communists now sit in the country’s parliament.

Tourism is now big business in Cuba, and the country is packed with Europeans and Canadians. Cubans can now open their own restaurants and hire non-family members to work in them. They are now permitted to lease land from the government in order to grow food and raise animals for the tourist hotels and restaurants. Those leasing the land can hire help to assist in their work.

The re-establishment of diplomatic ties was accompanied by Cuba’s release of American Alan Gross, who had been imprisoned for five years, and the swap of a Cuban who had spied for the U.S. for three Cubans jailed in Florida.

Gross was detained in December 2009, during his fifth trip to Cuba, and sentenced to 15 years in a Cuban prison for trying to deliver satellite telephone equipment while working as a subcontractor for the U.S. Agency for International Development. He was charged with attempting to bring down Cuba’s revolutionary system.

Gross was also involved with Cuba’s small Jewish community, setting up Internet access that would bypass local censorship and help connect Cuban Jews to the outside world.

“He’s back where he belongs, in America with his family, home for Hanukkah,” Obama said, as Gross was flown back to his home outside Washington.

Most Jews left Cuba after the 1959 revolution, and only about 2,000 remain. There are seven synagogues in the country, one Orthodox, and six Conservative. The one Reform temple has closed. The community maintains that antisemitism is rare.

Also, though Cuba does not subsidize the Jewish community, the government provides it with some income by renting space in underused buildings.

Dina Siegel Vann, the director of the American Jewish Committee’s Belfer Institute for Latino and Latin American Affairs, said Gross’ release, along with the improvement in American-Cuban relations, will allow Cuban Jews to “have stronger ties to Jewish organizations, they will be much more in the open.”

On the other hand, Cuba has long been critical of Israel, and the two countries have no diplomatic relations. After the 1967 Six Day War, Cuba condemned Israel at the United Nations. Its ambassador, Ricardo Alarcon, called the war an “armed aggression against the Arab peoples.”

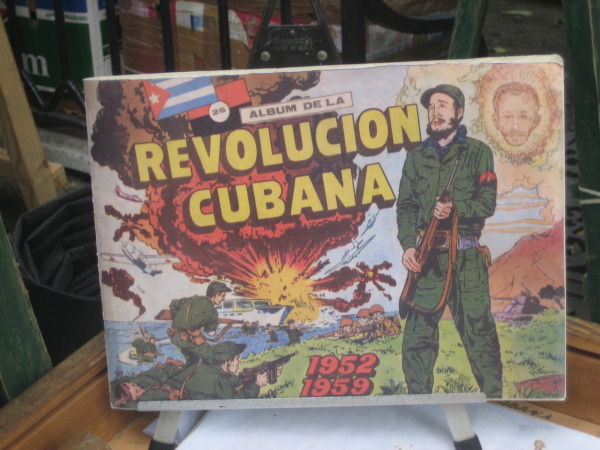

At the 1973 Conference of Non-Aligned Nations in Algiers, Castro announced that Arab arguments had convinced him to sever relations with Israel. In 1975, Cuba was one of only three non-Arab governments to sponsor the resolution declaring “Zionism is Racism” that was adopted by the UN General Assembly.

Although Israel’s then chief Ashkenazic Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau visited Cuba and was cordially received by Fidel Castro in 1994, this hostility remains unabated. During last summer’s war in the Gaza Strip, Cuba accused Israel of using its military and technological superiority to execute a policy of collective punishment causing the death of innocent civilians and huge material damage.

Fidel Castro, in an Aug 5, 2014 article titled “Palestinian Holocaust in Gaza,” published in the Communist newspaper Granma, referred to “the genocide of Palestinians,” and described Israel’s offensive in Gaza as a “new, repugnant form of fascism.”

Clearly, relations between Havana and Jerusalem are not on the horizon.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.