The Sunni jihadist organization Islamic State appears to have lost some of its momentum.

It has not made any meaningful territorial gains in Iraq since last year, when it threatened Baghdad, the capital, and captured Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, in a lightning offensive that reverberated across the Middle East.

More to the point, Islamic State has lost about 700 square kilometres of territory in the past few months, according to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

Late last month, Kurdish pesh merga forces aligned with the Iraqi government recaptured the Syrian town of Kobani after a fierce four-month battle, handing Islamic State a major defeat. And a few days ago, Islamic State was dealt another blow when it failed to take a key military base in western Iraq, where some 400 U.S. and allied personnel are currently training Iraqi forces for a spring offensive against the jihadists.

By Kerry’s estimate, Islamic Jihad is being squeezed by allied bombing raids that have exacted a fearsome toll. Since last August, the United States and its European, Canadian and Arab allies have carried out more than 2,000 bombing raids in Iraq and Syria, killing thousands of Islamic State fighters.

Kerry’s upbeat assessment is shared by a bitter rival, General Qassem Suleimani, the commander of Iran’s Quds Force, which has helped Shiite forces in Iraq stem the tide of Islamic State advances. In a reference to Islamic State and other unspecified groups, he declared, “We are certain these groups are nearing the end of their lives.”

Despite these optimistic forecasts, Islamic State — which is dedicated to establishing a borderless religious state in the Middle East governed by the austere strictures of Sharia law — still holds immense swaths of land in Iraq and Syria, and is expanding its sphere of influence in Egypt, Libya, Lebanon, Jordan, Yemen and Algeria.

And as Kerry has pointed out, difficult challenges lie ahead. In addition to defeating Islamic State on the battlefield, which will be no easy task, the international coalition of 60 nations arrayed against Islamic State must stop flow of foreign recruits into its ranks, curb its fund-raising drive and discredit its radical ideology.

The battle against Islamic State is being waged as Muslim extremists in Europe look to Islamic State for inspiration and guidance. In the past year, they’ve launched terrorist assaults in France, Belgium and Denmark, all of which raise pertinent questions about the integration of Muslims in European societies, the wisdom of Europe’s immigration policies and the safety of Jewish communities in Europe.

As Europeans ponder these stark and unavoidable issues, Islamic State continues to murder foreign hostages — mostly aid workers and journalists — in ghoulish spectacles that horrify public opinion in the West and the Arab world.

In one of the most graphic incidents of its kind, Muaz Kasasbeh, a Jordanian pilot, was burned alive in a cage after being shot down over Syria last December in a bombing raid. His murder stirred red-hot rage in Jordan and prompted King Abdullah II to order retaliatory air strikes against Islamic State weapon depots, training centers and military barracks.

During one of these raids, Kayla Mueller — a 26-year-old American hostage whom Islamic State had held since 2013 — may have been killed. Jordan claims that Mueller was murdered before the bombings.

Whatever the case may be, their deaths have further blackened Islamic State’s reputation and emboldened Arab states, Iran and the United States to adopt a tougher approach toward the jihadists

Reacting to the pilot’s demise, the Egyptian government and its nemesis, the Muslim Brotherhood, both denounced Islamic State. And the head of Cairo’s prestigious Al Azhar institute, Grand Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayeh, called for revenge. Islamic State combatants, he said, should be “killed, crucified, or their hands and legs cut off.” On Feb. 15, Egypt’s air force struck arms depots and training camps of Islamic State’s affiliate in Libya after more than a dozen Egyptian Copts were beheaded.

Further afield, the Iranian government described Kasasbeh’s killing as “inhumane and un-Islamic,” and Al Manar, the television mouthpiece of Hezbollah, called it “the most gruesome” of atrocities committed by Islamic State.

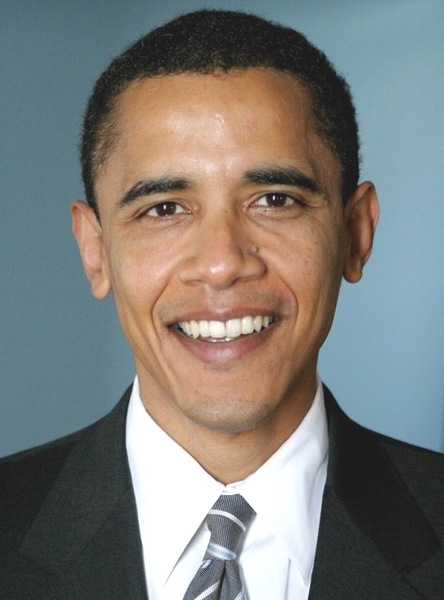

On Feb. 11, President Barack Obama — a presidential candidate who promised to withdraw U.S. forces from the Middle East — formally asked Congress to authorize a three-year campaign of limited ground operations against Islamic State. “If left unchecked,” he said, Islamic State “will pose a threat beyond the Middle East, including the United States homeland.”

Under the proposed legislation, U.S. special forces would assist front-line Arab countries like Iraq to resist Islamic State, while American air strikes would continue apace.

Obama’s decision to send yet more troops to the Middle East comes nearly five months after he acknowledged that the United States had underestimated the rise of Islamic State and had overestimated the will and ability of the usually inefficient Iraqi army to perform adequately.

The latest developments signify that Obama finally understands that air power alone will not push back Islamic State, a nimble and adaptable adversary.

Obama’s volte face is not all that surprising. Last September, the chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, told the Senate Armed Services Committee that the deployment of ground troops would be necessary if air strikes proved to be insufficient.

One can safely assume that a fresh infusion of American troops will be sent to Iraq rather than Syria. The United States has a working relationship with the Shiite-dominated Iraqi government, which has close ties with Iran. By contrast, Washington is hostile to and at odds with the Iranian-backed Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

Last November, Obama categorically ruled out an alliance with Syria, saying that Assad has “completely lost legitimacy with the majority of the country” due to the four-year-old civil war, which has laid waste to Syrian cities and claimed the lives of more than 200,000 Syrians.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration has dismissed speculation that the United States and Iran are tacitly working together in opposition to Islamic State, a common enemy. Last November, however, Obama wrote a letter to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Khameini, suggesting that U.S.-Iranian cooperation in the Middle East could be possible should an agreement on Iran’s nuclear program be signed.

If Islamic State is to be contained, if not vanquished, there will need to be real political reconciliation between Sunnis and Shiites in Iraq. Iraq’s former prime minister, Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, fomented sectarian strife and thereby left an opening for Islamic State to exploit.

Maliki’s U.S.-supported successor, Haider al-Abadi, is far more conciliatory, but he can only forge communal unity in Iraq if he succeeds in overhauling the security services and making them much more representative of Iraq’s diverse population of Sunnis, Shiites, Kurds and Christians.

It’s probably fair to say that, as long as Shiites and Sunnis remain at loggerheads, Islamic State will be the sole beneficiary.

The situation in Syria is far more complicated and murkier, since the United States is seriously estranged from the Syrian government. As a result, the chances that American ground forces will be placed in Syria to fight alongside the Syrian armed forces are nil at present.

Since the Syrian army and its ally, Hezbollah, will be hard-pressed to subdue Islamic State without the active military assistance of a major power like the United States, the war against Islamic State is likely to drag on indefinitely, with all its attendant consequences.